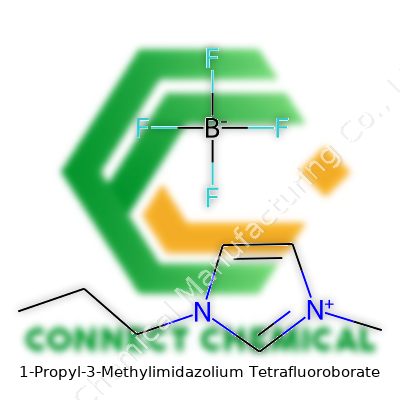

1-Propyl-3-Methylimidazolium Tetrafluoroborate: An In-Depth Exploration

Historical Development

Interest in ionic liquids drifted into mainstream chemistry in the closing decades of the twentieth century. Before synthetic chemists started exploring 1-propyl-3-methylimidazolium tetrafluoroborate, traditional solvents had already raised questions about safety, volatility, and waste. Trade-offs around cost and scale made many labs hesitant to ditch solvents like chloroform and ether for something unfamiliar. Yet as the search for “green chemistry” solutions intensified and regulations tightened, researchers gave more attention to imidazolium-based compounds. Early studies, drawing from work in the 1980s and 1990s, built on findings on room-temperature molten salts. As a result, this compound gained traction among chemists because of its low vapor pressure, thermal stability, and ability to dissolve a wide variety of organic and inorganic materials. Practical uses did not end with academic curiosity—petrochemical engineers, battery designers, and even pharmaceutical scientists got involved. By the early 2000s, custom-made ionic liquids had become available from both specialty chemical producers and global chemical suppliers, with 1-propyl-3-methylimidazolium tetrafluoroborate taking a lead role.

Product Overview

1-Propyl-3-methylimidazolium tetrafluoroborate belongs to the class of ionic liquids that refuse to fit the old-world notion of solvents. Built from the marriage of an imidazolium cation and a tetrafluoroborate anion, it emerges as a clear, colorless to pale yellow liquid at room temperature. Its low melting point and ability to remain liquid well below 100°C set it apart from many traditional salts. The compound shows almost no detectable odor. Many suppliers standardize their product for use in both research and some industrial processing, although lab-grade bottles remain the most common encounter for most scientists and engineers. Occasionally, you encounter the compound under abbreviations like [PMIM][BF4], showing its systematic side. Larger-scale commercial containers, properly sealed, can preserve the ionic liquid's purity for an extended shelf life, as long as they’re kept away from sources of moisture.

Physical & Chemical Properties

The physical properties of 1-propyl-3-methylimidazolium tetrafluoroborate make it stand out in the search for alternatives to volatile organic solvents. Its density ranges between 1.18 and 1.25 g/cm3 at room temperature, packing more mass into a smaller volume than water. Pure samples resist evaporation due to an extremely low vapor pressure. The viscosity, though higher than many common organic solvents, rarely hinders mixing or processing unless working at temperatures well below ambient. This compound’s miscibility with water shifts from partial to substantial based on the batch and purity—a detail anyone developing new applications soon learns to respect. On the chemical side, thermal stability holds up to roughly 300°C, a temperature where many traditional liquid solvents would break down or boil away. The ionic liquid lets few impurities slip by, but anyone handling it knows to watch for hydrolysis or slow degradation of the tetrafluoroborate anion under acidic or moist conditions, which can release toxic byproducts like hydrogen fluoride. Good laboratory technique requires some respect for these subtleties to avoid nasty surprises.

Technical Specifications & Labeling

Suppliers typically label 1-propyl-3-methylimidazolium tetrafluoroborate with purity grades ranging from 95% up to 99.5% or higher for electronic and research use. Bottles come with hazard symbols related to chemical handling—corrosive to skin and eyes, potential acute toxicity if ingested, and environmental harm in the case of improper disposal. The label includes the chemical formula C7H15BF4N2, CAS number 174501-65-6, and recommends storage in tightly capped, moisture-free conditions above freezing point but below 40°C. Smart buyers look for certificates of analysis that verify properties such as water content, residual acids, organic impurities, and the absence of major metal contaminants, all of which impact experimental reproducibility and technical results in applied research.

Preparation Method

Synthesizing 1-propyl-3-methylimidazolium tetrafluoroborate rests on the alkylation of 1-methylimidazole with 1-bromopropane to generate the [PMIM]Br salt, followed by anion exchange with sodium tetrafluoroborate. The process involves shaking or stirring the organic and aqueous phases, removing the aqueous layer, and washing the product repeatedly with deionized water. Careful drying under high vacuum eliminates traces of water and volatiles. Chemists often distill the solvent to further purify the final product, paying close attention to the dangers posed by residual halides or incompletely exchanged anions. Over the years, methods have become more reliable, with safer alternatives to sodium tetrafluoroborate being developed, although the classical route has stood the test of time due to its efficiency and cost-effectiveness. Lab workers find value in using strictly anhydrous conditions and inert atmospheres to minimize decomposition or unwanted side reactions.

Chemical Reactions & Modifications

The imidazolium core stands out for its resilience during both organic and inorganic transformations. In practice, the cation rarely takes a hit under standard reaction conditions, although strong bases may deprotonate the ring, and nucleophilic agents could potentially disrupt the alkyl chains. The anion, tetrafluoroborate, shows vulnerability to hydrolysis, yielding boron trifluoride and hydrogen fluoride if exposed long enough to water and acids—a safety note for anyone scaling up. Chemists often modify the alkyl chains or swap the tetrafluoroborate for other anions like bis(trifluoromethylsulfonyl)imide to tune properties such as hydrophobicity, viscosity, and solvation power. This versatility opens doors for those engineering new reactions or searching for improved electrolyte formulations.

Synonyms & Product Names

Across chemical catalogs and research publications, you find several synonyms for 1-propyl-3-methylimidazolium tetrafluoroborate, which can be confusing for the uninitiated. The official IUPAC name appears as 1-propyl-3-methyl-1H-imidazol-3-ium tetrafluoroborate, but suppliers frequently shorten it to [PMIM][BF4] or PMIM-BF4. Other variations, like 1-n-propyl-3-methylimidazolium tetrafluoroborate, reflect minute differences in chain structure that draw concern only in the rarest cases. The marketplace has adopted these short labels for ease, but it helps to cross-reference with CAS numbers to avoid miscommunication or mix-ups, especially with shipment labels that travel worldwide.

Safety & Operational Standards

Working safely with 1-propyl-3-methylimidazolium tetrafluoroborate calls for good chemical hygiene as a basic promise. This compound can sting eyes and skin on contact, and inhalation of dust or aerosolized droplets should not be dismissed as harmless, especially during scale-up or cleanup. In my own work with ionic liquids, we always wore nitrile gloves, eye protection, and ran our reactions inside well-ventilated fume hoods, washing hands after every step. Safety data sheets demand ready access to eyewash stations and spill kits. Environmental guidelines recommend collecting liquid waste in sealed containers, avoiding release down the drain due to possible aquatic toxicity and concerns about fluorinated byproducts entering water supplies. Labs that maintain clear protocols experience fewer accidents and benefit from reliable, publishable results.

Application Area

1-Propyl-3-methylimidazolium tetrafluoroborate carved out a reputation in electrochemistry and catalysis because of its high ionic conductivity and broad electrochemical window. Colleagues in energy storage research have used it in the design of novel batteries and supercapacitors, taking advantage of its stability and ability to dissolve lithium salts. In synthesis, its solvent performance supports transition metal catalyzed reactions, where it often outpaces classic solvents by improving yields or allowing milder conditions. Some teams turn to it for biomass processing and extraction, where its selective solvation helps tease natural products from plant material with less breakdown of valuable compounds. More recently, the pharmaceutical manufacturing sector began probing ionic liquids as “tunable solvation” platforms for green processes. The versatility of this compound owes as much to its origins in fundamental research as it does to real-world industrial problems that demand creative, workable solutions.

Research & Development

Teams around the world keep pushing boundaries with 1-propyl-3-methylimidazolium tetrafluoroborate, investigating not just new reactions but also the influence of impurities, recycling, and waste minimization. In my lab, we tracked shifts in reactivity based on minor changes in cation synthesis routes, learning quickly that strict controls changed product performance. The push toward more sustainable chemical processes has made this compound a template for bespoke ionic liquids tailored for targeted applications, from CO2 capture to pharmaceutical crystallization. Some industrial researchers are mapping out the physical limitations, assessing how temperature, pressure, or extended cycling affect electrochemical behavior. At the same time, environmental scientists are optimizing ways to capture, reuse, or degrade the ionic liquid at the end of its useful life to cut down on costs and environmental impact.

Toxicity Research

Early promises held up 1-propyl-3-methylimidazolium tetrafluoroborate as an answer to the toxicity concerns of older solvents. Over the years, animal model work and in-vitro studies have revealed a more complicated reality. While the compound shows less volatility—which helps cut down on inhalation hazards—long-term studies in aquatic systems point to moderate toxicity, especially with repeated exposure or improper disposal. Studies in rodents and cells suggest low acute oral toxicity but reveal possible cytotoxicity at higher concentrations, particularly with chronic contact or if hydrolysis byproducts like hydrogen fluoride accumulate. In practice, anyone using this ionic liquid can cut down on risks by using the smallest feasible quantities, adopting closed-system experiments, and following up-to-date disposal guidelines published in peer-reviewed journals and regulatory documents.

Future Prospects

Growing demand for efficient, safe, and environmentally mindful chemical processes keeps pushing 1-propyl-3-methylimidazolium tetrafluoroborate into new territory. Next-generation batteries, supercapacitors, and even carbon capture systems could benefit from ongoing improvements in stability and selectivity. In the coming years, more companies will likely roll out customized ionic liquids, adjusting cation and anion structures to fit each application. Any future growth requires honest accounting of safety concerns—especially environmental fate and toxicity—alongside rigorous, transparent research. Ongoing collaboration between academic labs, industry, and government helps shape reasonable regulations while encouraging breakthroughs that place safety and sustainability above mere convenience or short-term productivity.

What Sets This Ionic Liquid Apart

1-Propyl-3-methylimidazolium tetrafluoroborate stands out for its ability to dissolve a broad range of materials, from salts to natural polymers. I’ve come across it in research projects where stubborn compounds needed a helping hand. Instead of relying on old-fashioned volatile solvents, this ionic liquid offers a safer, less flammable choice. That’s a big deal in crowded labs and tight industrial spaces.

Green Chemistry and Synthesis

Chemists now look for ways to cut down on toxic waste. In this push toward green chemistry, ionic liquids have found a solid place at the bench. 1-Propyl-3-methylimidazolium tetrafluoroborate works well as a solvent in organic reactions like alkylation and coupling. Traditional solvents often bring risks of environmental harm and workplace exposure. Swapping them out for this ionic liquid drops emissions and cuts the risk of fire. Its stability makes it fit for reactions at higher temperatures, which opens more doors in synthesis.

Batteries and Energy Storage

Researchers in battery technology have experimented with this compound as an electrolyte. Regular batteries, especially those in electric cars or stationary storage, use liquid electrolytes that can catch fire or break down. 1-Propyl-3-methylimidazolium tetrafluoroborate stands up better to heat and stays stable under stress. Tests show improved cycle life in lithium-ion cells. The push for longer-lasting, safer batteries has pushed interest in this class of material, and there’s data out there that backs up claims of lower flammability and good conductivity.

Separation Techniques and Extraction

Industries that rely on extracting metals, purifying waste streams, or separating chemicals face pressure to find new solutions. This ionic liquid has attracted attention as a replacement for volatile organic solvents in extractions or liquid-liquid separation. Copper, palladium, and other metals can be extracted from ores or electronics with this approach. My own experience with solvent extraction always showed the downsides of fumes and clean-up, but ionic liquids like this one make the process much safer and easier to recycle.

Biotechnology and Drug Delivery

Handling biological molecules can be tricky. Enzymes and proteins often break down or lose function in traditional solvents. 1-Propyl-3-methylimidazolium tetrafluoroborate has shown promise in keeping enzymes active longer, which helps with producing drugs or breaking down waste. A study I read last year suggested some formulations can boost how well drugs dissolve, potentially helping patients absorb medicines faster.

Potential Solutions and Future Directions

Cost remains a barrier for wider use. Production scale drives the price, so more companies entering the market could change things fast. Researchers look for ways to recover and recycle the ionic liquid after use to bring down costs and limit waste. Regulations in North America and Europe have always focused on exposure and disposal of chemicals, so it helps that this ionic liquid rates low for volatility and toxicity based on published safety sheets.

If we want greener labs and safer factories, compounds like 1-propyl-3-methylimidazolium tetrafluoroborate point to the future. With improved recycling, better supply chains, and more research, its use could become far more common across fields ranging from chemistry and energy to medicine.

Understanding the Backbone

Ionic liquids, including 1-propyl-3-methylimidazolium tetrafluoroborate, shape much of the conversation in new-age solvent chemistry. This isn’t just hype driven by niche research. Here’s a liquid that can handle heat, dryness, and isn’t spooked by air. That alone makes a strong case for its popularity in advanced lab routines and industrial setups—especially when handling stuff that shies away from water.

Learning from Real Use

I’ve seen chemists rely on this ionic liquid because it stands up to heat better than most. Typical laboratory runs toast it up to 200°C with barely a whisper of decomposition. That’s more than you get from a lot of organic solvents, and it opens doors for processes where old-school choices would simply fizzle out. That said, once you start getting past 250°C, you’re pressing your luck. The bond holding the tetrafluoroborate anion together eventually starts to buckle, and you risk splitting off boron trifluoride and toxic vapors. Nobody wants that in their hood or their lungs.

It’s not just about high highs, either. 1-propyl-3-methylimidazolium tetrafluoroborate shrugs off moisture and oxygen in most normal conditions, so you won’t lose sleep over bottles gone bad in a cool, dry cabinet. That’s a nice change from solvents where even a lazy cap leaves a mess. The chemical stays clear and dependable—less fuss for researchers and less wastage for companies counting their pennies.

Where the Cracks Show

Every chemical has its weak spots. Here, it’s strong acids and bases. Mix it with concentrated hydrochloric acid or sodium hydroxide, and the scene changes fast—degradation happens, and you’re left with boron-based byproducts that stick around and can clog up your system. In my own runs, I’ve watched as imidazolium rings turn into new, unwanted products when the pH swings too wildly. You don’t bounce back from that kind of mistake—you clean up and start over. So, run your reactions mild or neutral, and you’ll sidestep most nasty surprises.

Environmental Pressure and Solutions

Some talk about the so-called “stability,” but forget that tetrafluoroborate anions have a life cycle too. They don’t break down quickly in the environment. There’s risk of groundwater contamination, especially near chemical plants or universities that dispose of spent ionic liquids. Years ago, I joined a campus initiative to catalog solvent waste, and we traced a direct line from improperly-treated ionic liquid dumps to soil issues. Modern green chemistry aims for alternatives—safer anions, biodegradable cations. It’s common sense, and it’s starting to make a dent, but there’s a long way to go before ionic liquid waste becomes truly manageable.

Charting the Future with Facts

1-propyl-3-methylimidazolium tetrafluoroborate isn’t indestructible, but it gives solid performance under heat, air, and reasonable moisture. The compound lags behind where acids or bases slam it, and it creates environmental questions that researchers can’t ignore. I respect its reliability on the bench, provided the operator knows the playbook and stays out of the red zones. The answer—at least in my experience—is to use it with eyes wide open, testing new greener alternatives, and never underestimating the afterlife of chemicals once they leave the flask.

Looking Closer at Everyday Safety in Chemical Labs

Ask anyone who’s ever spent time in a research lab, and you’ll hear stories about odd-sounding chemicals that hide behind long names. 1-Propyl-3-methylimidazolium tetrafluoroborate sounds like something out of a science fiction novel, but it sits in bottles on real laboratory shelves, playing a role in green solvents and ionic liquid research. Getting familiar with its risks means more than just skimming a safety data sheet, because real people mix, pour, and clean up these chemicals every day.

Hazards Beyond the Label

Reading through chemical hazard databases and publications, this ionic liquid rarely receives the reputation of being acutely toxic like cyanide or nerve gases. That said, downplaying risk isn’t the same as being safe. The structure—an imidazolium cation paired with a tetrafluoroborate anion—throws up some flags, especially for anyone who has seen fluorine chemistry go sideways.

Contact with skin often causes irritation. Data from lab accidents and toxicity tests reflect both the expected sting and longer-term skin dryness. Splash some of it into eyes and that irritation jumps—think redness, watering, pain. Ingestion is worse: studies in lab rats show gastrointestinal pain, ulcers, even liver and kidney stress after exposure. Nobody enjoys reading those animal studies, but they do put real risk into perspective.

I always tell younger chemists—don’t assume that a lack of acute toxicity label means a free pass. Ionic liquids can enter the bloodstream through cuts or damaged skin. Wear gloves. Research at the University of North Texas and similar labs shows exposure over time can cause genotoxic effects, affecting the DNA itself in mice and small model organisms. While there’s still a lot to learn about what happens in people over decades, that uneasy uncertainty alone is a reason to act with caution.

Tetrafluoroborate and its Tricky Side

Now, about the tetrafluoroborate part. Under regular conditions, it stays put, but introduce strong acid or high heat and you risk producing hydrogen fluoride—a toxic and corrosive gas, well known as a skin and bone destroyer. I’ve seen stories of careless disposal leading to dangerous releases, and no safety shower can fix a pocket of HF gas in a poorly ventilated room. This makes waste handling—not just use—a core issue.

Managing the Risk in Labs and Industry

Crowded university labs must take chemical safety seriously, because those accidental splashes and inhalations happen more often than most admit. Fume hoods are essential. Proper gloves—not latex, but nitrile or better—help keep the material away from hands. Labeling and sealed storage reduce spill risk, especially since transparent bottles can make accidental swapping all too easy in a rush. I’ve had colleagues double-check container labels, especially after hearing about mix-ups that left people with skin burns and hospital visits.

Waste disposal stands as one of the biggest headaches. Never dump residues down the drain. Authorities in the US and Europe classify both this ionic liquid and contaminated tools as hazardous waste, mainly due to possible hydrolysis to HF. Collection for specialized disposal carries a cost, but it’s cheaper than dealing with a costly cleanup or injury lawsuit.

Weighing the Benefits and Safety

Green chemistry trends push more labs to adopt ionic liquids, seeking alternatives to flammable organics. For all the promise, safety must match innovation. Every new solvent on the bench comes with fresh risks and new questions. Paying attention to real exposure experiences, adjusting training in labs, and never assuming “low volatility” means “harmless”—these steps prevent mistakes from turning into injuries.

Understanding the Substance

1-Propyl-3-Methylimidazolium Tetrafluoroborate serves as an ionic liquid in various laboratory and industrial settings. This compound supports tasks from electrochemistry to advanced synthesis. Such value demands thoughtful storage practices, not only for performance but also for safety and longevity.

Why Storage Matters

Anyone who’s handled ionic liquids knows they can pick up moisture from the air in a flash. Even brief exposure to humidity can spark unwanted side-reactions or degrade product quality. Storing this chemical in a tightly sealed container keeps that trouble at bay. Glass bottles with PTFE-lined caps or high-quality plastic containers work well for this job. In my own experience, glass usually stands up to chemical leaching better over time.

Temperature plays a big role here, too. Leaving bottles out on the benchtop means risking subtle decomposition, especially if the workspace faces daily temperature swings. A cool, consistently dry place extends shelf life and keeps the material close to its data-sheet specifications. My preference lands on a dedicated desiccator cabinet. That way, the product dodges not just moisture but temperature spikes common in storage rooms.

Moisture and Contamination Risks

Some might think “dry storage” sounds overblown—but water can sneak in fast, even through a slightly loose cap. Ionic liquids absorb water quickly, and in some cases, this can change viscosity and even chemical reactivity. In shared labs I’ve seen bottles pick up water in less than a week, leading to wildly inconsistent experiment results. Using molecular sieves or desiccant packs inside storage cabinets cuts down on that risk. It’s a simple step with a big payoff in reliability and safety.

Labeling and Safety Practices

Walking into a lab with unmarked or poorly marked bottles changes the tone of any safety audit. Every bottle should wear a clear label, noting the contents, date received, and hazard information. Hanging onto the original packaging material saves time and keeps information handy for audits. If you move a portion of your chemical to another container—never trust your memory, write it down right away. In some workplaces, this step has averted mix-ups that could have endangered coworkers.

Working around chemicals comes with risk. While 1-Propyl-3-Methylimidazolium Tetrafluoroborate lacks the volatility of some other solvents, it’s smart to wear gloves and goggles during all handling, especially in cramped spaces where spills can move quickly. I’ve seen minor skin irritation from spills due to poor handling—nothing life-threatening, but annoying and avoidable.

Ventilation and Emergency Planning

Even with non-volatile chemicals, it makes sense to store them away from open flames, strong bases, acids, and incompatible materials. Storing the compound in a space with decent ventilation keeps air fresh and mitigates any risk from accidental spills or decomposition. It’s wise to keep a spill kit close by, with absorbent material ready. Quick response beats wishful thinking every time. Planning for problems, even unlikely ones, keeps teams safe and stress down.

Ongoing Monitoring

No storage setup runs on autopilot. Checks every few months ensure caps stay tight, desiccant still works, and labels remain readable. Spotting issues early—like cracked lids or moisture inside containers—has saved my labs from losing valuable stock to contamination and waste.

Building Better Habits

Proper storage helps scientists and technicians get reliable results while staying safe. Using sealed containers, controlling humidity, keeping things clearly labeled, and maintaining a tidy environment create conditions for real progress. These aren’t just checkboxes—they’re habits that protect both people and research budgets. Anyone working with sensitive chemicals like 1-Propyl-3-Methylimidazolium Tetrafluoroborate sees the payoff every day, in safer labs and more dependable results.

Understanding Purity: Why It Matters

High purity remains the gold standard for chemical compounds, whether for research, food production, pharmaceuticals, or industrial uses. Laboratories trust materials measured at 99% or higher, while manufacturers often select grades that hover just below that level for practical reasons. Purity impacts both performance and safety. Impurities can derail chemical reactions, damage sensitive equipment, and endanger health. Years ago, a misplaced fraction in a reagent led to weeks of confusion in a friend’s lab—quality mattered more than we realized.

Raw materials for the food industry often require food-grade certifications and clarity around trace contaminants. Pharmacies look for even more detail, scanning for heavy metals and residual solvents. Electronics sometimes raise the bar further, focusing on parts per million or even parts per billion impurities, given the sensitivity of semiconductor processes. These standards keep products safe, effective, and consistent.

What to Expect from Purity Grades

In most catalogs and safety sheets, purity breaks down into several categories. Technical grade usually covers materials above 90%. Lab or reagent grade refers to products reaching at least 98%. Pharmaceutical or food grade leans into 99% and above, each backed by documents such as certificates of analysis and safety data.

End-users still need to read the fine print. Even within a grade, subtle differences can impact results. A biologist told me once how trace iron in a “high purity” compound wiped out weeks of cell cultures. Quality assurance teams dig into these details, often in painful depth, because the smallest slip carries serious risk. Reliable suppliers always provide clear analytical data, which never takes the place of double-checking, especially when stakes run high.

Packaging Sizes: Matching Supply to Need

Over years of ordering, it becomes clear that packaging sizes aren’t just arbitrary units—each size matches a common need. For labs, smaller packs—10 grams, 50 grams, 100 grams—save space and minimize waste. Some catalogues list tiny vials of just a few milligrams for rare or expensive reagents. These sizes also make record-keeping easier, helping researchers track use and avoid contamination.

Industries, on the other hand, lean toward larger volumes. Kilos, 25-kilogram bags, and drums scale up for manufacturing runs or bulk processing. Shipping and storage rules shape the options, and regulations for hazardous goods often require special labeling and containers. One industrial client ordered chemicals only in sealable HDPE drums after a spillage incident led to a costly environmental cleanup—a decision born out of hard experience.

Some suppliers accommodate flexible batch sizes, especially for custom blends or rare compounds. Speaking from my time working with project procurement, direct discussion with vendors made life easier, especially for new product trials. It helps to communicate use case, storage constraints, and frequency of orders.

Practical Solutions for Reliable Supply

Buyers who care about quality and safety stick to reputable sources. Trusted distributors, transparent certificates, and open channels for technical support—these are the signals of reliability. Many companies double up on their supplier list, reducing the risk of disruption, especially for critical ingredients. In food processing and pharma, traceability remains key. Keeping detailed purchase records and certificates, plus periodic retesting, keeps surprises at bay.

Common wisdom from years in the business: communicate. Clear questions about grades, packaging, contaminant levels, and shelf life pay off every time. No shortcut replaces a good conversation with a knowledgeable rep. Whether buying for research or production, attention to purity and packaging goes a long way in ensuring safety, efficiency, and success in every batch.