1-Propyl-3-Methylimidazolium Trifluoromethanesulfonate: Unpacking a Modern Chemical Workhorse

Historical Development

The evolution of ionic liquids like 1-Propyl-3-Methylimidazolium Trifluoromethanesulfonate (commonly known as [PMIM][OTf]) traces back to the relentless search for alternatives to volatile organic solvents. Although imidazolium-based salts entered labs in the last quarter of the 20th century, the mainstream embrace of these materials only picked up in the 1990s. I still remember the cautious optimism among chemists who hoped these “green solvents” could shake up synthesis and extraction. Academic labs started investigating [PMIM][OTf], drawn by its remarkable thermal and chemical stability, and news about its utility spread through specialist conferences and niche journals. Demand within both academic and industrial circles ramped up as folks realized how the properties of this class differed from those old flammable organics.

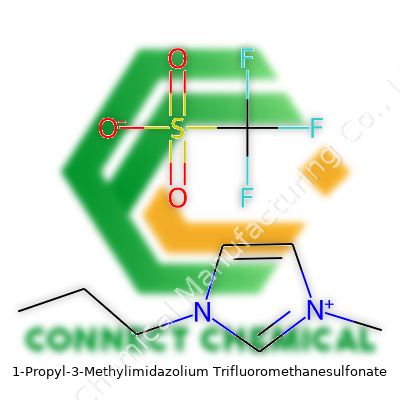

Product Overview

1-Propyl-3-Methylimidazolium Trifluoromethanesulfonate surfaces as a colorless to pale-yellow, viscous liquid at room temperature. The molecular scaffold includes a propyl and methyl group linked to imidazolium—an aromatic, nitrogen-rich ring—teamed up with a trifluoromethanesulfonate anion. Labs and manufacturers classify this salt as an ionic liquid because of its low melting point and liquid range over a wide temperature window. Scientists and engineers favor it for work in homogeneous catalysis, extraction, and electrochemistry, thanks to its unique ionic nature and minimal vapor pressure. It rarely evaporates, even at higher temperatures, sidestepping many hazards that plague classic volatile solvents.

Physical & Chemical Properties

On the bench, [PMIM][OTf] shows off a density of roughly 1.3 g/cm³ at 25°C, signaling its solid feel in the hand. Its viscosity hovers between 50–100 mPa·s, so it pours much more sluggishly than water, which can take some getting used to during transfers. Solubility patterns tell another story: it handles water, alcohols, and a range of polar organic solvents without breaking a sweat. Its high ionic conductivity partners well with electrochemical uses. Unlike older solvents, it remains chemically stable up to about 350°C, only decomposing or reacting in the face of truly aggressive reagents. The triflate anion, bristling with fluorine atoms, adds to its durability and slight hydrophobic edge, fending off many reactive species.

Technical Specifications & Labeling

Suppliers offer [PMIM][OTf] with purities above 99%, an assertion backed up by NMR, Karl Fischer titration for water content, and ion chromatography for residual halides. Labels must specify batch number, purity, water content (less than 0.2% frequently), and trace metal content, since impurities can hamper sensitive applications. Transparent labeling matters—every researcher knows how much time gets wasted troubleshooting poor results when solvents don’t meet stated specs. Properly sealed containers keep out atmospheric moisture and CO₂, since the triflate can otherwise proxy for mild acid in unwanted hydrolysis or side reactions.

Preparation Method

Lab synthesis of [PMIM][OTf] often follows a two-step route. It starts with alkylation of 1-methylimidazole using 1-bromopropane, yielding 1-propyl-3-methylimidazolium bromide. This intermediate then undergoes a metathesis reaction with silver trifluoromethanesulfonate in water or acetonitrile, swapping the bromide for the triflate anion. Filtration removes precipitated silver bromide, and the resulting solution dries under reduced pressure. Some prefer ion-exchange columns, but I’ve found the silver-triflate method cleaner for making crystal-clear batches with low residual halides. Careful attention during drying and storage keeps degradation at bay, especially when planning for sensitive transformations.

Chemical Reactions & Modifications

[PMIM][OTf] resists many pathways that break down regular solvents. Strong bases or nucleophiles can attack the imidazolium ring under forcing conditions, though most synthetic applications run far short of that threshold. Minor tweaks to the propyl or methyl group yield a suite of similar salts—tuning hydrophobicity, viscosity, and thermal stability. Labs have even grafted functional side chains onto the imidazolium, creating tailored ionic liquids for unique extraction or catalytic jobs. The triflate anion can be swapped for other non-coordinating groups, but I’ve noticed that OTf lends better electrochemical stability than sulfonates like tosylate under high current or potential applications.

Synonyms & Product Names

Manufacturers and literature may call this molecule 1-propyl-3-methylimidazolium trifluoromethanesulfonate, [PMIM][OTf], or 1-propyl-3-methylimidazolium triflate. Trade names pop up too: PMIM OTf or simply PMIM triflate. Staying alert for synonyms matters, as mixing up chemical names with similar structures can trip up even seasoned chemists, especially when switching suppliers. CAS numbers (not listed here as requested) serve as the final authority for procurement to avoid mix-ups.

Safety & Operational Standards

People sometimes hear the phrase “green solvent” and think it means safe. While [PMIM][OTf] doesn’t evaporate into flammable vapors like ether or chloroform, skin contact can still cause irritation. I always suit up with gloves and safety glasses before cracking open a bottle. Direct skin, eye, or respiratory contact deserves real caution—ionic liquids in general carry uncertain toxicity profiles since they aren’t as thoroughly tested as legacy materials. Exhaustive risk assessment remains essential for new processes employing ionic liquids. Good ventilation and avoidance of high-temperature decomposition products help sidestep health hazards. For spills, absorb with inert material and dispose in accordance with hazardous chemical protocols—never wash down the drain.

Application Area

Researchers reach for [PMIM][OTf] when ordinary solvents let them down. I’ve found it invaluable in electrochemistry, where stable and wide potential windows enable studies that classic solvents just can’t match. Catalysis teams lean on its miscibility with transition-metal complexes to drive cleaner and faster conversion. Battery development counts on its high ionic conductivity and low volatility to support safe, high-performance electrolytes—especially for next-generation lithium and magnesium batteries. Extraction chemists exploit its selectivity for metal ions, while separation scientists harness its ability to dissolve cellulose or biopolymers that water and regular organics won’t touch. Green chemistry groups praise its recyclability and low vapor pressure as a means to avoid emission headaches, though proper disposal and regeneration require dedicated infrastructure.

Research & Development

Much of the innovation in ionic liquids boils down to new compositions, but application specialists keep tweaking [PMIM][OTf] for more sustainable syntheses. Recent papers highlight its use in carbon capture, taking advantage of the imidazolium ring’s interaction with CO₂. Battery groups build new formulations for solid-state and flexible electronics, hoping to overcome the breakdown and aging issues witnessed in early devices. Lab-scale pilot processes test recovery and purification cycles, since many industries now face pressure to tighten the loop on chemical use and emissions. Collaborative research ties chemistry and process engineering, since scaling ionic liquid systems can clash with legacy plant equipment. The challenge becomes finding ways to bring small-batch chemical miracles into the real world, where economics and supply chain reliability still dictate winners.

Toxicity Research

Researchers examining toxicity point out that, despite low volatility, long-term exposure or improper handling can carry health risks. Cytotoxic studies show that high concentrations disrupt cell membranes and metabolic pathways, particularly in aquatic organisms. Chronic aquatic toxicity led regulators to monitor waste streams more closely, as traces persist in water columns. Human ingestion or dermal exposure remains ill advised, so engineering controls and personal protection stand as daily practice. My own lab never assumes new ionic liquids are benign—each gets a full review before use, pulling toxicity data from fresh studies wherever possible. Regulatory science still plays catch-up, and until databases fill out, prudent handling and waste management lead the way.

Future Prospects

Ionic liquids like [PMIM][OTf] look set for widespread adoption in green energy technologies, sustainable manufacturing, and specialty chemical production. Battery makers crave electrolytes that stay stable after hundreds of cycles, and this triflate salt draws attention for its performance in this niche. Advances in synthesis and purification could bring costs down, making it practical even outside high-value processes. New regulations on emissions add pressure for rethinking solvent systems across pharmaceuticals and fine chemicals, so long-term growth depends on safety data, lifecycle assessments, and supply chain transparency. Though challenges persist, [PMIM][OTf] stands out as one of those rare cases where clever chemistry and real-world needs line up, promising tools that help science and industry alike push forward.

Pushing Chemistry Forward in the Lab

People working in research live and breathe new ways to get chemicals to work together. 1-Propyl-3-Methylimidazolium Trifluoromethanesulfonate, better known as a type of ionic liquid, can change the game. Unlike traditional solvents, it doesn’t evaporate easily, and it offers a special set of chemical properties—high stability, and the power to dissolve all kinds of compounds, both organic and inorganic. In my own university days, trying to force two stubborn reagents together, an ionic liquid like this one often helped where older tools fell short. Suddenly, stubborn reactions would run faster, with cleaner results, and safer handling because there were fewer toxic vapors to worry about.

Chemists craving to cut down on waste and risk look toward ionic liquids for exactly that reason. Research published in Green Chemistry highlights just how much solvent use in the pharmaceutical sector can shrink if these liquids step in. Less waste in the lab means less risk for workers and for the environment outside.

Energy Storage: Batteries Growing Up

Ask anyone following battery science, and they’ll say today’s energy needs demand better materials for the guts of batteries. 1-Propyl-3-Methylimidazolium Trifluoromethanesulfonate doesn’t just sit in a flask—this liquid shines as an electrolyte. The very structure of this chemical lets ions flow smoothly, which boosts charge and discharge performance in lithium batteries. My friend in battery development always points out that batteries with these ionic liquids handle higher temperatures and store more energy without risking those frightening battery fires.

Industry research has found that these electrolytes cut down on the flammability risks that haunt lithium-ion technology. The boom in electric vehicles and grid storage won’t wait for better safety, so materials like this step up. Electrification of transportation and backup power for homes could lean on these advances, making the energy transition both safer and more efficient.

Catalysis and Cleaner Production

Old-school chemical factories run processes that eat up harsh acids or bases, often leading to pollution issues. Bring in an ionic liquid, and the waste stream changes. 1-Propyl-3-Methylimidazolium Trifluoromethanesulfonate can boost catalytic cycles, letting the same expensive catalyst work for more runs before replacement. I remember a site visit at a specialty manufacturing plant, where switching to ionic liquid catalysts let them recover precious metals almost completely—less loss, less need to buy more, and far less clean-up work at the end.

Some studies from the American Chemical Society note that using ionic liquids for catalysis cuts dangerous byproducts and uses less nasty reagents. This win matters for chemical workers and neighbors living downwind.

Looking Ahead: Room to Grow and Improve

This chemical has impressed experts in lab work, battery research, and sustainable manufacturing. Still, wide adoption faces hurdles. Higher costs and the fine art of recycling these liquids after use need work. Scientists are digging into how to reuse and purify ionic liquids after an industrial run, to limit both expense and potential environmental impact.

Policymakers and industry insiders have an opening here. By funding research on recycling processes, or creating incentives for greener solvents, society can tip the scales. Step by step, chemicals like 1-Propyl-3-Methylimidazolium Trifluoromethanesulfonate could show up in more real-world products and services, helping to shrink chemical waste and support safer technology.

Understanding the Chemical

1-Propyl-3-methylimidazolium trifluoromethanesulfonate belongs to a family of chemicals often known as ionic liquids. Unlike traditional solvents, these compounds tend to remain liquid over a broad range of temperatures. Scientists appreciate their stability, low vapor pressure, and their unique ability to dissolve tough materials. People working in labs or at chemical plants sometimes treat these ionic liquids like miracle substances, but every great tool has a flip side.

What’s Known About Safety

I’ve handled a range of chemicals in industrial chemistry labs, and anytime you see the words “trifluoro” or “sulfonate,” a person pays attention. These components don’t guarantee trouble, but they do signal the need for a closer look. Most ionic liquids lack a long track record for long-term health risks, but some reports reveal skin and eye irritation can happen with direct contact. Animal studies on related compounds sometimes suggest toxicity if swallowed in significant amounts. Breathing mist or fine particles could cause respiratory problems.

Digging through material safety data sheets, I see calls for goggles, gloves, and good ventilation. That’s not unusual for lab chemicals, but it does remind people not to treat these substances with casual care. The low vapor pressure often gets pitched as a safety perk—less stuff evaporates into the air. The reality: a spill sticks around a lot longer than with alcohol or acetone. A careless cleanup lets more people get exposed through skin contact.

Environmental Hazards

Ionic liquids get advertised as “green” solvents, but that’s sometimes marketing talk. Some break down slowly, not at all, or into unknown byproducts. Trifluoromethanesulfonate doesn’t come from nature; water treatment plants weren’t built to filter it out. If the liquid reaches water supplies, fish or aquatic plants can’t easily process it. Data from studies using zebrafish embryos or other freshwater animals suggest that some ionic liquids can stress these organisms, change growth patterns, or even cause early death. If a facility dumps large volumes, problems could pile up over months or years before anyone notices.

Choosing Sensible Protections

Whenever a new or rare compound hits the bench, simple habits go a long way to prevent accidents. In my experience, the best labs treat every unfamiliar liquid as if it could harm the skin, lungs, or eyes. Full-length gloves, wraparound goggles, and fume hoods protect workers. Nobody wins by skipping a step just because the chemical smells harmless or doesn’t turn up on a “dangerous substances” list.

For storage and disposal, keeping the ionic liquid contained limits leaks and accidental mixing. Many facilities store these in chemical-resistant, labeled bottles and separate waste for special collection. Trying to wash the substance down the drain could send persistent chemicals straight into rivers or lakes. Third-party disposal is pricier, but cleaning up after an environmental release costs much more.

Looking Ahead

The chemistry community always calls for more public data before declaring a new chemical “safe.” If people need to work with 1-propyl-3-methylimidazolium trifluoromethanesulfonate, they’ll want clear facts about risks, protections, and long-term effects on both people and water systems. Start with the basic protections. Push for routine reviews of health studies and waste management practices. Regulators, researchers, and workers should keep asking questions until the answers add up.

Understanding the Substance

1-Propyl-3-Methylimidazolium Trifluoromethanesulfonate lands on the bench of many labs looking for efficient solvents or electrolytes. This ionic liquid brings high thermal stability and non-flammable nature, and it starts showing up in work that deals with organic synthesis and batteries. Still, safety doesn’t just come from a chemical's reputation for stability.

Personal Experience with Safety

Handling chemicals in research always brought a mix of curiosity and caution to my day. I’ve seen well-organized spaces and I’ve seen chaos—but spills or unexpected reactions happened quickest when someone skipped safety steps. Even if you trust a compound’s track record, slips in habits lead to more risk than the liquid itself. Wearing proper gloves—nitrile stands up best—keeps skin from the risk of irritation. Good lab coats, eye protection, and access to washing stations are must-haves.

Labeling and Storage Practices

Clear labeling stops confusion and keeps surprises to a minimum. A bottle left out with a faded label, especially with a liquid like this one, invites mistakes. Keep the name, concentration, date opened, and hazard warnings easy to spot.

Shelves near direct sunlight, heaters, and open flames can push ionic liquids like this out of safe temperature zones. I’ve found that room temp works for storage, but never stack these bottles somewhere humid. Moisture creeping into a bottle changes qualities you count on, sometimes breaking down purity.

Safe Handling Habits

Pouring and measuring this trifluoromethanesulfonate takes a steady hand. Pour in a fume hood even though the risk of fumes runs lower than with many solvents. Any spill carries cleanup headaches since this liquid feels slippery and traces can cause slips or unwanted cross-contamination.

Good air flow helps. Modern fume hoods catch what you don’t see. Even a small amount can go on gloved fingertips and onto surfaces, so keeping work areas uncluttered and wiping them down after use makes a noticeable difference. I’ve seen experiments ruined by leftovers from the last user—preventable with the right habits.

Waste and Disposal

Build up a habit of collecting waste in marked, sealed containers. Tossing this type of waste down the sink leads to trouble with pipes and environmental compliance. Handing over to professional waste services matches best with environmental rules and keeps drains clean. Local waste procedures may shift, so keep up with the guidelines that fit your location.

Thinking Ahead: A Culture of Responsibility

Mistakes in lab culture rarely come from lack of data—they come from cutting corners. Training everyone who steps in the lab to handle ionic liquids responsibly keeps the space safe for all. Refresh safety protocols once a year, if not more. Always ask about new handling tips; collective experience often goes further than any instruction manual.

Labs thrive on trust and openness around risks. If someone misses a spill or handles waste casually, correct in the moment. With proper labeling, good storage, a commitment to actual safety gear, and regular waste checks, labs can avoid turning a useful chemical into a headache. Trust grows when people know what’s in every bottle and treat each one with respect.

Understanding What We Get

People often ask, “What is the purity and specification of the product supplied?” The answer means much more than a number on a certificate. Purity reflects how closely the product matches what a buyer expects. Specification shows us the way each batch lives up to promises made at the time of sale. Every day, choices in sourcing and quality checks either support or undermine these outcomes.

Why Purity Matters in the Real World

I’ve seen how even minor slips in quality can turn a routine job upside down. In pharmaceuticals, small impurities spark recalls and health scares. Food companies face consumer backlash if there’s an unexpected contaminant. In batteries and electronics, trace metals that don’t belong can wreck months of work. Purity isn’t about perfection; it’s about protecting safety, value, and trust.

The Specs Tell Us What to Expect

Suppliers publish specifications for a reason. Specs go beyond just how much pure material sits in a drum—they cover everything from trace metal levels to pH, moisture content, and even particle size. These criteria often come from tough international standards, like those set by ISO or the United States Pharmacopeia. Meeting these standards often leads to contracts, while missing them sinks deals quickly.

Facts That Keep Us Grounded

Product specifications aren't just box-ticking exercises. They reflect years of research and careful negotiation between buyer and seller. For example, pharmaceutical raw materials rarely stray from 98-102% purity according to suppliers like Merck and Sigma-Aldrich. Industrial chemicals may run lower or higher based on use—battery-grade lithium always arrives above 99.5% purity, while bulk salt for roads carries lower purity and looser specs.

Tough suppliers run analyses using gas or liquid chromatography, atomic absorption, and other trusted tests. The data makes it easier to catch shortfalls early. Companies with a track record of consistent, high-quality analysis earn more business over time. Buyers start to rely on trust—built not only by numbers on a datasheet but by prompt resolutions when things don’t go as planned.

Why Problems Happen

Contamination creeps in from poor storage, careless handling, or even the raw materials used to make the product itself. Sometimes cost-cutting limits how much quality control happens. Other times, people rush production to meet deadlines and skip checks entirely. I’ve watched quality teams struggle when suppliers offer batches “within spec” that still cause real-world problems. It’s usually not just a lab issue—it’s a communication breakdown between customers and suppliers who don’t share the same priorities.

What Can Everyone Do Better?

There’s a strong case for demanding transparency at each stage. Real trust develops when suppliers explain how they test, what limits they accept, and how buyers can double-check those results independently. In my own experience, the best outcomes start with clear agreements. When both sides invest in regular quality audits and share results, headaches fade. Problems catch early and team morale climbs.

Many successful companies act on the idea that prevention costs less than a recall or lost client. Upfront investment in lab training, regular equipment calibration, and open feedback loops keeps everyone accountable. At the end of the day, purity and specification affect more than just a number—they shape how safe, reliable, and successful we can be in business and in life.

A Close-Up on Ionic Liquids

Ionic liquids caught my attention in the lab back in grad school. The promise of safer, more stable electrochemical solvents always had a certain pull—especially after enough afternoons spent sniffing noxious ether or watching volatile chemicals eat through gloves. 1-Propyl-3-methylimidazolium trifluoromethanesulfonate (let’s call it PMIM OTf for simplicity) steps up as a strong candidate for work that calls for both reliability and innovation.

Why Electrochemists Notice PMIM OTf

This compound boils down to a few practical qualities. PMIM OTf’s ionic structure won’t evaporate or catch fire under typical working conditions. That changes a lot in a world where water, acetonitrile, and other standard solvents bring their own headaches—flammability, volatility, or poor stability for wide voltage windows.

In research communities, the PMIM cation already has a rep for high chemical and thermal stability. Its OTf anion remains resistant to reduction and oxidation across a broad voltage range. That means this ionic liquid supports many electrochemical reactions without breaking down or gumming up your experiment. Add low viscosity and good electrochemical windows, you get smooth ion transport and efficient current flow—something every battery or supercapacitor researcher appreciates.

Safety and Sustainability in the Lab

Health and safety enhance the case for PMIM OTf. Traditional organic solvents rank among the biggest hazards in electrochemistry. Ionic liquids like PMIM OTf don’t evaporate easily, so researchers can breathe a little easier—literally. Less vapor means fewer risks and a cleaner workspace. While not entirely “green,” ionic liquids show lower environmental impact over time compared to legacy materials that quickly escape into the air or water streams.

Practical Results in Energy Research

Lab tests show PMIM OTf supports stable ion conduction and robust voltage windows—stretching further than most organic solvents. This opens possibilities for new battery systems. Lithium-ion battery research, for instance, has benefited from PMIM OTf’s broad stability, lowering the risk of dendrite growth or electrolyte degradation throughout charging cycles. Supercapacitor and fuel cell teams often report improved cycle lifetimes and safety benchmarks when using this ionic liquid.

Of course, every material has limits. PMIM OTf’s water affinity can pose problems in humid environments, where moisture seeps in and steals performance. Careful storage and handling fix some of this, though complete moisture exclusion takes real effort. Another challenge: ionic liquids carry a price premium, with higher costs than most everyday electrolytes, making them trickier for consumer products outside specialized fields.

Opportunities and Solutions

Scaling production and finding ways to recycle or regenerate ionic liquids cut costs in the long term. Academic labs and industry projects both look for second-generation designs—mixing PMIM OTf with other ionic liquids or small additives—that keep all the good attributes but push performance even higher. Cleanroom practices, vacuum ovens, or continuous flow drying help limit water pick-up and stretch shelf life.

In my own work, I’ve seen researchers swap volatile organic solvents for PMIM OTf and get sharper voltammograms, with less noise and fewer safety alerts. Collaboration between electrochemists, green chemists, and industrial engineers—sometimes even pulling in startups focused on recycling—shows promise. As the field pushes for energy storage breakthroughs, safer labs, and greener processes, the role of advanced ionic liquids like PMIM OTf only grows more urgent.