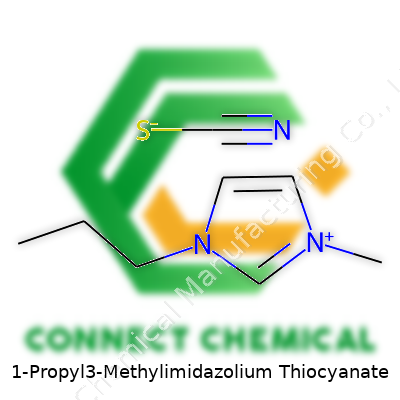

1-Propyl-3-Methylimidazolium Thiocyanate: Past, Present, and Future

Historical Development

Chemists first started thinking more seriously about ionic liquids in the late 20th century, mainly because traditional solvents brought their own problems—volatility, toxicity, and persistent pollution. 1-Propyl-3-methylimidazolium thiocyanate, often recognized in labs by the shorthand [PMIM][SCN], belongs to the family of imidazolium-based ionic liquids that caught serious attention during green chemistry’s rise. The initial synthesis of related imidazolium salts dates back to the 1980s, but researchers in the 1990s unlocked the door by swapping out counter-ions like chloride for functionalized anions such as thiocyanate. That move opened broader potential for customization and innovation, giving scientists tools that not only dissolve an impressive range of compounds but also avoid many of the harsh downsides of classic solvents. As environmental regulations and sustainability standards tightened, popular trade journals began to show a growing body of research where [PMIM][SCN] and its cousins played a starring role in chemical processes that simply could not be performed as efficiently any other way.

Product Overview

1-Propyl-3-methylimidazolium thiocyanate surfaces in catalogs targeting advanced materials research, electrochemistry, and select industrial extraction processes. It’s a room-temperature ionic liquid—a liquid salt that stays fluid under standard lab conditions, breaking old ideas about what makes a compound “liquid.” The product presents as a colorless to pale yellow liquid, with a faint characteristic odor and a dense, viscous flow. Producers usually supply it in amber glass bottles or sealed polypropylene containers, shielding it from light and moisture, both of which can degrade ionic stability over longer periods. Labs purchase it with varying purity levels, topped with certificates of analysis and storage directions that recommend keeping it between 15°C and 30°C, tightly capped and safely away from heat sources.

Physical & Chemical Properties

This ionic liquid stands out for its low melting point (often around -20°C), enabling use at ambient temperatures. It typically boasts a density near 1.1–1.2 g/cm³ and impressively low vapor pressure, which sharply restricts flammability and unwanted evaporation. The high thermal stability, usually up to about 250°C before decomposition, allows reactions that require robust solvents. Its viscosity greatly depends on temperature, thicker at lower temperatures and thinning as it warms, somewhat like syrup but with far more chemical intrigue. Strong polarity, coupled with ample hydrogen bonding from its constituent ions, lets it dissolve a wide menu of inorganic and organic compounds—including some that normally resist traditional solvent systems. Solubility in water varies based on the charge distribution of the thiocyanate anion and the length of the propyl group, lending flexibility in applications ranging from hydrophilic to hydrophobic environments.

Technical Specifications & Labeling

Reputable suppliers arm each bottle with detailed labeling: chemical name (1-propyl-3-methylimidazolium thiocyanate), Empirical Formula (C7H13N3S), CAS Number (varies; best to reference up-to-date catalogs), batch number, and purity (generally >98%, with lower levels reserved for bulk industrial use). Safety and hazard pictograms follow globally harmonized system (GHS) standards, highlighting precautionary measures. Technical sheets explain compatible materials, incompatible chemicals (notably strong oxidizers and materials sensitive to nucleophilic attack), and recommendations for waste disposal. Despite rich customizability at the industrial level, labs prioritize traceability and purity, mandating tight tracking from synthesis right down to final delivery.

Preparation Method

Most laboratories reach this ionic liquid through quaternization followed by metathesis. The route starts by alkylating 1-methylimidazole with 1-bromopropane, producing 1-propyl-3-methylimidazolium bromide. This intermediate salt, once purified and dried, brings in the critical thiocyanate counterion via a salt metathesis reaction: mixing the bromide with sodium thiocyanate in water or appropriate alcohol. Filtration and solvent evaporation give the desired product. Final purification often uses activated charcoal and vacuum drying, chasing away traces of halide, unreacted reagents, and water that threaten product stability or interfere with sensitive applications like battery electrolytes or analytical extractions.

Chemical Reactions & Modifications

1-Propyl-3-methylimidazolium thiocyanate excels as a reaction medium for nucleophilic substitution, oxidation–reduction, and a handful of condensation reactions that struggle under classic conditions. Its immiscibility with certain hydrocarbons, yet strong solvation of polar species, means it often partitions products and byproducts, simplifying post-reaction separation. Modifications come from tuning either the alkyl substituents on the imidazolium ring or swapping out the anion altogether. Adding functional groups to the alkyl chains can adjust viscosity, hydrophobicity, or even coordination properties with transition metals. Anion exchange opens doors to custom solvents for specific catalytic cycles, especially in organometallic and peptide chemistry.

Synonyms & Product Names

Published literature and commercial catalogs list the compound by several names: 1-propyl-3-methylimidazolium thiocyanate, PMIM-SCN, [PMIM][SCN], and less formally as imidazolium thiocyanate ionic liquid. Alternate abbreviations pop up, but the chemical community tends to standardize on [C3mim][SCN] or 1-propyl-3-methylimidazolium thiocyanate for clarity in publications and regulatory filings. Recognizing synonyms avoids confusion in multinational research collaborations where naming conventions vary by journal and lab.

Safety & Operational Standards

Handling ionic liquids with imidazolium cores requires gloves, goggles, and local ventilation. Though 1-propyl-3-methylimidazolium thiocyanate remains stable on the bench, spills can cause skin and eye irritation. Accidental ingestion or inhalation brings risk of toxicity, so labs treat even small-scale working stocks as chemical hazards. Waste management practices treat the liquid as a specialty organic, separating it from halogenated and non-halogenated solvents to satisfy regional environmental controls. Regular risk assessments, especially in pilot plants or upscaled processes, ensure accidental releases do not contaminate soils or wastewater. Recent policies in the European Union and North America increasingly focus on ionic liquid lifecycle management, challenging manufacturers to track residues and persistent environmental traces over longer timescales.

Application Area

Researchers lean into [PMIM][SCN] for extraction of metal ions, particularly precious metals and rare earth elements, from aqueous or mixed matrices. Its high coordination ability with transition metals supports separation of closely related ion pairs that traditionally pose stoppage points in hydrometallurgical efforts. Electrochemists use it to build up stable, non-flammable electrolytes for high-voltage batteries and supercapacitors. In biochemistry, this liquid fosters protein dissolution and maintains enzyme activity under non-standard conditions, crucial to refolding studies and proteomics. The broad solvating power stretches into organic synthesis, particularly where classic solvents either destroy yield or introduce destructive impurities. Industrial clients trial it in continuous-flow reactors and materials processing, since the negligible vapor pressure cuts emissions—a persuasive argument where regulatory fines loom over volatile organic compound usage.

Research & Development

Active R&D focuses on fine-tuning ionic liquid properties for niche processes. Ongoing projects explore alternate anion and cation pairs to push boundaries on thermal stability, electrical conductivity, and biocompatibility. Computational researchers use quantum chemical modeling to forecast reactivity, seeking deeper understanding of how the liquid matrix mediates catalytic events at the molecular level. Analytical chemists experiment with [PMIM][SCN] as a dual-purpose medium—solvent and reactant—in microextraction or mass spectrometry workflows that demand ultra-low blanks and non-interfering sample matrices. Partnerships between academia, national labs, and private industry drive initiatives to improve green chemistry credentials, scrutinizing by-product profiles and long-lived environmental waste.

Toxicity Research

Knowledge about long-term safety evolves as more data lands from laboratory and environmental fate studies. Acute toxicity seems low by comparison to many organics, but repeated exposure and break-down products bring reason for caution. Cell-based assays and ecotoxicology screens keep uncovering subtle bioaccumulation and cytotoxicity risks that guide safe use limits. The thiocyanate ion’s established presence in biological systems brings an extra wrinkle, since overexposure disrupts thyroid metabolism in both lab animals and humans. Professional organizations, including the American Chemical Society, push for ongoing chronic exposure studies before scaling up industrial adoption. Safe disposal receives heavy emphasis in lab practice, with chemical fume hoods and neutralization steps designed to prevent spread into public water streams or landfill sites.

Future Prospects

Experts expect ionic liquids like [PMIM][SCN] to unlock new chemistries as the climate for clean technology heats up. Battery innovators look to these compounds for electrochemical stability unreachable with classic salts. Bio-refinery processes promise extraction of pharmaceuticals and nutraceuticals with smaller ecological footprints, fueled by solvents that don’t evaporate or ignite. Widespread adoption hinges on better toxicity understanding, simpler recycling technologies, and optimized production at scale. The next decade will likely revolve around the ability of these innovative liquids to solve problems long considered unsolvable in separation, catalysis, and advanced material synthesis. The work sits at the intersection of chemistry, environmental science, and engineering practice—exactly where new answers to sustainability pressures need to come from.

Understanding the Role of This Ionic Liquid

1-Propyl-3-methylimidazolium thiocyanate belongs to a class of chemicals called ionic liquids. These aren’t just regular salts; they stay in a liquid form at room temperature and pack some unusual features. Researchers and companies use them because they hardly evaporate, they dissolve a wide range of materials, and they don’t catch fire easily. These traits set them apart from traditional organic solvents, which often carry safety or environmental risks.

Solvent in Chemical Reactions

In my work with chemical labs, swapping out regular solvents for ionic liquids like this one has meant less handling of smelly, dangerous chemicals. For chemists, this makes daily routines safer. 1-Propyl-3-methylimidazolium thiocyanate dissolves both organic and inorganic compounds. This allows labs to work with stubborn or sensitive chemical mixtures. People in research choose it when they need solvents that won’t vaporize or catch fire, especially during experiments that require steady conditions over long hours.

Material Processing and Synthesis

Industries depend on ionic liquids to tweak materials and boost efficiency. In battery production, for example, ionic liquids replace flammable solvents in electrolytes. This improves the safety record of lithium-ion batteries and opens doors to safer energy storage. The thiocyanate component brings extra value, helping in the extraction of certain metals from ores. This becomes a key step for electronics recycling and refining precious metals in a more environmentally responsible way.

Green Chemistry and Sustainability

Over the years, I noticed a real push in labs toward greener approaches. Ionic liquids like 1-propyl-3-methylimidazolium thiocyanate become attractive because they cut down on toxic chemical waste. Once they replace volatile organic solvents, air pollution drops. Their persistence in chemical setups allows companies to use less, since one batch can withstand several cycles. In wastewater treatments, these ionic liquids help remove dyes and heavy metals that old techniques leave behind. This matters in places where water quality impacts crops and community health.

Challenges and Looking Ahead

Not every solution is free from problems. Ionic liquids sometimes cost more than older chemicals and can take longer to break down in the environment. Some studies raise questions about long-term effects if they end up in rivers or soil. The goal now is tighter recycling systems inside factories and more transparency with environmental impact data. Manufacturers who communicate honestly about product life cycles and safety records give customers more confidence.

Emerging research also focuses on customizing ionic liquids for even safer, more efficient applications. Experts in academia and industry have started to explore how these compounds handle new renewable energy tech, advanced plastics, and electronics. As supply chains grow stronger and research delivers clearer evidence of their safety, ionic liquids like 1-propyl-3-methylimidazolium thiocyanate could become a fixture in both the lab and the factory. Supporting this shift means encouraging responsible use, continued research, and up-front disclosure about health and environmental impacts.

Understanding What’s at Stake

1-Propyl-3-Methylimidazolium Thiocyanate falls into a category of chemicals that can surprise even experienced lab workers. This ionic liquid has found use in research labs, especially for its solvating properties and electrochemical work. It comes off as easy to handle, but this is only true up to a point. If you assume bare hands and casual attitudes work here, think again.

Personal Protective Gear Matters

Personal safety gear isn’t just for show, and folks who get lazy with their gloves or skip their face shields are rolling the dice. Direct contact with this chemical can cause irritation. Nitrile gloves stand up well against most ionic liquids. I’ve seen colleagues try standard latex; they found out later their gloves didn’t hold up—not a pleasant discovery with skin reactions lingering for days. Lab coats should button up snug, and splash-proof goggles go a long way in stopping any near-miss from turning into an emergency-room visit.

Keep Workspaces in Check

Spills don’t just clean themselves up. I remember a time someone left a small droplet on the back counter—by the time it was noticed, it etched a faint ring into the bench and caused a panicked scramble for the proper neutralizer. Absorb spills with vermiculite or a similar inert material, and never, ever use bare hands. Contaminated material belongs in a secure, labeled waste container that matches your facility’s chemical disposal rules. Your nose isn’t a gas detector, but decent chemical fume hoods are. Work only with good airflow, and don’t pop open containers near vents or hot plates.

Safe Storage Means Fewer Problems

This compound needs storage away from heat and direct sunlight. Even in a dark, labeled bottle, you need to keep it capped tightly. Water and other common solvents can trigger unexpected reactions, so don’t tuck this bottle next to acids or bleach. Every year, some lab somewhere gets a harsh lesson after storing incompatible chemicals too close.

First-Hand Wisdom: Avoiding Shortcuts

The urge to rush spills over, especially near the end of a long shift. Skipping the full check on a storage cabinet or racing through a cleanup can push a simple task into an incident that lingers in memory for all the wrong reasons. If you work in a busy environment, it helps to build habits around double-checking labels and organizing the workspace before starting anything. Mixing bottles, misreading a cap—these small mistakes stack up.

Solid Habits Outweigh Fancy Tools

Expertise doesn’t always come from the fanciest equipment. I’ve worked in labs that did more with caution, teamwork, and plain old checklists than ones stocked with every new safety gadget. A trained eye catches leaks. Clear communication keeps people out of harm’s way when moving chemicals. Routine safety meetings, even if they get groans, make a difference in staying sharp and sharing near-miss stories.

Moving Forward Responsibly

Regulatory agencies like OSHA and the CDC set rules for chemical handling for a reason, and experience has taught me that shortcuts backfire. Regular training keeps everyone up to speed on handling new compounds and refining protocols when things change. Facilities that reward speaking up about hazards see fewer injuries than those where silence rules. Responsible handling doesn’t just protect one person; it shields everyone who shares a workspace and the environment outside those walls.

Recognizing Ionic Liquids in Everyday Applications

People working with chemicals often run into words that sound more complicated than what’s going on in the beaker. 1-Propyl-3-methylimidazolium thiocyanate falls into a class known as ionic liquids. These are salts that actually remain liquid even at room temperature. That property has meant big things in fields like solvents for chemical reactions, electrochemistry, and even sustainable energy. You might not see this bottle by your sink, but in research labs it’s pretty common.

Breaking Down the Chemical Structure

To understand what 1-Propyl-3-methylimidazolium thiocyanate is, looking at both sides of the formula helps.

- Cation: The first half—1-propyl-3-methylimidazolium—comes from imidazole, a five-membered ring with two nitrogen atoms. Chemists swap two hydrogens with methyl (CH3) and propyl (C3H7) groups so you end up with a big, bulky positive ion: C7H13N2+.

- Anion: The second half—thiocyanate—is simple: it’s an SCN- group, one sulfur, one carbon, one nitrogen.

Why This Matters in Modern Chemistry

Ionic liquids like this one have a real boost over traditional solvents or salts—they rarely evaporate under normal lab conditions, so accidents from fumes drop. They also often show a huge range of things they dissolve, from chunky polymers to gnarly metal complexes, and respond well to electricity. Many researchers across pharmaceutical, material science, and industrial sectors chase after substances that cut down on waste and risk, and many have stories of trying to separate tricky chemical mixtures with less hazardous materials. Options like 1-propyl-3-methylimidazolium thiocyanate deliver on all these fronts.

Environmental and Safety Considerations

Just because something is called “green” doesn’t always mean it solves every problem. Many ionic liquids don’t easily break down in water or soil. I’ve seen teams wrestle with how to recycle or dispose of them, since simply pouring leftovers down the drain can contaminate water supplies. Handling and disposal need strong protocols, and as more scientists work with these compounds, regulators look for data on toxicity and environmental persistence. More research aiming to design safer, biodegradable versions keeps popping up.

How to Move Forward with Ionic Liquids

If you walk into a lab storage closet, you find way more solvents and salts than this single example, but what sets 1-propyl-3-methylimidazolium thiocyanate apart is the creative space it provides. Tinkering with different side chains on the imidazolium ring has led to new formulas with different solubility, melting points, and reactivity. People now test out entirely new applications—in batteries, sensors, smart materials—hoping to tap something safer and more efficient.

For the next breakthrough, it helps to pair chemical know-how with common sense about environmental impact and hands-on safety plans. While the formula—C7H13N2SCN—may not roll off the tongue, understanding why it matters and how to use it responsibly opens the door to real-world solutions.

A Closer Look at Chemical Storage

Back in my early days in a research lab, I learned quickly how a lapse in chemical storage could ruin an experiment—or put someone at risk. Take something like 1-Propyl-3-Methylimidazolium Thiocyanate. It sits among the vast family of ionic liquids, often praised for unique physical and chemical features, but even routine chemicals demand respect. Mishandling something unfamiliar, even without a toxic reputation, brings its own set of problems.

The Need for Dry, Cool, and Airtight Conditions

I once watched a whole batch of expensive reagent degrade just because someone thought sealing a cap loosely was “good enough.” Plenty of people have similar stories. This particular compound doesn’t tolerate moisture or light well. Moisture ends up breaking down the crystalline structure, spoiling its usefulness and potentially making it more corrosive. Heat ramps up reactivity and volatility, a bad combo for any lab or warehouse setting.

Experience shows storing it in an airtight container makes a world of difference. Sealing the chemical keeps out humidity and air, protecting its structure and purity. Stash that container in a cool spot, away from sunlight—think a cabinet or a chemical fridge—not next to windows or radiators. Avoid the temptation to use unmarked or makeshift bottles; labeled, chemical-resistant vessels cut out confusion and accidents. Anyone working near these chemicals deserves clear information and safe storage habits.

Workplace Culture and Training Keep People Safe

Technical guidelines help, but habits form the real backbone of chemical safety. I’ve seen labs where even trained staff ignored posted warnings, storing ionic liquids next to incompatible acids or oxidizers. One mix-up is all it takes. Facilities that emphasize ongoing training and make materials available shape safer employees. Mixing up acids, bases, and organic chemicals creates fire or toxic gas hazards—even a label mix-up becomes a big deal fast.

Safety data sheets sit at arm’s reach in responsible facilities. Workers should know the compound's properties on day one—physical hazards rarely hide their effects. The best-run labs I’ve been in run regular training and emergency drills. This lets everyone react quickly if a leak or spill happens, even early-career staff. Teaching proper storage keeps surprises to a minimum.

Handling Waste and Minimizing Risks

No one wants to spend half a day cleaning up spilled chemicals. It’s better to control the risk from the start. I’ve seen practical solutions keep things orderly: spill trays beneath containers, vented storage spaces, and scheduled checks of inventory. A missing cap leaves more than just fumes—it wastes money and exposes staff. Unused chemicals should never languish in forgotten back corners. Prompt disposal through a certified chemical waste company avoids future hazards, both for people and the wider environment.

Better Lab Habits Build Trust

Chemicals like 1-Propyl-3-Methylimidazolium Thiocyanate may sound technical, but the best practices for keeping them stable are basic: dry storage, cool temperatures, and sealed containers. Lab and industrial teams who pay close attention reduce accidents, save money, and build strong trust. Sharing stories and simple guidelines keeps old mistakes from repeating. Respecting the storage of every chemical, regardless of how mundane, protects everyone’s work and well-being.

What Makes This Compound Special?

Anytime someone asks about 1-Propyl-3-Methylimidazolium Thiocyanate (often called [PMIM][SCN]), the talk circles around ionic liquids. This molecule forms when a specially designed imidazolium cation pairs up with a thiocyanate anion. Scientists have had their eyes on these compounds because they serve as unique alternatives to traditional solvents. Trying to get away from the nasty volatility of old-school organics, researchers choose ionic liquids hoping for less hazardous, more versatile chemical options. Water solubility ends up right in the spotlight for anyone working with them.

Does 1-Propyl-3-Methylimidazolium Thiocyanate Dissolve?

Based on published laboratory reports, 1-Propyl-3-Methylimidazolium Thiocyanate dissolves well in water. Ionic liquids in the imidazolium family (especially those with small alkyl chains and hydrophilic anions) tend to have good water solubility. Here, the cation carries a propyl group, not too bulky, and the thiocyanate – which loves polar solvents – helps this salt blend smoothly into water. Direct solubility measurements show complete mixing at room temperature. Try it yourself in a lab, and you’ll get a clear solution after a quick swirl. This property matters for researchers looking for easy clean-up, mixing, or post-processing without fussing over hazardous waste streams.

Why Does Solubility Matter for Chemistry and Industry?

Ionic liquids often get a reputation for flexibility in research. Water solubility opens a lot of doors. For example, if you’re developing sensors or extraction techniques, solubility in water means direct compatibility with biological systems and easy integration with environmentally friendly processes. In my early career uses involving ionic liquids, every time a salt blended seamlessly with water, purification steps simplified and yields improved. Chasing after new ways to do chemistry without troublesome organic solvents, many labs want ionic liquids with this trait.

Digging into the numbers, a paper by Robinson et al. (J. Chem. Eng. Data, 2022) measured the solubility as over 50 g/L at room temperature. You’d be hard-pressed to find a more convenient choice if your goal is aqueous compatibility. This solubility means that any project involving catalysis, synthesis, or extraction in water can use this compound without designing elaborate workaround procedures.

Potential Drawbacks and Ways Forward

Great as it sounds, water-loving ionic liquids create clever problems. High solubility sometimes leads to difficulties removing the salt after a reaction, especially if you need to recover both product and solvent. Traditional organic solvents evaporate or separate out, but a dissolved ionic liquid can linger in every drop. In a few of my own water-based separation attempts, this increased the need for more advanced purification—dialysis, ultrafiltration, or creative crystallization—to get pure product. Not everyone wants to add extra steps to their workflow.

This challenge paves the way for further solutions. Chemists have started developing “switchable” ionic liquids, which can change solubility with a little heating, pH tweak, or gas bubbling (like CO₂). Imagine a thiocyanate ionic liquid that dissolves during the reaction but could be recovered right after by a simple temperature change. Water solubility gives huge benefits at the bench, but it’s wise for anyone scaling up a process to plan for how to recycle or separate these materials if they hope for a green and cost-effective operation.

Real-World Use and Sustainable Practice

Interest in substitutes for volatile organic compounds pushes labs to seek greener chemicals. Water-miscible ionic liquids like 1-Propyl-3-Methylimidazolium Thiocyanate hold potential to bridge the gap, making procedures cleaner and sometimes safer. With the added bonus of being able to blend right into water, they knock over old barriers in process design. Anyone stepping into ionic liquid chemistry will appreciate this trait, though careful thinking about downstream recovery options is just as important for sustainable science.