1-Sulfobutyl-3-Butylimidazolium Hydrosulfate: A Ground-Level View of a Modern Ionic Liquid

Historical Development

Ionic liquids started turning heads in the late 20th century, promising a new kind of chemical platform thanks to their low volatility and unique solvating capabilities. 1-Sulfobutyl-3-butylimidazolium hydrosulfate came into sharper focus as labs sought compounds with both green chemistry credentials and broad applicability. As awareness of environmental impacts grew, research funding for ionic liquid synthesis and potential applications followed. The material’s roots stretch back to the search for new solvents in catalysis and extractions, steadily shifting toward substances with less human and environmental risk than traditional organic solvents. My time in research showed how collaboration and government grants, driven by environmental policy trends, compelled scientists to pivot toward ionic liquids like this one—hungry for viscosity, recyclability, and heat tolerance without high emissions.

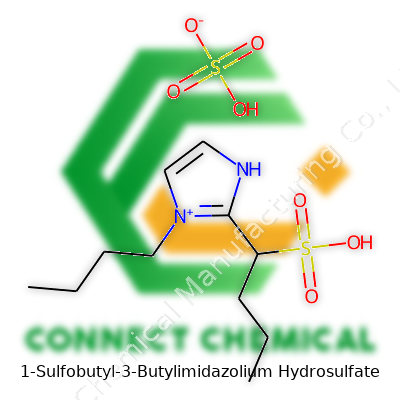

Product Overview

This compound stands out for its dual imidazolium-sulfonate structure. Featuring both hydrophilic and hydrophobic chains, it blends well in polar and non-polar systems. Its hydrosulfate counterion offers an acidic element, bringing catalytic value alongside solvent action. The distinct pairing of butylimidazole with sulfonate doesn’t just drive interest among chemists looking to develop catalysts or enzyme systems, but also catches the eye of engineers who want reliable performance when other solvents fail.

Physical & Chemical Properties

This ionic liquid offers a clear, often colorless or slightly yellowish appearance, a density near 1.2 g/cm³, and a melting point typically below room temperature—it remains liquid across a wide thermal window, sidestepping crystallization concerns that plague many other salts. Its viscosity can run high, a detail felt in the lab during pipetting, yet this viscosity also brings advantages for reactions demanding temperature stability. Water solubility is solid, but distinct layers can form at high concentrations. Its ionic conductivity ranks high, making it valuable for use in electrochemical cells and other electronics-adjacent projects. Its unique acidity opens catalytic doors and grants special solubility profiles in both simple and complex reaction media.

Technical Specifications & Labeling

Commercially produced bottles often come labeled with purity above 98%, trace metals kept below 10 ppm, and water content below 2%. Material safety data sheets always call out hygroscopic properties, which means it pulls moisture from the air. I’ve learned through use that container selection and dry storage prevent unexpected hydrolysis or reactivity. Handling large volumes pushes buyers to look for certifications meeting both European REACH and American TSCA regulations.

Preparation Method

Synthesis begins with the alkylation of imidazole, introducing a butyl group, followed by attachment of a sulfobutyl side chain—either by alkylsulfonation or Michael addition. The final ion exchange with sulfuric acid yields the hydrosulfate salt. The process leans on relatively straightforward organic chemistry tools without exotic reagents, which helps keep production costs and workplace hazards in check. My direct experience with small-batch synthesis underscored the need for slow addition of the sulfate to avoid exothermic runaway reactions; scale-up often uses jacketed glassware and careful temperature control for safety and yield.

Chemical Reactions & Modifications

1-Sulfobutyl-3-butylimidazolium hydrosulfate steps up as both solvent and reagent. It can promote esterification, alkylation, and transesterification, reducing the need for traditional mineral acids. Modifications to its side chain can tailor polarity or steric effects, which in turn opens up new reaction pathways or enhances selectivity. Its cation supports further functionalization, so chemists routinely try swapping hydrosulfate for other counterions to tune acidity or reactivity. I watched colleagues in academia add halide scavengers or transition metals, transforming the base compound into a series of task-specific ionic liquids, each with tweaks for solubility or catalytic enhancement.

Synonyms & Product Names

Literature and product catalogs use names like SBIMHSO4, 1-sulfobutyl-3-butylimidazolium hydrogen sulfate, or simply [SBuIM][HSO4]. Researchers searching patent databases or safety paperwork must keep these variants in mind. Chemical supply companies sometimes abbreviate or rebrand for ease of marketing; this doesn’t affect how the material performs but makes thorough cross-checking crucial during procurement or regulatory review.

Safety & Operational Standards

The compound remains stable under normal temperatures but reacts with strong bases and oxidizers. Gloves, goggles, and a well-ventilated fume hood form the backbone of safe handling. My lab’s approach also called for spill containment—viscous liquids can spill and are hard to clean, so planning ahead makes a difference. Waste disposal rides on local regulations, with most jurisdictions classifying waste as non-volatile yet requiring neutralization before drain disposal. MSDS sheets also insist on eye-wash stations and proper training before use. Regulatory trends increasingly expect closed-system transfer and measures to track trace environmental release.

Application Area

Researchers and industry engineers put this material to work in green chemistry, catalysis, and electrochemistry. It shines in acid-catalyzed transformations, biomass processing, and separation science, finding a niche in pharmaceuticals and fine chemicals where solvent recycling and tolerance to reactive intermediates matter. My own R&D showed that it can improve yields in Fischer esterification, while researchers in battery development point to its role as a high-performance electrolyte additive. New projects explore its use in protein extraction and enzyme stabilization, taking aim at more sustainable industrial processing.

Research & Development

The research field remains lively. One big draw is the push toward tunable solvents for difficult reactions, where this molecule’s blend of acidity and stability walks a fine line. Industry consortia and public labs probe combinations with nanomaterials, renewable feedstocks, and hybrid catalysts. Grant programs lean in the direction of materials with lower toxicity and full lifecycle assessments. From a personal standpoint, the abundance of journal articles and conference posters on ionic liquids over the last decade points to continuous competition and innovation. Those in academia regularly translate R&D insights into pilot-scale production to gauge economic viability.

Toxicity Research

Current toxicity reports suggest low volatility helps limit inhalation risk, but dermal and oral exposures need careful management. Long-term environmental fate studies remain limited, yet most data indicate persistence, with some breakdown possible through photolysis or advanced oxidation. Risks around aquatic toxicity keep environmental scientists cautious during scale-up. In practice, lab users rely on PPE and containment, while larger producers run occasional life-cycle analyses to spot and fix any red flags. Many studies now build comparative datasets with other ionic liquids to map risks and tradeoffs.

Future Prospects

Looking ahead, demand for non-volatile, reliable, and recyclable industrial fluids positions compounds like 1-sulfobutyl-3-butylimidazolium hydrosulfate for growth. Ongoing legislative shifts toward green chemistry create tailwinds for adoption. Researchers worldwide hunt for greener, less toxic, and more cost-effective ionic liquids—driving competition and continuous improvement in both production methods and safety processes. Based on my experience, big breakthroughs likely won’t come from a single star performer, but rather from a family of related compounds, each adapted for specific use-cases. With sustainability metrics under more scrutiny, both regulators and customers will demand more data and better stewardship—pressing the industry to innovate not just in function, but across the entire lifecycle of the molecule.

Real-World Uses and Impacts

1-Sulfobutyl-3-butylimidazolium hydrosulfate falls into the family of ionic liquids. These are not your ordinary salts; they stay liquid below 100°C and can dissolve all sorts of materials that water or oil alone would struggle with. In my years working with green chemistry, I’ve seen how substances like this one can open doors in both labs and industry.

This particular ionic liquid gets a lot of attention in research circles because it stands up to heat, doesn’t catch fire easily, and avoids the volatility of traditional organic solvents. If you’ve ever tried to run a reaction that needed to stay away from flammable fumes, you quickly appreciate the value those features bring. In the pharmaceutical world, extracting or separating complicated molecules often calls for a gentle touch—or at least a medium that won’t mess with sensitive compounds—so ionic liquids like 1-sulfobutyl-3-butylimidazolium hydrosulfate make sense.

Chemical synthesis labs use this compound for tasks like catalytic reactions and dissolving tough polymers. Certain cellulose extractions rely on it as a safer, less harsh solvent. I remember a project trying to process waste biomass into something useful; traditional approaches gave us headaches from the fumes, but switching to an ionic liquid changed the game. The compound let us pull out valuable chemicals without the hazard tapes and constant air monitoring.

Green Chemistry and Environmental Impact

Many folks talk about sustainability but get stuck when classic industrial solvents enter the equation. Most solvents end up as hazardous waste or evaporate into the air, harming both workers and the environment. Ionic liquids don’t evaporate off like gasoline or ether. If you’ve ever been in a facility dealing with volatile solvents, the smell lingers, and you wonder about long-term health. Swapping out those aging chemicals for something like 1-sulfobutyl-3-butylimidazolium hydrosulfate leads to much safer labs. Plus, some data shows ionic liquids can be recycled in closed-loop processes, cutting down on both waste and raw material costs.

Challenges and Ways Forward

This is not a miracle solution for every problem. People who use this compound still worry about cost and environmental toxicity. Ionic liquids tend to be expensive compared to things like ethanol or acetone. Also, chemists debate their ultimate eco-friendliness, since some types do break down into less healthy byproducts. A smart move is to invest in proper after-use treatment and design processes that reuse or recycle these liquids as much as possible. Green engineering doesn’t mean closing your eyes to downstream effects—full transparency about possible hazards and life-cycle assessments go a long way.

We see innovation driving prices down as manufacturers scale up. Universities and startup labs keep publishing fresh ways to recover and reuse ionic liquids, including the one at hand. Combining careful waste management, worker training, and smarter process design, the future of chemicals like 1-sulfobutyl-3-butylimidazolium hydrosulfate looks brighter. Careful application makes it a powerful tool, not just another chemical on the shelf.

Why Storage Makes a Difference

Handling chemicals at the bench, a person learns quickly which ones demand respect. 1-Sulfobutyl-3-butylimidazolium hydrosulfate stands out as one you don’t just toss onto a shelf with the rest. Moisture, air, contamination—those can quickly turn a usable ionic liquid into wasted resources. I’ve seen researchers lose entire batches because their bottles sat open too long or picked up dust from a cracked cap. Safe storage stretches far beyond keeping a workspace tidy; it’s about making sure an expensive purchase or labor-intensive synth doesn’t vanish in a week.

Keeping Things Cool and Dry

This ionic liquid prefers temperatures far from the heat of a sunlit window or a radiator. Aim for cool, stable climates—some recommend room temperature as long as it stays consistent and away from spikes. Direct sunlight invites decomposition, the same as with many organic compounds. Ultraviolet rays can wreck chemical structure faster than most folks expect.

Humidity can sneak into bottles in poorly sealed environments. Since this compound absorbs water from the air, high humidity leads to clumpy solids or diluted solutions. I always stash sensitive chemicals with silica gel packets or inside a desiccator chamber for this very reason. That extra protection keeps the substance in good shape, ready for reliable results.

Choosing the Right Container

The material of the storage container matters, too. Glass bottles with tightly fitting seals work best—plastic can let in more air or chemicals over time, especially with softer polymers. A screw cap lined with PTFE (polytetrafluoroethylene) or a similar tough material keeps leaks out and prevents reactions with the lid. Labs that use snap-top bottles or reuse old packaging run higher risks, as even a slight gap lets in moisture, raising the odds of contamination.

Clear glass makes it easy to check on the contents. Look for signs like cloudiness, layers forming, or any strange colors. Any unexpected change often points to a storage issue, not just a batch gone bad. That keeps the finger-pointing down and the problem solving up.

Labels, Inventory, and Shelf Placement

A sharp marker and a clear label matter more than fancy inventory software. Date each bottle. Write out the storage recommendation as a reminder for yourself and anyone else in the lab. Returning chemicals to the wrong shelf—a damp corner or next to reagents that vent corrosive gases—has ruined more than one experiment where I worked. Mixing storage with incompatible materials like strong bases or acids can lead to unexpected interactions.

Keep the hydrosulfate away from places where it might pick up detritus or corrosion (think: old shelves, rusty metal tools). Place it on a clean, solid shelf, at eye height if possible. That lowers spill risks, especially for people grabbing similar bottles quickly.

Why This Matters in Real Labs

Ionic liquids like this one cost real money. Buying in bulk saves some, but only if every bottle stays fresh. Proper storage prevents loss, accidents, and skewed data. Researchers rely on consistent quality and availability—the alternative is painful: repeating failed syntheses, recalculating experiments, and dealing with frustrated teams. Good habits around storage set the groundwork for everything from safe handling to dependable science.

Better Practices, Better Results

Careful attention to temperature, humidity, container, and shelf space guarantees any investment in this chemical pays off. These simple rules have saved me from wasted time and expense, not just for hydrosulfate, but for every specialty compound lining those shelves. Reliable storage means more confidence in every experiment, and that’s worth far more than any saved penny.

Understanding the Chemical

1-Sulfobutyl-3-butylimidazolium hydrosulfate serves a niche role in labs. You see it pop up every now and then in green chemistry papers or when someone talks about ionic liquids. Ionic liquids look much more harmless than harsh acids or bases—clear, oily, syrupy. But friendly appearance doesn't tell the story about risk.

Safety Facts and Hands-On Experience

Working in a research lab, I've seen students drop their guard around chemicals that lack the skull-and-crossbones symbol. Some start pouring with minimal protection, thinking the absence of bad smells or fumes means less danger. Ionic liquids, including 1-sulfobutyl-3-butylimidazolium hydrosulfate, challenge that thinking. Even compounds that don’t burn your nose can sneak up on you.

This compound carries a hydrosulfate group, and that brings the risk of acidic behavior. Handling it without gloves dries out the skin and leaves behind mild irritation. There’s also the problem of absorption—a lot of ionic liquids slide through standard nitrile gloves quietly over time. People forget that being non-volatile doesn't equate to being non-toxic. Literature from safety data sheets and peer-reviewed papers points to potential hazards like eye injury, skin reddening, and, if mishandled, respiratory stress in case of aerosol or heated vapor exposure.

What Makes Compounds Like This Tricky

Lab routines reveal that you rarely get splashed with organic solvents if you follow the protocols, but cleaning up after ionic liquid spills isn’t as simple. This substance sticks to surfaces and glassware, making decontamination a hassle. Once it gets on a bench, people end up spreading it just by touching pipettes or paper towels. Unlike water or ethanol, it leaves an invisible residue that’s hard to spot but keeps delivering exposure.

Scientific sources raise concern about persistent low-level contact. I’ve watched respected chemists develop contact dermatitis from compounds like these. They tolerated dry hands and rash, but over time, chronic irritation left lasting problems. It’s insidious because the risk isn’t dramatic. Most hazards come from forgetting that “benign” looking stuff can still cause harm with careless use. Data from occupational health journals agree: compounds with imidazolium structures often produce unexpected sensitivities when handled repeatedly without proper care.

Finding Better Solutions for Lab Safety

Old habits die hard in older labs, but even the best scientists slip into shortcuts. For ionic liquids, routine means double-gloving when scale or exposure increases, and switching gloves frequently. Chemical-resistant gloves like butyl or neoprene work better than standard nitrile for prolonged tasks. Proper lab coats and splash-proof goggles should always be worn. Using fume hoods for weighing or transferring the compound cuts down on any accidental inhalation risk, especially if heated or handled in bulk.

Spill kits tailored for sticky organic liquids need to be nearby, not buried on a shelf. Training newcomers to treat unfamiliar chemicals with respect always pays off. Manufacturers and suppliers need to communicate hazards clearly—sometimes new researchers only see the “green” label and ignore long-term safety notes. Sharing experiences, both good and bad, helps labs make smarter choices about what to use and how to use it. Lab culture guided by caution and openness makes sure compounds like 1-sulfobutyl-3-butylimidazolium hydrosulfate don’t become the root of preventable problems.

Understanding the Building Blocks

1-Sulfobutyl-3-butylimidazolium hydrosulfate has a name that twists the tongue, but its makeup boils down to a blend of organic creativity and sulfur’s touch. Picture an imidazolium ring. Chemists often pick this ring for its stability and role in ionic liquids. Tied to one nitrogen on the ring, you’ll find a straightforward butyl group – four carbon atoms lined up in a chain. The other nitrogen isn’t left plain – it connects to a sulfobutyl chain. Here, four more carbons trail out, crowned by a sulfonate group (–SO3−). Charge matters here, and this heavy sulfonate ends up balanced by a hydrosulfate anion (HSO4−).

What the Structure Brings to the Table

Start looking at practical use, and you see people gravitating toward ionic liquids for reasons rooted in chemistry and the environment both. This compound attracts attention in labs because the imidazolium backbone provides both chemical heft and a knack for dissolving a spectrum of substances. Add in the sulfobutyl group, and the molecule finds new jobs – from fuel cell research to green solvent work.

The charge pairing between the big organic cation and the hydrosulfate anion makes the salt melt at low temperatures. Drop it in water, and the sulfonate head reaches out, pulling in moisture, acting almost like a chemical sponge. Sulfonate groups, with their three oxygen atoms glued to sulfur, bring acid strength and water compatibility.

Looking Through a Practical Lens

Research labs keep seeking ways to lower the footprint of industrial processes. Ionic liquids like this one sidestep the fire risk that dogs flammable organic solvents. I still remember the first time I watched one of these liquids get poured – stays clear, never boils, and carries a soft heft that reveals its ionic nature.

The imidazolium core, when decorated with tailored side chains, influences all sorts of performance traits. The butyl group softens the structure, giving enough wiggle room to let ions move, while the sulfobutyl portion amplifies solubility and binds with polar compounds. Having hydrosulfate in the counter-ion slot tips this liquid toward being acidic, making it a workhorse for acid-catalyzed reactions. The ability to steer between polar and nonpolar compatibility opens doors, especially in cleaning up chemical processes or stripping unwanted elements from mixtures.

Why This Structure Matters Beyond the Lab

Every chemical decision leaves a mark – on products, on surroundings, and on all of us. Imidazolium ionic liquids like this example slide into greener chemistry, stripping out harsh solvents and lowering emissions. Governments eye these compounds to help hit climate targets. From my talks with engineers, a big concern lingers: cost and recyclability. These ionic liquids perform, but recycling and recovering each drop costs brainpower and dollars. Some folks are working to make new versions cheaper or easier to reclaim.

Regulating bodies run through every new chemical, watching for hidden dangers. The sulfur in both the cation and anion means careful waste management. Researchers still run plenty of toxicity tests, especially if any compound enters streams or soils.

Facing Chemical Realities

Making ionic liquids widely accepted will mean more than clever design. Life cycle studies, real-world pilot runs, and sharp safety analysis need to back up any green claims. On a day-to-day level, cleaner and better-tailored solvents change the way researchers approach extractions, separations, and syntheses. Every molecule, including 1-sulfobutyl-3-butylimidazolium hydrosulfate, takes a team of people to shepherd it safely from flask to factory, with stops for public health and environmental checks. Reliable chemistry doesn’t just live in journals – it shapes how we all interact with products, energy, and the waste we leave behind.

This chemical's no household cleaner

Chemical names like 1-Sulfobutyl-3-butylimidazolium hydrosulfate don’t come up much in average conversation, but folks in labs, manufacturing, or research know it. Sometimes called an ionic liquid, this material pops up in green chemistry—for catalysis, solvent use, or energy storage. Its disposal presents a bigger deal than just dumping it down the drain.

Hazards aren’t always obvious

If you’ve ever handled ionic liquids, you know their hype as “green” choices doesn’t always tell the whole story. Some act less nasty than volatile organics, yet that doesn’t mean Mother Nature welcomes them with open arms. Hydrosulfate-packed ions bring acidic properties, so they can eat through pipes or harm aquatic life. It’s easy to picture small spills going unnoticed, but chronic drainage could poison a watershed or corrode city plumbing.

Rules aren’t just red tape—there’s a good reason

Regulations might feel like a drag, but they push everyone to keep people, animals, and the planet safe. The Resource Conservation and Recovery Act (RCRA) handles hazardous waste in the U.S. Ionic liquids slip under many specific categories, so you rarely see them named outright. Still, 1-Sulfobutyl-3-butylimidazolium hydrosulfate can show up as corrosive waste (D002) if it drops the pH too low, or toxic if contaminated with heavy metals or solvents. Skip the guesswork and check your Safety Data Sheet. If it flags the stuff as hazardous, treat it like one.

In the lab: Works best when everyone pays attention

Plenty of labs have made mistakes—dumping spent solvents or solutions without checking the downstream effect. I’ve seen drains clog, pipes eat through, and stories of state investigators showing up after someone poured the “wrong” thing. Folks should hold chemical waste in sealed containers, label everything to avoid mix-ups, and store it inside sturdy cabinets. Routine pickups by licensed waste handlers beat any shortcut.

Why landfills can be a bad choice

Pitching chemical waste into the regular trash sets up problems for landfill workers, waste-hauling crews, and everyone who depends on groundwater downstream. Ionic liquids can seep with rainfall, break down only partially, and end up persistent in the environment. That’s how toxins build up in food webs, even when a single batch seems small.

Incineration and neutralization: Safer ways to go

Some specialized incinerators burn hazardous waste at high temperatures to zap toxins and break complicated chemicals into safer pieces. This destroys most organic ionic liquids, although it demands energy and trained operators. A few facilities may neutralize acidic waste first, using bases like sodium hydroxide to balance pH before final disposal. Every region differs—call a hazardous waste coordinator before you assume a waste barrel is headed for the right spot.

Get ahead with planning and substitution

An ounce of prevention always makes more sense than scrambling with disposal after chemicals pile up. Substituting less hazardous materials offers a step forward. Double-check protocols to use only what you need, recycle whenever feasible, and keep up-to-date with disposal contracts.

Responsibility goes beyond the bench

Proper disposal of 1-Sulfobutyl-3-butylimidazolium hydrosulfate calls for more than ticking boxes on a form. Think about who shares the water and air. One person’s shortcut could mean years of clean-up and long-term health headaches for everyone else. Taking the time now protects both lab crews and neighbors—for real environmental progress, small careful steps can have big impacts.