1-Tetradecyl-2,3-Dimethylimidazolium Bromide: A Ground-Level Look

Historical Development

Walk through the halls of chemical innovation, and ionic liquids, like 1-Tetradecyl-2,3-Dimethylimidazolium Bromide, show up again and again in the last few decades. Folks working in chemistry labs dug deep into imidazolium compounds during the late 20th century, mainly interested in carving out materials that wouldn’t catch fire or evaporate the way common solvents did. Hands-on inventors combined long alkyl chains, such as tetradecyl, with imidazolium rings, then topped it off with halide salts. Back then, the focus ran on tailoring unique properties: people wanted robust electrochemical stability and the sort of low vapor pressure that could stand up to tough tasks. Over the years, chemical catalogs expanded, drawing attention from industry and academia in equal measure.

Product Overview

Ask a chemical supplier or a research chemist what’s unique about 1-Tetradecyl-2,3-Dimethylimidazolium Bromide and one answer tends to rise above the noise: it’s about functionality and versatility. This compound lands in the family of ionic liquids, which means it exists as a salt that melts below 100°C. Often sold as a white or faintly yellow solid, the product hits the market tightly packaged since moisture sensitivity matters. Its structure, which joins a tetradecyl chain to a dimethyl-substituted imidazolium ring and tops off with bromide, delivers impressive surface activity, strong ionic character, and pronounced solvent power.

Physical & Chemical Properties

Looking closely, this chemical usually appears as a waxy or powdery substance. At room temperature, it doesn’t flow like water, but it transitions to a liquid at just above normal indoor temperatures, maybe 50-70°C, depending on purity and humidity. The melting and boiling points reflect its long alkyl chain and strong ionic interactions. High thermal stability means it holds up under heat; the imidazolium backbone resists breakdown in chemical reactions. Its bromide counterion supports solubility in polar solvents, ensuring it doesn’t simply clump or drop out in mixed systems. This robust solubility paired with hydrophobic and hydrophilic domains makes it valuable in tailoring the environment inside a chemical reaction flask.

Technical Specifications & Labeling

Suppliers of specialty chemicals keep tight standards in labeling and specification sheets. For this product, purity often runs above 97%. Water content needs monitoring—trace water can mess with results, so lots list water below 0.5%. Impurities, such as residual starting imidazoles or partially alkylated byproducts, stay well-below 1%. Chemical labeling codes highlight potential hazards, storage temperature (room temperature, in a sealed container, out of the light), and single-use warning tags if the product touches pharmaceutical development. Barcode tracking and date of manufacture get stamped on premium shipments—researchers want to know the product source and batch number in case an issue rises downstream. Labels call out both the IUPAC and common synonyms to prevent confusion across languages and research groups.

Preparation Method

Get a flask ready, add 2,3-dimethylimidazole, throw in a long-chain alkyl bromide (like 1-bromotetradecane), and start up a gentle heat source. Nucleophilic substitution takes over, where the nitrogen atom on the imidazole swaps with the bromide, giving the final 1-tetradecyl-2,3-dimethylimidazolium bromide. Most chemists swear by using polar aprotic solvents to drive this reaction, favoring yields and reducing side-products. By-products tend to get washed out with water or polar solvents. Drying over anhydrous agents, then a solid round of purification, brings the compound to the purity level needed for careful work in research or the lab bench.

Chemical Reactions & Modifications

Workshops and university labs turn to this ionic liquid for its ability to participate in, and sometimes accelerate, organic reactions. The structure makes it a strong candidate as a reaction medium for nucleophilic substitutions, oxidations, and reductions. Certain alkyl side chains can be swapped, growing the possibilities for custom versions—improving solubility or adjusting the melting point for special tasks. Chemists also exploit its bromide site for ion exchange, swapping out bromide for other anions like BF4- or PF6-, essentially redesigning the liquid for new chemical missions. The imidazolium ring won’t break under standard lab reactions, so researchers lean on its stability to anchor new functional groups onto the chain, expanding its reactivity and compatibility with more processes.

Synonyms & Product Names

Almost every major chemical distributor lists 1-Tetradecyl-2,3-Dimethylimidazolium Bromide under its main IUPAC name. Shop around, and other names pop up: C14DMIM-Br or 1-C14-2,3-Me2IM-Br. Folks in the field will also call it “ionic liquid surfactant” or “imidazolium bromide surfactant” depending on context. Some catalogs give shorthand names, tucking it under broader “imidazolium bromides,” but the long alkyl chain always sets it apart from shorter cousins like 1-butyl variants.

Safety & Operational Standards

Lab safety officers always insist on gloves and eye protection when working with novel ionic liquids, and handling 1-Tetradecyl-2,3-Dimethylimidazolium Bromide is no exception. Direct contact can lead to skin and eye irritation. The dust lingers—avoid breathing it in. Store the compound in a dry, cool space, sealed tight from air and moisture. Spills clean up using an inert absorbent, with plenty of ventilated air to keep from inhaling any fine dust. Waste disposal protocols demand careful containment—this isn’t the kind of stuff you pour down the drain. Safety data sheets spell out risks and first aid measures, following regulatory requirements for labeling and documentation. People who spend years in the lab know how quickly standards change, so regular hazard training keeps teams sharp on the latest protocols.

Application Area

Industries hunting for stable, high-performance solvents look at this chemical as a serious contender. Electrochemists drop it in as an electrolyte for supercapacitors and dye-sensitized solar cells; its wide electrochemical window lets them push the limits without breakdown. In extraction chemistry, this ionic liquid pulls and separates compounds more efficiently than many traditional solvents. Pharmaceutical researchers use it to form novel drug delivery systems, leveraging its ability to dissolve both hydrophobic and hydrophilic compounds. Catalysis researchers build metal and organic catalysts directly inside its matrix, taking advantage of the unique microenvironment. Its surface-active properties let formulators swap traditional quaternary ammonium surfactants for this greener alternative, especially in tough industrial degreasing jobs and oil recovery processes. In my own experience, colleagues in academic labs lean on this ionic liquid during green chemistry projects—often trying to push reactions at room temperature that used to need toxic solvents.

Research & Development

Academics and industrial chemists don’t rest easy. They’re always tweaking 1-Tetradecyl-2,3-Dimethylimidazolium Bromide for higher performance, broader reactivity, and better environmental safety. Publications in journals show how substituting anions or fine-tuning alkyl chain lengths can swing properties by a wide margin: higher ionic conductivity, improved heat tolerance, faster dissolution of stubborn compounds. Lab groups focus on understanding how mixtures of ionic liquids work together, aiming for ways to cut costs and reduce toxicity. In collaborative projects, the focus often shifts to scaling up reactions that, until recently, only worked on milligram scales. The race is on to create new applications in fields as far-flung as bioseparations, chemical engineering, and materials science. Having watched students and professors go through gallons of trial and error, it’s clear that incremental research pays off—each little improvement in performance leads to sounder industrial processes.

Toxicity Research

No one can overlook the question of toxicity. Ionic liquids once sold as “green” alternatives, until folks started discovering that some structures stuck around in the environment or hurt aquatic life. For this specific compound, toxicity studies look at acute effects on skin and eyes and at broader ecological impacts. Animal testing (fish and invertebrates) shows where toxicity lands—usually scaling by the length of the alkyl chain. Longer chains often mean higher toxicity and lower biodegradability. Regulatory agencies keep a close watch, and safety research hasn’t answered every question yet. Most in the chemical industry push for more biodegradable versions or build in “green” side chains that break down faster in the wild. From personal talks with environmental colleagues, it’s clear: new chemicals have to earn their place by proving they don’t cause more harm than the ones they replace.

Future Prospects

More research pours in each year. As industries demand less volatile, safer solvents, compounds like 1-Tetradecyl-2,3-Dimethylimidazolium Bromide attract more attention for use in batteries, extraction, and catalysis. Academic labs, especially groups focusing on sustainability, keep searching for ways to break down ionic liquids after use without special processing plants. The future likely holds more custom variants, tailored for targeted applications, and green chemistry standards will push chemists to design safer, more biodegradable ionic liquids. Whether in advanced electronics or new industrial cleaning techniques, the next wave of projects will demand solid data on safety, recyclability, and cost. I’ve noticed more undergraduates taking on research in this field—they’re not just hunting good grades; they’re looking for smart solutions to old problems. The best shot for this class of molecules lies in responsible stewardship and honest science: research that doesn’t shy away from tough questions or unknowns.

Digging Into the Facts

1-Tetradecyl-2,3-dimethylimidazolium bromide might sound arcane, but its role shows up in real-world science and industry. With experience working around chemical labs, the true value of this compound often reveals itself in how it carries a burden others can’t. Its structure lands it in the group of ionic liquids—salts that stay liquid not just at high temperatures, but sometimes even at room temperature. Unlike the strong chemical smell that queues up when opening a bottle of acetone or toluene, these chemicals tend to bring a gentler touch, making workspaces far more comfortable—and safer—for the folks who spend hours there.

Chemistry’s Handyman

Chemists reach for 1-tetradecyl-2,3-dimethylimidazolium bromide in tasks that demand something more than water or alcohols. Its surfactant behavior can bust up dirt or oil films, lending a hand in cleaning up glassware and, on a bigger scale, helping break down stains in industry. In my own laboratory days, it turned out to be an ace at helping dissolve stubborn organic compounds. The long carbon chain grabs at oils, and the ionic part can tug at polar substances—this double act makes it a lifesaver when separating messy mixtures or recycling used catalysts.

Pushing Research Forward

Green chemistry stands to gain from this kind of ionic liquid. The world chases less toxic, less volatile solvents for everything from pharmaceuticals to biotechnology. This compound replaces more toxic cleaning agents, lowering long-term risk for both workers and the environment. In chromatography and chemical synthesis, swapping in a well-designed ionic liquid often means fewer spills, less hazardous waste, and less chance of breathing in harmful fumes. Regulatory bodies and safety data back up these moves—with studies confirming reduced VOC emissions in labs using ionic liquids compared to classic petrochemical solvents.

Real Impact in Advanced Fields

Out on the edges of energy tech, 1-tetradecyl-2,3-dimethylimidazolium bromide plays a surprising part in battery research. Lithium-ion and other next-gen batteries sometimes use ionic liquids as electrolytes because they don’t catch fire as easily and offer better chemical stability. Scientists have documented steadier battery cycles and longer life when these salts are tailored right, lowering risks for everything from electric cars to power grid storage. The shift away from flammable, volatile organic solvents to ionic counterparts answers pressure from both regulators and the public for safer, more sustainable technology.

Challenges and Honest Answers

The story isn’t all glowing. These chemicals can get expensive, especially for larger-scale uses. Waste handling still asks for tight controls. Researchers have pushed for clearer long-term environmental studies, worried that some ionic liquids don’t break down so easily once they escape into waterways. Fact-driven choices call for honest comparisons between cleaner, safer handling and the full cost over a product’s life. At a minimum, safety training and proper disposal gear need as much investment as the compounds themselves.

Building Smarter Solutions

The science community puts energy into designing new types of ionic liquids, each tuned for safer, cheaper, or more effective performance. Open university research, government backing, and industry investment drive this field forward. The more honest conversation we have—balancing safety, cost, and long-term impact—the better off everyone is, from the person mixing up a reaction at a lab bench to families living downstream of a manufacturing plant. 1-tetradecyl-2,3-dimethylimidazolium bromide won’t remake the chemical world overnight, but its story shows why details matter.

Cracking the Code: The Molecular Formula

Step into a lab, speak with someone who works with ionic liquids, and chemists light up at long names like 1-Tetradecyl-2,3-Dimethylimidazolium Bromide. Strip away the jargon, and you’ll find a neat bit of molecular engineering. Here’s the core:

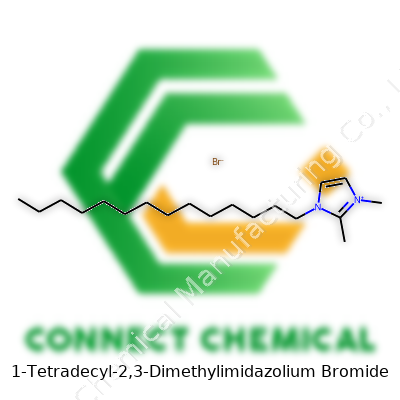

- Molecular formula: C19H37N2Br

This shows a molecule built from 19 carbon atoms, 37 hydrogens, two nitrogens, and a single bromine. That’s a handful, but the shape and arrangement matter as much as the numbers.

Structure: What’s Inside?

Imagine the molecule as two main components that stuck together. The “imidazolium” half is a five-membered ring holding two nitrogens across from each other. Both those nitrogens hang onto an extra methyl group, making the ring bulkier, less symmetrical than its parent. A long, straight chain—the tetradecyl part—hooks onto the “1” spot of that ring.

Finishing the picture, a bromide ion parks nearby. This isn’t held tight by covalent bonds; it floats close thanks to charge attraction. If you draw this out, the molecule sort of looks like a lollipop: the ring with its little methyl stubs as the head, the fourteen-carbon chain as the stick, the bromide ion off to the side, balancing the charge.

Real Value in Application

The world doesn’t just care about molecules for their own sake. Imidazolium-based ionic liquids, including this one, show surprising uses. Researchers like them for their tunable melting points and chemical stability. I once sat in on a synthesis seminar where the speaker, knee-deep in solvents and ionic compounds, explained how a small swap in the chain length or ring structure changes solubility or toxicity in a major way.

Take 1-Tetradecyl-2,3-Dimethylimidazolium Bromide to a beaker of water. It doesn’t mix easily. Toss it into an organic solvent, and it dissolves much better. That characteristic hints at its dual nature. Labs have found it especially handy for extraction processes: separating metals from waste streams, pulling out valuable catalysts, even cleaning up after chemical spills. Its thermal and electrochemical stabilities open doors in battery research and as an antimicrobial additive.

A handful of studies—one from Green Chemistry back in 2016—showed long-chain imidazolium salts can punch holes in bacterial membranes, shaking up pathogen management in healthcare and industry. Not every compound walks the line between chemical power and real-world usefulness. In a market hungry for greener chemistry and improved performance, molecules like this find space beyond the test tube.

Challenges and Ways Forward

Some folks worry about toxicity and biodegradability. Tweaking the ring or swapping out side chains can cut down on environmental persistence. Several startups now focus on tailoring these molecules so they break down more safely after use. Academic collaborations with industry groups push for new generations of ionic liquids—designed with life cycle from synthesis to disposal in mind.

The bottom line: 1-Tetradecyl-2,3-Dimethylimidazolium Bromide isn’t just a mouthful on a label; it’s a customizable tool for tackling today’s toughest chemistry problems. Understanding both the molecule and its structure lets us imagine better ways to use it and better ways to build the next generation.

Why Care About Storage?

Ask anyone who has handled specialty chemicals in a lab: careless storage can wreck research, spoil industrial batches, or even put people at risk. Compounds like 1-Tetradecyl-2,3-Dimethylimidazolium Bromide come with their own quirks. I’ve seen labs lose entire sample sets to moisture creeping into bottles, and I’ve watched new researchers beat themselves up after a container cracked under sunlight in a windowsill. With chemicals, small missteps quickly spiral into real headaches.

Keeping It Dry and Cool Isn’t Overkill

Walk through any reputable chemical storage room and you’ll spot the pattern. Most ionic liquids, including this one, break down quicker with heat, humidity, or sunlight in the picture. Exposing them shortens shelf life and can even create hazardous byproducts. Every reliable safety resource — from Sigma-Aldrich datasheets to university lab manuals — puts ‘store in a cool, dry place’ right at the top.

In practice, that means finding an area where temperature stays below 25°C and humidity doesn’t get out of hand. Fluctuating temperatures raise condensation risks, and nobody wants their chemical picking up water from the air. A typical chemical storage fridge works well, especially since it keeps light out too. I always recommend containers made of compatible, tight-sealing materials; glass is usually the standard, but high-grade plastics marked for chemical resistance can do the job too.

Keep It Labeled, Keep It Safe

More than once, I’ve seen an unmarked bottle become the source of rumors and confusion in a shared lab space. Clear labeling cuts through all that. Include the full chemical name, hazard codes, and the date received or opened. If someone needs to move quickly in an emergency, guesswork leads to mistakes. Everyone benefits from explicit instructions in plain sight. Storing your chemical in a lockable, ventilated cabinet minimizes risk, especially where inquisitive students or cleaning staff can stumble into the area. Consider secondary containment like trays or bins to catch leaks. Nobody enjoys tracking down a spill hiding in the back corner of a fridge.

Think Beyond Daily Use

Let’s not forget the long-haul. Many chemicals sit for years between order and disposal. Degradation isn’t always obvious until a project goes sideways or someone notices a strange smell. Reevaluate those old bottles every few months. Most manufacturers share stability data for their products. Lean on those details: they tell you how long the shelf life stretches under proper storage. If a batch hasn’t seen daylight in ages or shows color changes, crystallization, or clumps, don’t push your luck. Old, compromised material belongs in a waste container, not your next experiment.

Respecting the Hazards

1-Tetradecyl-2,3-Dimethylimidazolium Bromide isn’t the worst thing on the shelf, yet it carries some risks: skin and eye irritation, toxicity if ingested or inhaled. Gloves, goggles, and a lab coat aren’t optional. Accidental exposure almost always traces back to sloppy storage or handling. Lock in a habit of double-checking lids and secondary containers before you walk away. Ventilation stops fumes from building up — even low-toxicity compounds pose problems after long exposure. Teaching safe habits doesn’t just protect the current team; it passes know-how to newcomers, setting them up to avoid future close calls.

No Substitute for Common Sense

Some rules stay timeless: keep chemicals labeled, sealed, dry, cool, and out of reach when not in immediate use. Pay attention to expiration dates and warning signs, and consult the SDS if life throws you a curveball. I’ve watched good research thrive in spaces where everyone treats the storage of chemicals as part of the work, not an afterthought.

Respecting the Chemical’s Risks

Stepping into a lab with a compound like 1-Tetradecyl-2,3-Dimethylimidazolium Bromide, the first thing I remember from my own days in research is the sharp, almost instinctive attention to how little space there is between confidence and carelessness. This isn’t baking soda or table salt; it carries risks many overlook in a rush. The MSDS warns for a reason—some imidazolium salts act as irritants, and a substance with a long alkyl chain, like this one, sticks to skin and lingers in airways if handled wrong.

Basic Protection Tactics Matter More Than Fancy Gear

My own wardrobe for handling chemicals includes a properly buttoned lab coat, splash-resistant goggles, and nitrile gloves—never bare hands, never latex if I can avoid it. Long sleeves and closed shoes become as natural as breathing. In my experience, goggles and gloves get underestimated because people think accidents only happen to someone else. I once saw two drops splash onto a colleague’s wrist during what should have been a routine transfer. She scrubbed and rinsed until her skin turned red, and it still tingled for hours. No shortcut replaces careful preparation.

Aiming for Clean Air and Organized Spaces

Ventilation makes all the difference. Fume hoods belong to daily routine, not just to textbook recommendations. Some labs I’ve visited didn’t prioritize these basics—open windows, poor airflow, and the vague hope that a quick pour won’t release anything significant. Yet, even compounds without a strong smell can put stress on the body over time.

Disorganized benches lead to cross-contamination. I learned from a mentor to always double-check glassware for residue and only use freshly washed materials. It’s easy to assume the bottle’s clean, but leftover traces can start reactions or ruin months of data collection. Spills require immediate response. Standard sodium bicarbonate comes in handy for neutralizing acids, but for organic salts, absorbent spill pads and carefully scooped containment prevent tracking the compound into the next room.

Value in Habitual Checks

Before touching any container, I double-check the labels and seals. Too many labs wind up with unlabeled or poorly sealed bottles, which open doors for exposure or evaporation. Always having a clear waste-disposal plan in place, based on local regulations, protects both people and wastewater supplies. I’ve seen people dump small amounts down a sink, believing it "won’t matter," only for tests to show persistent contamination months later.

Preparation for Accidents and Long-Term Exposure

First aid kits need more than adhesive bandages. Keep an eye-wash station within arm’s reach and make sure everyone knows how to use it. I recall one instance where a quick rinse saved a colleague’s eyesight—something I don’t forget. Training newcomers builds a habit of respect and responsibility; I've seen productivity rise when everyone takes safety drills seriously.

Routine safety audits help spot small dangers before they escalate. I make a habit of reviewing my own handling steps each week and encourage that practice among peers. Chemicals like 1-Tetradecyl-2,3-Dimethylimidazolium Bromide may look unassuming, but the hidden risks require real vigilance.

Developing Safer Practices Together

It isn’t about fear—it's about building a culture where everyone looks out for their own health and that of those nearby. Sharing accurate information, focusing on the details, and running a tight ship with organization, cleanup, and emergency plans keeps accidents from happening. Respect for the substance, the process, and those walking the same halls will always outweigh the urge to cut corners or “just grab one more sample.” I’ve learned this the hard way, and it makes all the difference.

Breaking Down the Chemistry

Chemicals like 1-Tetradecyl-2,3-dimethylimidazolium bromide sometimes show up in research circles and specialty labs. On the surface, its long name hints at something complex, but its roots lie in the class of ionic liquids—substances with quirky solubility profiles. From my time working alongside bench chemists, I saw how experimenting with new solvents could unlock new syntheses or processing routes. Solubility defines the success or failure of an experiment more often than most realize.

Why Solubility Matters

Good research lives and dies by material compatibility. A compound that refuses to dissolve wastes time and money, especially if someone has invested in custom synthesis. I’ve seen chemists pace across labs when faced with batches that just “won’t go into solution.” That almost always leads back to the makeup of the molecule.

1-Tetradecyl-2,3-dimethylimidazolium bromide brings a puzzle. On one hand, it carries the imidazolium ring, which highlights ionic character. On the other, it sports a long tetradecyl tail—distinctly hydrophobic. Experience tells me that these structural pieces often create molecules that resist neat categorization.

Solubility in Water

Drawing on labs I’ve visited and published data, long alkyl chains attach themselves to ionic heads and usually drive the molecule out of water. While small imidazolium salts dissolve easily in water, tacking on a 14-carbon tail changes the game. The compound starts acting more like a surfactant—one end loves water, the other wants out. Sometimes, you see cloudy dispersions or micelles, not clear solutions. This behavior shows up in cleaning products and detergents too. Reading across the literature, reports confirm that 1-Tetradecyl-2,3-dimethylimidazolium bromide shows limited water solubility. It can disperse, but rarely achieves the clarity or total dissolution that true water-soluble salts promise.

Organic Solvents as the Better Option

Organic solvents like chloroform or acetone tend to do a better job dissolving molecules with extended hydrocarbon chains. My own work with imidazolium-based compounds backs this up. The rule of thumb in most labs: “like dissolves like.” The hydrophobic tetradecyl group finds comfort in organic environments. So, practical work favors using solvents like methanol, ethanol, or even non-polar options, provided the task does not demand strictly aqueous conditions.

There’s value in knowing your solvent mix. With solubility spanning a range, clever researchers often reach for cosolvent systems. Mixing water with a splash of alcohol can coax tough compounds into useful solution form. This approach sees action in pharmaceutical labs and materials science projects. Shake up your methods—sometimes small changes in solvent ratios make all the difference, based on firsthand experience in pilot trials.

Safety and Environmental Impact

Solubility questions stretch beyond the bench. Handling organic solvents triggers health and environmental considerations. Many industrial labs have nudged teams to limit use of harsh solvents in favor of greener, safer options. With a compound like 1-Tetradecyl-2,3-dimethylimidazolium bromide, formulating solutions in ethanol or other “greener” choices helps lower risk. Practical researchers weigh these decisions, often considering a solvent’s hazard profile as seriously as its dissolving power.

Looking for Solutions

For anyone navigating this solubility puzzle, remember what experience shows—testing a range of solvent options beats relying on a handbook listing. Document every trial, share results, and learn where the boundaries sit. Projects advance fastest when teams don’t assume—real observations trump expectations every time, and testing the boundaries of solubility has saved many promising efforts from hitting a dead end.