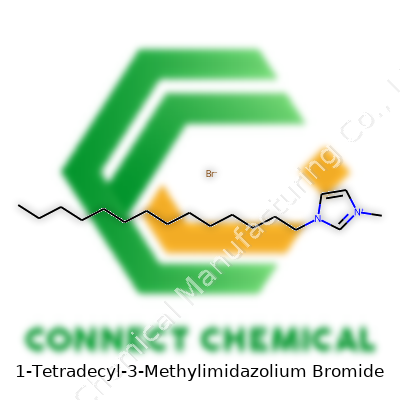

1-Tetradecyl-3-Methylimidazolium Bromide: Practical Insights and Real-World Uses

Historical Development

Not too long ago, chemists searched for salt-like substances that wouldn’t turn into crystals at room temperature. Ionic liquids like 1-Tetradecyl-3-Methylimidazolium Bromide came from this push. These molecules looked different—long alkyl tails, a charged core, and non-traditional properties. Through the 1990s and early 2000s, labs around the world started using versions of this compound to tackle old problems in greener ways. The development linked back to the steady move away from volatile organic solvents, hoping to cut down pollution in chemical plants and research facilities.

Product Overview

This compound shows up as a white or off-white powder, sometimes a wax depending on room temperature. Its structure brings together a methylimidazolium base with a big tetradecyl (C14) alkyl group, forming a large cation. The bromide anion rides along for charge balance. Commercial suppliers focus on purity, usually above 98%, since leftover reactants or water disrupt both lab and industrial tasks.

Physical & Chemical Properties

1-Tetradecyl-3-methylimidazolium bromide stays solid under typical indoor conditions and melts when warmed. Its molecular weight clocks in around 375 g/mol. The long hydrocarbon chain offers flexibility—dissolves well in alcohols but resists water, unlike most room-temperature salts. Thermal stability stands out: this material survives heating above 200 °C without breaking down quickly. It won’t catch fire like other organic chemicals, but long-term sunlight exposure may yellow the surface.

Technical Specifications & Labeling

Labels show the product’s chemical formula: C18H35N2Br, CAS registry number, date of manufacture, shelf life, and purity. Bulk quantities arrive in airtight drums or bags, usually with desiccants tucked inside. Typical analysis sheets include residual solvent levels, water content by Karl Fischer titration, and heavy metals. Some research labs print QR codes for instant tracking, tying back to a batch’s testing data.

Preparation Method

This material’s journey starts with a methylimidazole base and tetradecyl bromide. The chemist stirs these under nitrogen, heating the mix so the imidazole’s nitrogen attacks the bromide, kicking out a bromide ion and attaching the tetradecyl arm. Washing, recrystallization, and vacuum drying push unwanted leftovers off the product. This process avoids strong acids or bases, cutting down on tough-to-treat waste streams.

Chemical Reactions & Modifications

Chemists often tweak the imidazolium structure to change solubility, ion exchange ability, or even antibacterial effects. With a bromide counterion, swapping for another ion (chloride, nitrate, or an organic acid) comes by simple salt metathesis. The long alkyl chain opens doors for attaching catalytic nanoparticles, metal complexes, or dyes. Surface modification of silica or polymer beads with this salt turns ordinary materials into designer sorbents for water treatment or purification processes.

Synonyms & Product Names

You might recognize this compound under several trade or research names: [C14mim]Br, 1-methyl-3-tetradecylimidazolium bromide, or simply long-chain imidazolium bromide. Chem catalogs often shorten the name for clarity, and you’ll see it grouped under “ionic liquids” or “quaternary ammonium-like surfactants.”

Safety & Operational Standards

Handling always starts with gloves and goggles. Although less volatile than many lab solvents, the powder sticks to skin and dries it out. Inhalation risk climbs if you leave bottles open, so fume hoods keep things safe. Disposal doesn’t match the danger of chlorinated solvents, though local rules require dilution and slow incineration or chemical breakdown. Rimmed containers and regular cleaning help avoid sticky residue. Emergency plans stress prompt hand washing and eye irrigation after spills.

Application Area

People in my field tend to use this ionic liquid for specialty solvent blends, especially for difficult organic reactions. It lifts solubility for polar and nonpolar compounds at the same time—rare in ordinary solvents. Its surfactant traits help form stable emulsions, handy in drug delivery, cosmetics, or agrochemical additives. Water treatment engineers count on it as a phase-transfer catalyst, while chemists load it onto filters for capturing precious metals from mining streams. Electrochemists take advantage of its thermal stability in battery electrolyte experiments, hoping to extend charge cycles and cut down on flammable risks.

Research & Development

Universities push the envelope, trying to lower production costs and make greener synthesis. Research teams have checked its effect in enzyme stabilization, green extraction for natural products, and new materials for sensors. Some projects even turn to waste streams—recycling contaminated ionic liquid for repeated use in heavy metal capture saves disposal costs. Reports suggest swapping out the bromide counterion changes electrochemical properties, useful in fine-tuning for specific industrial steps.

Toxicity Research

Initial studies point out that 1-Tetradecyl-3-methylimidazolium bromide disrupts cell walls at high concentrations, especially in aquatic organisms. Its toxicity comes from the hydrophobic alkyl tail, which acts like commercial detergents and breaks up lipid membranes. Long-term studies haven’t yet nailed down its breakdown products in soil or water, so regulatory agencies call for prudent use and tight waste management. In my experience, the right protocols prevent most environmental releases, and spills rarely leave the lab bench. Still, the call grows louder for biodegradable versions or improved recycling schemes.

Future Prospects

This ionic liquid stands on solid ground in labs but faces big hurdles scaling up for industry. Sourcing renewable tetradecyl feedstocks could lighten the environmental footprint, and continuous-flow synthesis promises lower costs. If scientists manage to keep its useful properties while chopping toxicity and boosting recyclability, real breakthroughs will follow. The search for new counterions and hybrids with other surfactants and catalysts just kicked off. The work happening in pilot plants and startups right now might make today’s “niche” chemical tomorrow’s go-to solution for green chemistry and resource recovery.

Recognizing Molecules Beyond the Textbook

Simple formulas do more than fill up flashcards. Say the name “1-tetradecyl-3-methylimidazolium bromide” and most eyes glaze over. Chemists and anyone working in materials sciences know that behind every name and formula waits a real compound with real uses. The chemical formula of this compound is C18H37N2Br, which comes from the specific way atoms connect in its structure. That string of atoms holds the key to how it acts in labs and real-world applications, even if most people never see it outside a bottle with a big label.

What the Formula Tells Us

Looking at the formula, the “C18” means the backbone is built of carbon atoms — a whole bunch, considering it’s just one segment of a molecule. Imidazolium rings pop up a lot in ionic liquids, a group of chemicals that work as powerful solvents or electrolytes. The long “tetradecyl” tail, all fourteen carbons of it, makes the molecule less likely to dissolve in water but more likely to interact with fats, oils, or plastics. Chemistry, in this sense, moves into the practical. It’s not just numbers and formulas. The structure shapes real properties, and those properties push forward research into greener solvents, advanced batteries, or ways to break down pollutants.

Why Knowledge and Safety Count

Every time I worked in the lab, accurate chemical identification protected not only the experiment but my own health. The “Br” at the end stands for bromide — a halide ion that changes how the whole molecule behaves. With these ionic liquids, slip-ups can trigger unexpected reactions. Years ago, someone in my research group mixed a similar imidazolium salt with the wrong acid and wound up with a mess that was way harder to clean than they expected. These compounds are often touted as “green solvents” because they can replace more traditional, usually toxic ones. Still, calling something green doesn’t remove the need for training or careful handling, so a proper understanding of chemical formulas isn't just a trivia game—it prevents real dangers.

More than a Sum of Parts

Researchers keep pushing for alternatives to outdated, environmentally damaging chemicals. 1-tetradecyl-3-methylimidazolium bromide plays a part in that search, showing up in studies about extraction of metals from water or as a surfactant in new kinds of detergents. Its formula signals to chemists that trade-offs exist — molecules built for one eco-friendly purpose can turn out to linger in the environment, creating new challenges. Just swapping out an old solvent for an ionic liquid doesn’t solve every problem; the fate of the long carbon chain and its breakdown products matter just as much.

Pushing for Responsible Use and Innovation

Clear identification leads to safer labs, smarter regulation, and more responsible products. There’s a need for companies and researchers to share data about the persistence and toxicity of newer compounds, not just their technical strengths. Everyone who works with or creates new chemicals has a role to play, either by running transparency checks, sharing unexpected results, or exploring ways to recycle or safely destroy leftover materials. By looking closely at the chemical formula, both students and scientists tackle details that ripple out through research, the environment, and health systems everywhere.

Getting to Know This Chemical

1-Tetradecyl-3-Methylimidazolium Bromide has been on my radar since grad school for a good reason: it’s part of a class called ionic liquids. In the lab, this compound laughs in the face of volatile solvents and brings the kind of stability chemists crave. Thanks to its unique structure—long alkyl chain, imidazolium core, and bromide ion—it pops up often in academic journals and industry paperwork.

Key Spot: Green Solvent in Extra Tough Settings

Right now, industry keeps looking for cleaner technologies that cut down on waste and fire risk. Many folks in chemical manufacturing, from pharma to battery tech, use 1-Tetradecyl-3-Methylimidazolium Bromide as a so-called “green” solvent. Its low vapor pressure helps hold onto material during lengthy processes, which shrinks environmental impact. I’ve watched colleagues pull off tricky organic reactions that used to need high-waste, hazardous solvents—now they swap in this ionic liquid and scoop up comparable yields without toxic smells filling the room.

Role in Extraction and Separation

Mining and purification teams don’t always get enough credit. I saw firsthand, during a workshop on rare earth metals, that ionic liquids like this one have reorganized how researchers extract metals and valuable elements from messy mixtures. You can target specific components for recovery thanks to the customizable chemistry. The bromide ion gets replaced to catch or let go of precious ions as needed—fewer steps mean more efficient separations. Across some water treatment plants, you’ll spot specialists using it to remove organic pollutants from wastewater. The imidazolium part breaks up oily contaminants, making water safer to release.

Boosting Performance in Electrochemical Devices

Electrolytes shape how modern batteries and supercapacitors perform. This ionic liquid gets mixed into the next wave of energy storage devices. Its wide electrochemical window means more stable cycling, and that’s led to longer-lasting prototypes in several university labs. In fuel cells, the same property keeps the membranes from breaking down fast—especially at higher operating temperatures. From my time in an advanced energy course, hearing project partners swear by ionic liquids like this one convinced me they hold serious promise for energy storage.

Antimicrobial and Surface Science Innovations

Fighting bacteria safely on surfaces has dogged hospitals for decades. Recently, 1-Tetradecyl-3-Methylimidazolium Bromide found use as an antimicrobial coating. The imidazolium ring disrupts cell membranes of microbes without the timeout needed for older disinfectants. I’ve seen reports where medical device makers layered thin films of this ionic liquid on catheters to keep infections down. Cleaning crews don’t have to reapply harsh chemical wipes as often, stretching resources further.

What’s Next?

Every time I read an update on new eco-friendly catalysts or alternatives to everyday solvents, researchers mention ionic liquids like 1-Tetradecyl-3-Methylimidazolium Bromide. There’s healthy debate about long-term toxicity, especially if used at scale outside controlled labs. Still, thanks to its versatility and efficiency, many believe it’s shaping a smarter, safer way to manufacture—and clean up—across technology sectors.

Respect the Risks Before Opening the Container

Not all chemicals belong in backroom lockers or crowded supply shelves. 1-Tetradecyl-3-Methylimidazolium Bromide should never be left lying in the open or near heat sources. One experience from an early lab job comes to mind: A careless neighbor set down a sample next to a sunny window, and the sample began to degrade in less than a week. That kind of carelessness wastes money and time, and erodes trust in a lab’s safety culture. This chemical behaves best in a cool, dry, and well-ventilated location, away from any sources of light or heat.

Containers Matter More Than Most Expect

People often overlook the importance of the storage container. From my years spent in university and the private sector, I learned glass, amber bottles with snug-fitting, leak-proof caps outlast clear plastic with snap lids. The compound’s sensitivity to moisture and light calls for an opaque, chemical-resistant bottle. Long-term exposure to either air or humidity introduces unwanted changes. Not only can the compound break down, but the contaminating byproducts can create unpredictable behavior in later reactions.

Don’t Skimp on Labeling

Labels save lives, not just lab time. Permanent, unambiguous labeling avoids confusion. By writing CAS number, concentration, and date received or opened, you avoid the game of “guess the mystery jar.” Clear labeling helps keep storage rotation in check, reduces the risk of accidental mixing, and supports compliance if you ever face an inspection. On a regular basis, my colleagues and I caught mistakes early, simply because we actually read the date on the label.

Segregation Keeps Things Safer

Store 1-Tetradecyl-3-Methylimidazolium Bromide away from oxidizers, acids, or strong reducing agents. Too many accidents start with careless stock management. One incident in my early career involved a shared bench with mixed chemicals, and the resulting spill took hours to clean and cost plenty in lost samples. Dedicated chemical storage cabinets designed for organics often reduce this risk. These cabinets shield the box from accidental bumps, leaks, and the occasional clumsy neighbor.

Follow the Paperwork and Use a Chemical Inventory System

Companies and universities adopt chemical inventory systems for a reason. Tracking purchases, use, and disposal isn’t just about keeping records straight. It means outdated, degraded material doesn’t sneak into critical processes. I learned quickly to check materials in digital inventory before reaching for that old bottle. Regulators in many countries now require digital logs or paper trails, documenting every step from receipt to disposal. Sticking to these controls ensures nobody “forgets” about old chemicals collecting dust in the back corner.

Spill Kits and PPE: No Place for Shortcuts

Personal protective equipment saves nerves as much as lives. Gloves, goggles, and a clean, dedicated workspace cut risk to a minimum. Always keep spill kits nearby, because even careful handling won’t prevent every mistake. In my own work, missing a spill kit caused more panic—and cleanup—than necessary. Read the SDS for 1-Tetradecyl-3-Methylimidazolium Bromide before working, and always use the buddy system for unfamiliar compounds.

Understanding the Real Risks

1-Tetradecyl-3-Methylimidazolium Bromide isn’t found on the shelf at the local hardware store, and I remember the first time I handled it during a research project. Its use serves specific industrial and lab processes, but any substance with an imidazolium core means safety isn’t just a checkbox—it's mandatory. This compound brings hazards: skin irritation, eye damage, and serious issues with inhalation or accidental ingestion.

Why Personal Protection Matters

Once, I witnessed a careless grad student pipette this chemical without gloves. He shrugged off the warning—until his hands started burning minutes later. The lesson still sticks: chemical-resistant gloves form the first barrier between skin and danger. Nitrile gloves work far better than latex or vinyl. Eye protection also isn’t negotiable; one splash leads to hours in the emergency room. Well-fitted goggles shield eyes from aerosols or accidental spurts.

Good Air Saves Lungs

A friend of mine ran an experiment using a fume hood. Afterward, she shared how the distinct smell caught her attention even there. Poor ventilation invites exposure. I always check for working extraction fans before opening any bottle, especially with volatile or powdered chemicals like this one. Air handling systems do more than remove smells—they move potential toxins away from breathing zones.

Respecting the Label

Keeping 1-Tetradecyl-3-Methylimidazolium Bromide in the right container stops accidental mixing or spills. Most labs require labeled, sealed bottles and spill-proof trays. During a hectic afternoon in a teaching lab, someone ignored the rule, and a spill followed. We spent an hour cleaning up and filling reports. Those labels and secondary containers save time, safety, and money all at once.

The Truth about Cleanup

Using this compound outside a fume hood once ended in a messy spill on a shared bench. Sand or spill control materials soaked it up, but the contaminated material could never end up in regular trash. All disposals, from gloves to wipes, needed waste bags for hazardous chemicals. Skipping this step means real harm—direct exposure to custodial staff or contamination in the community.

Training Makes a Difference

During yearly safety refreshers, the stories of close calls drive home the need for proper training. Even the most experienced lab workers admit to mistakes after growing too familiar with routine. Anyone working with 1-Tetradecyl-3-Methylimidazolium Bromide benefits from refresher courses— how to use eye washes, emergency showers, and how much time matters after exposure.

Good Habits Build Security

A single mistake can leave lasting damage. Every time I see a new batch come in, I check the safety data sheet again. Over the years, these simple habits—armor-like gloves, tight caps, trusted airflow, prompt cleanup, and clear labeling—shaped much safer labs. No shortcuts. As industry knowledge grows, keeping up with safety recommendations is the surest way to send everyone home healthy.

Getting the Real Story on Solubility

Scientists and engineers want answers that cut through jargon. With 1-Tetradecyl-3-Methylimidazolium Bromide—usually known in the lab as a “long-chain imidazolium salt”—the big question is always solubility. Can you dissolve it in water? What about common organic solvents? The answer shapes everything from mixing to cleaning up spills.

Peering at the Structure: What It Tells Us

Look at the compound: a bulky tetradecyl group tacked onto an imidazolium core, paired with a bromide anion. The long chain acts oily and resists mixing with water, but the imidazolium part grabs onto water molecules. You get a push-pull dynamic that quickly reminds any chemist of their first confusing ionic liquid experiment.

Water: The Tough Sell

Imidazolium salts with short chains like methyl or ethyl dissolve easily in water—no surprise, since they act more like regular salts. Lengthen the alkyl to tetradecyl, and it’s like trying to blend oil with vinegar. I’ve seen 1-Tetradecyl-3-Methylimidazolium Bromide clump and separate in water, forming micelles if the concentration gets high enough.

One study published in Journal of Solution Chemistry measured its water solubility and found a sharp drop once the alkyl chain reaches twelve carbons or more. At room temperature, its water solubility drops below 0.1 mol/L, and getting it to dissolve takes a lot of stirring—plus patience. That lines up with what most industrial chemists see in practice. In pure water, it barely budges into solution, except at tiny concentrations where micelles start to form.

Organic Solvents: More Willing Hosts

Once organic solvents come into play, the story shifts. Solvents like ethanol, methanol, chloroform, and acetone welcome compounds with long alkyl chains. The polar imidazolium head group stops things from acting totally hydrophobic, but the tail fits best in less polar environments. In a teaching lab, I’ve mixed 1-Tetradecyl-3-Methylimidazolium Bromide into ethanol with little fuss. It dissolves much faster, and you don’t see the frustrating cloudiness that haunts water solutions.

Researchers in green chemistry have harnessed this trait for solvent selection. Organic solvents offer higher concentrations and stable dispersions. As a bonus, separating products from these media uses less energy than water-based extractions, sidestepping some environmental headaches.

Why It Matters for Green Science and Industry

The solubility profile of 1-Tetradecyl-3-Methylimidazolium Bromide explains a lot about its role in modern labs and factories. Ionic liquids often claim “greener” profiles, but a lipophilic version like this poses unique waste problems—water treatment becomes trickier if it doesn't dissolve nicely. Managing spills or rinsing equipment can sometimes require loads of organic solvent, which adds cost and potential hazards.

Sustainability teams looking for safer reagents now ask for data on solubility and environmental persistence. We know long-chain imidazolium salts hang around in the environment, sometimes building up in plants and microorganisms. Better information-sharing between chemical manufacturers and end-users could spark new options: shorter chain analogues for water-based work or biodegradable variants for organic applications. Teams already experiment with blending short-chain and long-chain salts for fine-tuned solubility, offering a path to solutions that work both in the lab and out in the world.

Towards Smarter Choices

1-Tetradecyl-3-Methylimidazolium Bromide resists dissolving in water and behaves much better in organic solvents. Every chemist has their own “tried and true” approach, but transparency about real-world behavior helps researchers, teachers, and industrial teams make informed, safer, and greener choices.