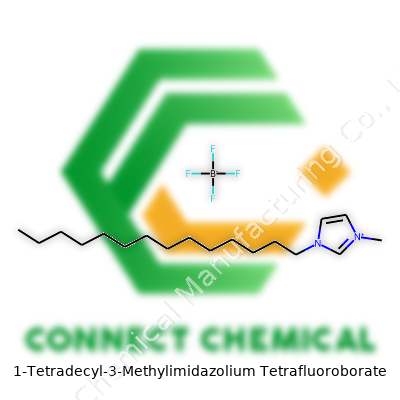

1-Tetradecyl-3-Methylimidazolium Tetrafluoroborate: An In-Depth Commentary

Historical Development

Chemists have sought liquids that could serve as alternatives to volatile organic compounds for decades, both to drive greener chemistry and to push the boundaries of materials science. Room-temperature ionic liquids, like 1-Tetradecyl-3-methylimidazolium tetrafluoroborate, stepped into this space in the 1990s, promising low vapor pressure and a chance to tune solvents for specific jobs. In the early stages, research groups across Europe and Asia focused on imidazolium-based ionic liquids due to their relative stability and customizable structures. This compound came from a wave of efforts aiming for longer alkyl chains on the imidazolium ring, targeting better solubility in nonpolar environments and greater ability to interact with organic substrates in synthetic reactions. Its adoption stretched from university labs to scaled-up pilot plants, where researchers noticed improved efficiency in processes like biphasic catalysis and separations. Academic journals recorded a sharp uptick in studies on ionic liquids by 2005, with this compound steadily making its way into both textbook discussions and patent filings.

Product Overview

1-Tetradecyl-3-methylimidazolium tetrafluoroborate, sometimes written as [C14mim][BF4], brings a long hydrocarbon chain together with a tetrafluoroborate anion. The long alkyl tail, compared with analogous ionic liquids with shorter chains, means this compound behaves differently when dealing with oils, polymers, and certain solid surfaces. Its structure puts it on the radar for use in extraction, catalysis, and lubrication—areas where researchers keep an eye out for stability under harsh conditions and compatibility with nonpolar solvents. In the marketplace, manufacturers offer it as a colorless or slightly yellow oily liquid, packaged under inert gas and shipped in sealed bottles to protect it from moisture. The price remains higher than traditional solvents, but the benefits in tailored applications often outweigh the costs for specialty uses in research and advanced manufacturing.

Physical & Chemical Properties

Physically, this ionic liquid stays liquid well below room temperature and resists volatilization even under vacuum. Users encounter a substance with a viscosity a bit higher than water—thick, but manageable with standard pipettes or syringes. Its melting point usually stays below 0°C, while the decomposition temperature tends to hover around 300°C, which provides breathing room for handling under standard laboratory conditions. The compound refuses to dissolve easily in water, thanks to its long hydrocarbon chain, but mixes well with nonpolar solvents, setting it apart from its shorter-chained relatives. Electrical conductivity, though lower than some pyridinium analogs, still suffices for electrochemical work. Chemically, it holds up against hydrolysis but will show signs of degradation if exposed to strong acids or bases for hours. Flammability stays low, as with most ionic liquids, but the tetrafluoroborate anion necessitates caution at high temperatures: breakdown may release corrosive species like hydrogen fluoride.

Technical Specifications & Labeling

Bottles arrive labeled with details like the CAS number (174899-83-3), molecular formula (C18H35BF4N2), and batch-specific purity, which typically exceeds 98%. Labs and suppliers stress moisture control, since water uptake can alter physical properties and affect outcomes in sensitive experiments. Some packaging includes water content by Karl Fischer titration, giving assurance for those working in analytical or moisture-sensitive syntheses. Material safety data sheets list the compound’s physical description, recommended storage temperature, emergency procedures, and regulatory status—vital information for users from bench chemists to shipping departments. Orders from reputable producers supply batch analytics, including NMR and mass spectrometry results, which avoids guesswork and supports traceability from shipment to shelf.

Preparation Method

The preparation often kicks off with a quaternization reaction. Methylimidazole reacts with 1-bromotetradecane in the presence of a suitable base, usually in polar aprotic solvents, to form the cationic species. After purification—often by repeated washing and sometimes column chromatography—researchers bring in sodium or potassium tetrafluoroborate in an aqueous solution. The desired product drops out as two phases form, aided by the nonpolar chains crowding the interface. Scientists separate the bottom ionic liquid layer, dry it meticulously under vacuum, and test for free halide and water to confirm purity. Some groups have scaled this up for pilot production, using techniques from organic chemistry and fine-tuning for shorter reaction times and higher yields. Greener approaches now use less solvent, leverage microwave irradiation, or swap conventional reagents for more benign alternatives, without sacrificing the product’s integrity.

Chemical Reactions & Modifications

Beyond synthesis, researchers modify this ionic liquid for a range of applications. The untapped imidazolium ring allows for further functionalization, introducing sulfates or phosphonates to tailor solubility, surface activity, or catalytic function. It can host metal ions for catalysis or serve as a support medium for nanoparticles, leading to systems with unique selectivities in organic transformations. Esterification and alkylation of the N3 position happen under mild conditions, giving birth to ionic liquid analogues that serve specific industrial goals. The tetrafluoroborate anion, though relatively inert, sometimes swaps out for less toxic or more biodegradable partners, by simple anion metathesis with salts like sodium acetate or potassium thiocyanate. Researchers check these modifications rigorously for stability, looking at both bench-top performance and longevity during weeks of operation.

Synonyms & Product Names

The compound appears in literature and catalogs under several names, including 1-tetradecyl-3-methylimidazolium tetrafluoroborate, [C14mim][BF4], and less commonly, N-methyl-N-tetradecylimidazolium tetrafluoroborate. Manufacturers often shorten these to C14mimBF4 or C14IMBF4, depending on their labeling conventions. Regardless of the name, consistent purity and handling rules apply across brands, from major suppliers to boutique chemical vendors. Researchers navigating literature or databases use these synonyms to avoid confusion and to access as much technical data as possible.

Safety & Operational Standards

Direct handling of ionic liquids calls for attention to detail. Spills, while less likely to evaporate, still pose hazards to skin and eyes, so standard PPE (gloves, lab coats, goggles) stays non-negotiable. Some guidelines, especially those used in European labs, require work in ventilated spaces due to possible anion breakdown and trace impurities. Waste disposal involves segregating ionic liquids from halogenated and non-halogenated solvents; sending them to incineration rather than aqueous streams. Ongoing debates focus on the environmental persistence of both the cation and the tetrafluoroborate anion, which triggers extra scrutiny in downstream disposal. Many manufacturers work toward transparency, supplying detailed safety data and instructions for neutralizing spills with absorbent materials and basic clean-up reagents.

Application Area

Real-world uses for this compound cover organic synthesis, separation processes, and electrochemical systems. Chemists handling phase-transfer catalysis prize the long alkyl chain, since it helps extract nonpolar products from complex mixtures. Some engineers use it as a lubricant or anti-static additive in specialty plastics, playing off its stability and resistance to oxidation. In the lab, its use in biphasic systems increases rates of certain palladium- or ruthenium-catalyzed reactions by holding both catalyst and substrate in a shared solvent cage. Pharmacological researchers sometimes leverage it as a membrane mimic or to dissolve stubborn APIs for screening studies, opening new routes for drug discovery. Others explore it in dye-sensitized solar cells and batteries, since the low vapor pressure and robust ion conductivity help beat the hazards seen in more volatile electrolytes.

Research & Development

Ongoing research digs deeper into structure–function relationships. Changing chain length, ring substituents, or anion type lets scientists fine-tune nearly every property, from viscosity to toxicity. Recent years have produced hybrid materials by anchoring the cations onto solid supports like silica or carbon nanotubes. Some teams use computational modeling to predict how new analogues will behave in separation or catalysis. This arms them with data before heading into the lab and speeds up the discovery process by orders of magnitude. Researchers share findings through open-access databases, which builds community knowledge and helps avoid duplicative efforts a few years down the line. Industry consortia invest heavily to test large libraries of ionic liquids in green chemistry applications, working toward safer, more sustainable industrial processes.

Toxicity Research

Compared with traditional solvents, this compound shows moderate biotoxicity—it rarely kills aquatic organisms outright but can stunt growth and disrupt enzymatic activity even at low concentrations. The long alkyl chain, which boosts performance in some settings, also increases the likelihood of persistence in soils and bioaccumulation in organism tissues. Studies using zebrafish, green algae, and Daphnia show chronic exposure affects reproduction and development, raising red flags for environmental release. The tetrafluoroborate anion brings its own baggage, since breakdown in the environment or under acidic conditions may produce fluoride ions, which pose risks to both aquatic life and drinking water. Leading journals cover a steady stream of work on substituting the anion or capping the alkyl chain length to cut toxicity, without giving up the chemical versatility that drives adoption. Regulatory agencies follow these trends closely, and new products often undergo tiered toxicity screening before use in large-scale production.

Future Prospects

The future for 1-Tetradecyl-3-methylimidazolium tetrafluoroborate rests on expanding applications and smarter, greener synthesis. Scientists seek ways to lower costs through recycled feedstocks or continuous processing, while industry icons look to overcome toxicity hurdles with safer, biodegradable versions. In energy storage and conversion, rapid developments in battery electrolytes draw on the compound’s stability under high voltage, which outpaces many early ionic liquids. The road ahead also includes tougher scrutiny from regulators, particularly in Europe and East Asia, where environmental limits tighten each year. Transparent reporting, open-source toxicity data, and strong ties between academic and industrial groups will determine how widely the compound sees use outside specialty research. For now, research continues to drive new applications in the lab, while responsible stewardship steers its use toward lasting, sustainable progress.

Research and Lab Bench Uses

Walk into almost any materials science lab and you’ll see racks of ionic liquids, each filling a niche. 1-Tetradecyl-3-methylimidazolium tetrafluoroborate often sits right among them. It stands out for its stability and neat, almost slippery handling properties. Chemists love this compound because it brings low volatility—no vapor clouds in the room—even at elevated temperatures. In synthesis work, it offers a smooth environment for chemical reactions that need a steady, non-flammable medium. With its long hydrophobic tail, this liquid helps dissolve nonpolar organics. Graduate students chasing tough conversions sometimes swap out old-school volatile organics for this ionic liquid and find yields going up.

Electrochemistry and Energy Storage

Batteries don’t stay the same for long. In the hunt for safer electrolytes, researchers steer clear of liquids that catch fire. Here, 1-tetradecyl-3-methylimidazolium tetrafluoroborate catches attention. Its ionic nature allows movement of charge, and it doesn’t act up under voltage stress. It enables smoother cycling and longer battery life, especially in experimental lithium and sodium cells. If you’ve kept up with literature, you’ll see it tested in supercapacitors too. Its window of stability helps supercaps charge and discharge rapidly without breaking down, unlike some short-chain alternates.

Industrial Catalysis and Green Chemistry

Factories push for cleaner processes. Old solvents clog up the environmental reports and cost too much to recycle. This imidazolium salt brings a low-toxicity profile and a knack for dissolving stubborn compounds. It partners up with catalysts, sometimes even acting as a catalyst itself. Take alkylation or transesterification—both grind forward better in this ionic environment. Less hazardous waste comes out the other end. My own research group used it for biomass conversions, and the reaction cleanup felt almost easy compared to petroleum-based liquids.

Analysis and Extraction Techniques

Sample prep in the lab, especially liquid-liquid extraction, often turns into a hunt for the right solvent. With 1-tetradecyl-3-methylimidazolium tetrafluoroborate, analysts isolate tough-to-extract organics without pulling in so much water. This means less interference and clearer analytics. Chromatographers sometimes run their instruments quieter, seeing cleaner baselines and fewer mystery peaks. It can also act as a so-called “task-specific” liquid, with small tweaks letting it soak up specific pollutants or metals.

Nanomaterials and Coatings

Moving into nanotech, stability and controlled growth count for a lot. Scientists use this ionic liquid to make metal nanoparticles or carbon-based materials with narrow size distributions. The compound acts not just as a solvent, but as a sort of shaping agent, pushing the particles to grow evenly. In coatings, it creates films that resist moisture and even cuts down on microbial growth. Personal experience prepping nanoparticles taught me good results often come from using these longer-chain ionic liquids—the yield improves, and the particles come out more uniform.

Environmental Impacts and Safer Alternatives

Questions do come up about the environmental fate of these chemicals. Tetrafluoroborate anions don’t break down easily, so long-term studies matter. Some companies already invest in recycling programs for spent ionic liquids instead of dumping them. I’ve seen research into tweaking the imidazolium core, hoping for better biodegradability in the next generation. Until then, its lower flammability and disposability offer an edge over plenty of volatile organic solvents.

Making Sense of Chemical Purity

Purity tells us how much of a specific substance is present, without the clutter of unwanted materials or contaminants. In chemistry, nothing wastes money and time like working with a product that’s not up to spec. Labs, factories, and even schools can face real setbacks from a simple mix-up over purity. I once ran a high school experiment that failed, only to learn the iron filings we used contained rust and dirt. Our test for oxidation flopped, the whole class left confused, and the teacher caught flak from the science fair committee.

People place value on purity because small contaminants can change reactions, harm health, or break equipment. Pharmaceuticals work only if they contain what’s printed on the bottle; the difference between life-saving medicine and a useless pill can come down to fractions of a percentage point. Food companies check for purity for similar reasons. No one wants to ingest something laced with heavy metals or forgotten cleaning agents, as history has shown through ample food recalls and even poisonings.

Breaking Down Chemical Grades

Chemical grade tells buyers what jobs a substance can handle. Labels like “reagent grade,” “laboratory grade,” and “technical grade” work as signals. Higher grades suit critical lab work—think medical research or pharmaceuticals—where even trace contamination can throw off data or endanger health. Lower grades often go to industrial work, water treatment, or cleaning agents, where precision isn’t the point and minor impurities won’t ruin the end product.

Grades aren’t marketing fluff; they come from standard-setting groups, such as the American Chemical Society (ACS) or the U.S. Pharmacopeia. These organizations test and publish requirements so labs around the world speak the same language. Hospitals, for example, can trust “USP grade” to mean something because it meets rigorous testing. This kind of trust forms the backbone of clean research and reliable manufacturing.

Why Every Buyer Needs to Ask

Failing to ask about purity or grade opens the door to real risk. I recall seeing a production line grind to a halt because technical grade sodium hydroxide, meant for drain cleaning, mistakenly made its way into a batch of soap. The result was soap that irritated skin and put the brand’s reputation on the chopping block. That day, the company learned that chemical grade isn’t a detail to skip, no matter the pressure.

In laboratory projects, a single impure sample corrupts results, wastes money, and throws timelines. When you buy chemicals online or from a broker, clear labeling on certificates and packaging means you have a shot at meeting safety standards, avoiding product recalls, or even criminal investigations.

Building Better Supply Chains

Companies can push for transparency by only buying from suppliers who share certificates of analysis and test results. Regular audits and checks—sometimes a pain—protect reputations in the long run. Using checklists before each shipment arrives quickly weeds out errors. In one organization I worked for, each delivery included a quick purity spot-test. Over two years, this step paid off by catching a mislabeled drum the distributor hadn’t realized was off-spec.

For anyone, from researchers to engineers and teachers, learning to read purity and grade fosters a culture of care. Accurate records, communication between buyers and sellers, and up-to-date staff training can stop small mistakes from turning into disasters. Purity and grade labels build trust at every step—between coworkers, businesses, and the public at large.

Why Storage Matters for Lab Work

Anyone who’s spent a chunk of time in a lab knows that even a bottle of fine white powder can become a headache if mistreated. 1-Tetradecyl-3-methylimidazolium tetrafluoroborate, a mouthful to pronounce and a mainstay in ionic liquid research, shows this truth daily. My colleagues once took shortcuts on chemical storage “just for a weekend”—cleanup chewed up half the week. Proper conditions keep datasets clean, budgets in check, and people out of the eye-watering, fume-filled aisles of bad surprises.

Moisture is the Silent Enemy

This chemical hates water. Seriously. Even a bit of humidity turns it from predictable and stable to something else entirely. As an ionic liquid, it attracts moisture from the air fast. The slightest exposure causes hydrolysis, where its structure breaks, which then throws off its melting point and might change its behavior in experiments. Just last year, a shipment stored in a damp storeroom showed traces of decomposition. The supervisor shrugged, but replacing the order cost four figures and delayed every related project.

Warm and Bright: Two Storage No-Nos

Direct sunlight and heat speed up chemical changes. The structure of imidazolium salts, in general, handles normal room temperatures, so I always keep mine in the lab fridge at around 4°C. Cooler is better, as this slows down reactions with airborne contaminants. Avoiding windows seems like a small thing, but a colleague once stored a clear bottle near a window, and UV rays triggered a slow breakdown. That error nearly ruined a month’s work in materials science testing.

What Actually Works

I store bottles of 1-tetradecyl-3-methylimidazolium tetrafluoroborate in tightly sealed, amber glass containers. Those help block out stray UV. My lab uses high-quality desiccators filled with silica gel for hygroscopic compounds. I try to minimize air exposure: new bottle gets opened, sample measured quickly, then cap goes on tight. If I have to leave it out, I wrap the container with parafilm and keep it away from solvent vapors and heat sources.

Labeling is Not Just for Show

A legible label with name, concentration, and date means fewer storage mistakes. I date every bottle, and for anything older than six months, I retest purity before critical work. Simple, but I’ve seen labs throw out whole lots because nobody remembered when a batch arrived or how long it sat open.

Reducing Spoilage and Risks

Cleanliness pays dividends. Spills of this salt feel greasy and hard to mop up, so I keep storage areas uncluttered and enforce a strict “no food, no drinks” rule. Proper ventilation prevents inhaling dust, which can irritate airways. Regular checks of seals, fridges, and desiccators help stop tiny leaks from turning into big problems.

Building Good Habits—For Safety and Science

Once, someone in my group ignored these rules. Contaminated salt led to weird peaks in their spectra and invalidated a big part of their thesis. It’s tempting to rush, but safe, careful storage saves more time—and research cash—than shortcuts ever will. Science thrives on reliability, and reliability starts with how we treat the tools we count on.

Everyday Items Can Surprise You

It’s easy to feel confident picking up a product off a shelf. Most labels give us a pretty good idea of what’s inside, but sometimes, danger hides behind familiar packaging. Not everyone stops to think that a thing as common as paint remover or a household cleaner can carry real risk. I remember walking past a shelf of cleaning agents in a supermarket a few years ago—the kind you use without much thought. A container had leaked, and the harsh smell made my eyes sting. That’s not something you forget quickly.

What Makes a Product Hazardous?

Many products in daily life contain chemicals that pose risks to health and the environment. Take bleach. A go-to for disinfecting, but combine it with ammonia, and you’ll soon get toxic fumes no one wants to breathe. Even beauty products can trip us up. Nail polish remover often uses acetone, which burns fast and evaporates in the air—too much in a closed room, and you’ll notice a headache coming on.

Why It Matters to Check Labels

The small print gives you the real warnings. A red diamond sign tells you something’s flammable or corrosive. Laws make companies include these signs for good reason: even a quick splash can send you to the emergency room. Instead of tossing old paint thinner with the trash, you face special disposal at a local site—regular landfill just won’t do. Every year, news stories show what happens when pool cleaners mix the wrong way or children get hold of colorful detergent pods. One mistake transforms an everyday task into a hospital trip.

My Experience With Workplace Safety

I spent some summers working in a warehouse, moving boxes of pool chemicals. No one let us touch them until we had a training session about what spilled chlorine gas does to lungs or how water alone could start a fire. The lesson stuck with me: trust the hazard symbols and wear gloves, goggles—anything protective. Even people who keep a tidy garage at home might not realize a split battery or old can of bug spray needs more care than the regular trash.

How You Can Stay Safe

Products come with instructions and hazard warnings for a reason. If it says “keep away from children,” that rule counts even if you don’t have kids running around. Use protective gear for anything strong enough to burn, corrode, or ignite. Ventilation matters; fumes build up fast. Don’t improvise by mixing chemicals. For leftover paints, solvents, or old electronics, find your community’s disposal guidelines—some towns offer collection days for exactly this reason.

Rely on Credible Resources

Staying informed means listening to the experts. Groups like the Centers for Disease Control, Environmental Protection Agency, and your local fire department publish facts about chemical safety and product handling. Over time, I’ve learned to check the Safety Data Sheet for every unfamiliar product—a few minutes now is better than hours at an urgent care later. Live by the advice: treat every label and warning with respect. Surround yourself with the right information and take every warning seriously—you’ll prevent accidents before they happen.

Why the CAS Number Matters

A chemical’s identity means everything in research and industry. CAS numbers work like fingerprints, helping avoid mix-ups or confusion with similar molecules. For 1-tetradecyl-3-methylimidazolium tetrafluoroborate, the CAS number is 799276-30-9. You plug this into a database or catalog, and there’s no doubt about which substance you’re getting. This specificity helps scientists and technicians handle chemicals safely, check regulations, order supplies, and track inventory.

Chasing a chemical with a slightly different name or formula wastes time and blows budgets. In my time working on lab projects, an order placed using a typo in a CAS number led to weeks of setback and piles of paperwork. Accuracy streamlines work and keeps mistakes at bay.

Weighing in: The Molecular Weight

The molecular weight, or molar mass, sets the stage for nearly every practical use of a compound. For 1-tetradecyl-3-methylimidazolium tetrafluoroborate, the molecular weight lands at 395.43 g/mol. Every calculation in solution preparation, reaction engineering, or analytical chemistry returns to this number.

Years ago, prepping a solution for a catalysis experiment, I relied on this type of information to hit the right concentration. Too much or too little could mean lost resources or dodgy results. At scale, miscalculating molecular weight turns into costly waste and safety risks. For labs and manufacturers, precision means money, time, and safety.

What’s in a Name (and Weight)?

Names like 1-tetradecyl-3-methylimidazolium tetrafluoroborate get scientists excited for more than their tongue-twisting structure. This ionic liquid doesn’t evaporate easily, resists most solvents, and works in extreme chemical environments. Biochemists have started looking at ionic liquids as greener options to old school solvents. Reports show some are less toxic and easier to recycle, though not all ionic liquids play nice with the environment. Every legitimate source—Sigma-Aldrich, PubChem, chemical safety boards—relies on referencing CAS numbers to avoid ambiguity with isomers and cousins in the same chemical family.

Every day, researchers check papers, patents, and online forums to see if this molecule pushes performance in batteries, electrochemistry, or bioseparations. Getting facts right about CAS number and molar mass helps the entire chain. One mistake can snowball. Having the right number and molecular weight makes compliance with safety protocols easier. Regulators and auditors consult trusted data, and companies stay clear of fines and rework.

Building Confidence with Reliable Data

The right chemical data draws a line between hunches and hard evidence. Following well-curated resources and staying up-to-date with trusted databases gives professionals an edge. Honesty about sources and rigorous cross-checking back up trust with numbers. Everyone from new students to experienced chemists knows that a single digit can shift safety, waste, and project outcomes.

It’s tempting to copy figures from an online list or a colleague’s notebook. In chemical science, cutting corners leads to setbacks. I’ve seen corrective actions roll out company-wide after a small database error. Fact-based work habits—using the CAS number 799276-30-9 and molecular weight 395.43 g/mol for 1-tetradecyl-3-methylimidazolium tetrafluoroborate—offer security and efficiency, but also help build a culture of responsibility that keeps people and processes on the right track.