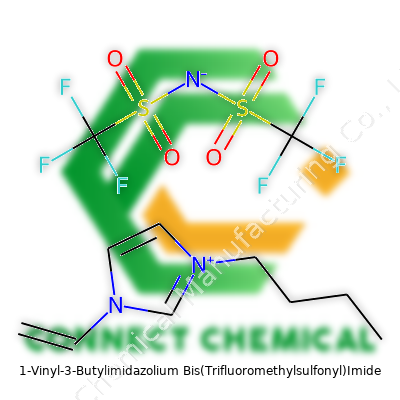

1-Vinyl-3-Butylimidazolium Bis(Trifluoromethylsulfonyl)Imide: A Deep Dive

Historical Development

Back in the early 2000s, the chemical industry watched a new class of substances step out of the lab’s shadow and into broader industrial use: ionic liquids. Among them, 1-vinyl-3-butylimidazolium bis(trifluoromethylsulfonyl)imide, often abbreviated as [VBIM][NTf2], emerged as a workhorse for researchers. The trail started with simple imidazolium salts, but the introduction of vinyl and butyl groups opened up new possibilities for task-specific ionic liquids. Early patents and open literature tell a story of persistent fine-tuning, responding to industry frustration over volatile organic solvents. Tinkering with the imidazolium scaffold and anion pairing soon delivered a liquid that handled higher temperatures and harsher chemicals. Each round of modifications came from chemists committed not just to synthesis, but also to pushing for safer, more sustainable lab practices across academia and the corporate sector.

Product Overview

1-Vinyl-3-butylimidazolium bis(trifluoromethylsulfonyl)imide sits on benches as a pale, viscous liquid. In practice, it gives researchers and manufacturers a way to avoid flammable organic solvents. Its defining features stem from the imidazolium core, which imparts stability, and the bis(trifluoromethylsulfonyl)imide anion that keeps it fluid even at subzero temperatures. Chemists reach for it when they need a solvent that resists decomposition, even in the face of strong bases or acids. The molecule’s vinyl functionality also allows it to interlock with other chemicals and form new materials under controlled conditions.

Physical & Chemical Properties

From firsthand lab experience, [VBIM][NTf2] impresses with a melting point far below room temperature, often hovering around minus 10°C. Its density reaches approximately 1.4 g/cm³, giving a reassuring heft in the flask. Water doesn’t play nicely; the liquid’s hydrophobic anion keeps moisture at arm’s length, often evidenced by a ready phase separation when mixing with aqueous systems. Researchers gain a noticeable edge in electrochemistry thanks to the wide electrochemical window—up to 5 volts without degradation. It handles temperatures above 200°C before showing signs of breakdown, and the chemical’s high ionic conductivity keeps processes running smoothly in electrochemical cells and polymerizations.

Technical Specifications & Labeling

Manufacturers typically label [VBIM][NTf2] by its purity, frequently reporting values above 97%. Information about water content, often below 0.1%, appears as well. I remember double-checking the chemical’s CAS number at every order since proper identification prevents costly mix-ups. Bottle labels in institutional labs outline critical safety notices, such as the necessity for gloves and goggles, given its potential toxicity and skin permeability. Some suppliers include electrochemical data and viscosity details, which helps to match the product with targeted experiments in advanced battery research and catalysis.

Preparation Method

Lab synthesis follows a methodical series of steps. Start by quaternizing 1-vinylimidazole with 1-butyl bromide, yielding the corresponding imidazolium bromide salt. The product then undergoes anion exchange, often with lithium bis(trifluoromethanesulfonyl)imide in aqueous phase. Stirring vigorously, the mixture soon separates into organic and aqueous layers. The resulting ionic liquid gets washed and dried using high vacuum or molecular sieves to pull out residual water. The vinyl group endures intact through the process, offering a point of further modification down the road. Years spent preparing batches taught me that contamination from old glassware can spike water content, so clean conditions matter at every step.

Chemical Reactions & Modifications

The vinyl functionality on the imidazolium ring doesn’t just sit for show. Polymer chemists exploit it, initiating free-radical polymerization to build polyelectrolytes or crosslinked materials that carry ionic liquid properties throughout a much larger structure. The cation can also participate in substitution or addition reactions, creating new ionic liquids with tailored properties for sensors or separation science. The NTf2 anion resists nucleophilic and electrophilic attacks, so it keeps its shape through harsh conditions, keeping the base ionic liquid framework strong whether in advanced batteries, catalytic media, or high-temperature lubricants.

Synonyms & Product Names

Across catalogs and publications, the compound turns up under a parade of names. 1-vinyl-3-butylimidazolium bis(trifluoromethylsulfonyl)imide surfaces most often, but shortened forms like VBIM NTf2 or [VBIM][NTf2] creep in, especially in technical discussions. Some suppliers swap in the anion’s alternative label—bis(trifluoromethylsulfonyl)azanide—confusing anyone not tuned in to IUPAC conventions. In academic writing, clarity carries the day, since standardized nomenclature sidesteps supply chain miscommunication or costly errors in experimental setup.

Safety & Operational Standards

Direct handling of this ionic liquid brings a risk of skin absorption and eye irritation, warnings that dot safety data sheets and labels. Its relatively low volatility cuts down on inhalation risk, but splash and spill incidents in the lab reinforce the value of basic PPE: gloves, eye protection, and lab coats. Disposal proves tricky, as the NTf2 anion’s stability means waste streams linger longer in the environment unless incinerated at high temperature. During my own years supervising students and staff, I insisted on glovebox manipulation for any open operations, and waste drums earned their place beneath the fume hood, not simply in the sink or trash.

Application Area

Manufacturing and research sectors value this ionic liquid for its solvent strength and thermal stability. Electrochemistry stands out—lithium batteries and advanced supercapacitors need precisely this combination. The liquid’s broad window of electrochemical stability improves energy storage without risk of early breakdown. Separation science and polymer chemistry also draw on its tunable solubility and compatibility with radical processes. Pharmaceutical research dives in, polymerizing the vinyl group into ionic polymers that serve as drug carriers or membrane materials. Catalysis researchers report marked rate boosts and selectivity shifts when using [VBIM][NTf2] instead of more traditional solvents.

Research & Development

University labs and R&D groups keep pushing boundaries with [VBIM][NTf2]. New data emerge on embedding the ionic liquid into composite membranes and gels for next-generation fuel cells. Advanced manufacturing harnesses the liquid’s ability to dissolve lignocellulosic biomass, opening a path to produce biofuels or specialty chemicals from renewable sources. Collaborations between battery startups and academic labs continually turn to this liquid when chasing more stable electrolytes for carbon-neutral energy systems. Open-source research databases now list hundreds of studies on molecular tweaks or process optimization for this and related ionic liquids.

Toxicity Research

Despite low volatility, toxicity can’t be shrugged off. Studies suggest moderate aquatic toxicity stemming from the fluorinated sulfonyl anion. Some reports note bioaccumulation risks in fish and invertebrates. In the lab, rats exposed to high doses display signs of organ stress, especially in liver and kidney function markers. This isn’t a household product, and unrestricted release into water tables or soil spells trouble long term. Environmental chemists call for better disposal methods, perhaps through catalytic destruction of the NTf2 moiety or improvement in recovery and recycling rates. Carefully tracking exposure, documenting spills, and maintaining well-documented health and safety protocols stand among the most practical responses to these issues.

Future Prospects

The future of [VBIM][NTf2] rides on two tracks: sustainability and new application frontiers. Work continues on greener synthesis strategies, moving away from halogenated solvents and pursuing recycling routes that fit into closed-loop manufacturing. Scientists focus on lowering toxicity, either by swapping in less persistent anions or engineering cations that degrade more easily. Opportunities remain bright in energy storage, pharmaceutical polymer matrices, and environmentally responsible catalysis. The balance of performance, stability, and safety will steer further breakthroughs, and the next generation of materials chemists faces the challenge of scaling up these advances while treating safety and sustainability as twin priorities, not afterthoughts.

Electrolytes in Next-Gen Batteries

Batteries make the world go. Electric cars grab headlines, but the hidden challenge often sits inside: keeping batteries safe and stable while pushing energy limits. I’ve watched researchers wrestling with the usual suspects—flammable liquids, unstable separators, leaky systems. 1-Vinyl-3-butylimidazolium bis(trifluoromethylsulfonyl)imide, a mouthful known by its abbreviation [VBIm][TFSI], steps in with a big value: it keeps batteries cool under pressure and resists breaking down at high voltages. Lithium-ion and even sodium batteries gain new life with this stuff. A safer battery means more trust from folks who hesitate to park an electric vehicle in their garage or bring home big battery packs for solar setups.

Green Chemistry Turns a Corner

Chemical industries looking to clean up their act are giving [VBIm][TFSI] a second look. Traditional solvents give off fumes, catch fire, and pollute local water. This particular ionic liquid remains stable, doesn’t evaporate, and allows for smart recycling of precious metals and specialty chemicals. As someone who’s spilled solvents in the lab, the idea of replacing them with an option that barely stirs the air feels like a big environmental win. It allows metal plating with much lower pollution, and pharmaceutical operations can sometimes skip entire cleanup steps because everything stays locked in the liquid. Companies want to tick boxes on green credentials, but the switch doesn’t stick unless solutions like this actually work in day-to-day operations.

Advanced Materials and Polymers

I’ve seen engineers get excited about tailoring plastics and coatings. They often reach for ionic liquids as additives or as part of new polymer chains. [VBIm][TFSI] earns fans for its stability and ability to tweak conductivity. Add a pinch to a plastic mix and you can coat circuit boards that shrug off moisture and resist dust. You get sensors for medical patches that keep sending signals even if sweat or rain hits them. Teams working on next-gen flexible phones use it as a way to lower static and keep displays working longer. There’s a lot of hope surrounding durable, long-lasting materials, and a stable additive helps them actually deliver on those promises.

Catalysis and Synthesis: Speed with Precision

Catalysts drive reactions faster. Some ionic liquids end up poisoning a process or gunking up precious equipment. [VBIm][TFSI] brings a rare mix of chemical muscle and a gentle touch. Researchers find it especially useful for tough reactions, where water or regular acids break things apart or leave impurities. I remember reading about chemists running stubborn transformations in only a few hours, soaking up valuable products right from the reaction. That step alone can slash the time between an idea and a product, leading to actual manufactured goods, not just lab papers.

What Comes Next?

No technology grows in a vacuum. Every new material calls for updates to safety protocols and better supply routes. Universities and private labs keep looking for new niches, and they’re hungry for replacements that work well but cut the risks. If we want progress in batteries, fewer toxic spills, and cheaper production for electronics, it’s worth following compounds like [VBIm][TFSI]. Not because they’re trendy, but because they solve real headaches for those working on the front lines of science and industry.

Real-World Lessons From the Lab

People don’t always think about risk until it’s staring them in the face. In college, I volunteered during a community chemistry demo, stirring up oohs and ahhs with beakers and colored flames. That moment burned a memory into my mind—one simple mistake can turn a boring demo into an emergency. Not every chemical is as dramatic as sodium in water, but every bottle comes with a story of things gone wrong. I started reading every label and Material Safety Data Sheet (MSDS), and encouraged classmates to do the same. You can’t guess your way through chemical safety and hope for the best.

PPE: No Room for Shortcuts

A lot of folks want to skip gloves or goggles, thinking, “I’ve handled this stuff for years.” Unfortunately, chemical splashes don’t care how much experience someone claims. Even familiar chemicals, like bleach or acetone, can cause burns or knock you out with fumes in a stuffy room. Nitrile gloves, safety glasses, and long sleeves are the frontline defense—nothing flashy, just proven tools. I remember dragging a sleeve across a bench with sulfuric acid residue and watching a pinhole burn right through. Small mistakes happen fast and it’s easy to think you’ll see the hazard before it hits, but you don’t.

Ventilation Makes a Difference

Opening a window or working near a fume hood isn’t busywork. Chemicals like ammonia, formaldehyde, or strong cleaning products give off vapors that can build up, even if you don’t smell them. Headaches and dizziness are usually blamed on a skipped meal or bad coffee, but I’ve seen people walk out for air and never come back. Make sure air is flowing; check that anything with fumes—organic solvents, acids—or fine powders stays contained. Don’t trust a fan in the corner—real fume hoods and extractor fans change outcomes.

Labeling and Storage: The Homework You Never Skip

People laugh about “the unlabeled bottle” sitting in the fridge, but it isn’t a joke once you realize some chemicals react dangerously if mixed together. Stuff as common as hydrogen peroxide and acetone deserves a clear label. The disaster stories—wrong bottle, wrong shelf, unexpected reaction—tend to involve shortcuts with labels. Keeping acids separate from bases, oxidizers away from organic solvents, and never leaving reactive stuff out in the open aren’t just best practices, they keep people out of harm’s way.

Spills and Disposal: More Than a Mop and a Drain

Cleaning up a spill won’t work with paper towels or a regular mop. For strong acids or flammable liquids, absorbent pads and neutralizers are essential. Tossing chemicals down the drain lands people in trouble with the sewer system, and can harm fish and water treatment systems. The city health department where I grew up came out hard against backyard labs—somebody thought pouring copper sulfate down the drain wouldn’t matter and turned the water blue for a whole block. Check local rules on hazardous waste pickup, and never assume it’s someone else’s job.

Don’t Wing It—Check the Guide

Manufacturers include safety instructions for a reason. Read the guide, even if it’s been years. Keep a copy of emergency contacts and spill procedures taped up near the work area. Fire extinguishers and first aid kits are a must. The goal: nobody gets hurt, and everyone goes home healthy. We owe it to ourselves—and everyone around us—to treat every chemical with respect and a bit of caution born from hard experience.

Unpacking the Basics

Ask any chemist about the most critical question before starting an experiment, and the answer often points to the molecular formula and the structure of a compound. Every compound’s properties draw straight from the way atoms hook together and the number of each chemical present. If the setup has a faulty formula or structure, the rest starts to fall apart—lab experiments, large-scale synthesis, or drug development.

Why Formulas and Structure Shape Everything

Long before molecules show off their traits, their formula lays down the rules. For instance, glucose and fructose share the same formula, C6H12O6, but react and taste very differently due to their structural arrangement. This fact always serves up a lesson in school labs and industry settings. A subtle shift in how atoms connect can turn a bland sugar into a life-saving medication or a hazardous substance.

A classic story that stuck with me happened with a team trying to synthesize a pesticide. The target compound contained only one extra oxygen atom compared to another—both looked almost the same on paper. Mixing them up could have wiped out more than the intended insects. Knowing the correct structure and formula made the entire difference.

Impacts on Safety and Innovation

Chemical manufacturing and pharmaceuticals don’t play around with these details. Take aspirin—its simple formula, C9H8O4, doesn’t impress on its own, but the structure dictates pain alleviation. Alter one bond, and the effect changes or vanishes. Every time a new compound lands in development, teams lean on analytical techniques like NMR, IR spectroscopy, and X-ray crystallography to nail the formula and layout. It’s not just academic; regulatory agencies expect airtight paperwork backed by solid evidence.

Ignoring proper identification of chemical structure causes dangerous side effects or recalls. For example, a misidentified contaminant once led to a costly pharmaceutical recall that harmed brand trust. It drove home the point for me that the tiniest misstep in structure or formula can ripple through people’s lives and pocketbooks.

Solutions and Ways Forward

Analytical chemistry keeps giving fresh tools to pin down structures. Years ago, we only had basic titrations or melting point checks. Now, a single run through a mass spectrometer can provide atomic weights and suggest possible compositions. At the same time, computer modeling lets chemists predict how atoms might arrange before making a single batch. Collaboration across science fields helps double-check results and weed out errors.

Training also needs to focus on real-life hands-on examples. Textbooks can’t substitute for taking a compound from synthesis to full characterization. I’ve found lab apprentices grasp structure best by sketching out molecules and cross-referencing analytical readouts. Science thrives on curiosity, but it stands on clear structure and formula.

Final Thoughts on Precision

Getting a molecular formula and structure right is far more than memorizing symbols. It marks the difference between progress and setback, safety and disaster. Anyone working with chemicals owes the world their commitment to accuracy—one misplaced atom changes everything.

Lessons from Handling Unfamiliar Chemicals

Every bottle with a tongue-twisting name on its label deserves scrutiny, especially liquids like 1-Vinyl-3-Butylimidazolium Bis(Trifluoromethylsulfonyl)Imide. Even seasoned chemists catch themselves double-checking the quirks of ionic liquids before putting them on the shelf. In my years of lab work, forgetting the simple details—temperature, light, and exposure to air—has caused more hassle than big, dramatic accidents. This chemical, often called an IL, might look stable, but ignoring its storage needs brings plenty of trouble.

Sensitivity to Air and Moisture

One big problem with many ionic liquids comes from their tendency to draw in water from air. I once left a similar IL in an open beaker on the bench for half a shift. By the end, it had gotten tacky and diluted itself by pulling in moisture. 1-Vinyl-3-Butylimidazolium Bis(Trifluoromethylsulfonyl)Imide isn't any different. Water can affect chemical performance and even tamper with polymerization. After such slip-ups, I started using tightly sealed bottles with special valve tops. Storing it in a dry box with a desiccant—think fresh silica gel packets—works well for anyone without fancy gloveboxes.

Temperature Control: Why Refrigeration Makes Sense

Friends in the organic synthesis community usually keep these bottles cool, often in refrigerators. I've seen what happens when labs get warm in summer: bottle contents degrade faster and sometimes even leak pressure. Room temperature sometimes seems fine, but cooler temperatures slow down unwanted reactions. For this particular compound, a temperature between 2°C and 8°C keeps it fresher, especially over long periods. Just keep it away from food—nobody wants to mix up chemicals with lunch.

Light Exposure and Color Changes

Certain ionic liquids lose integrity under direct sunlight. I've seen clear samples turn yellowish in sunlit windows—sometimes this means nothing, but often it's a warning sign of slow, sneaky decomposition. Opaque bottles or storage away from windows and UV sources help, even if the degradation looks only cosmetic. Store this IL in amber glass or a thick-walled plastic to block most light.

Labeling and Shelf Life: Lessons Learned the Hard Way

One bad habit in busy labs comes from sloppy labeling. I've fished out old reagent bottles with unreadable dates more than once. A simple label with open-date, source, and handling notes saves guesswork months later. Keep older stock in front to use before it ages. Some labs handle ionic liquids in such small amounts that even a single spill or mislabeling ruins an entire project.

Handling Spills and Hygiene

Even careful handling sometimes fails. Spills dry into sticky, almost invisible films on benchtops. Use gloves, goggles, and if there's a mess, wipe up with isopropanol and paper towels right away. Washing hands afterwards isn’t just protocol; these liquids can linger on skin unnoticed and move from one surface to another. If your workspace runs with strict chemical hygiene, these mistakes rarely escalate.

Steps for Smarter Storage

Don’t just toss a bottle on the shelf and hope for the best. Keep this ionic liquid sealed in dry, cool, dark places. Store away from acids, strong bases, and strong oxidizers—combining the wrong bottles leads to hazardous reactions. Use good labeling and track your inventory, learning from small slipups before they become real troubles. In the chemistry world, investing in dry boxes and proper PPE pays off, both for safety and long-term project reliability.

Testing the Waters with Ionic Liquids

Curiosity hits fast after reading about ionic liquids taking center stage in labs and industry. These unique chemicals show up across batteries, cleaners, and green chemistry. But before mixing them up with everyday solvents or putting them inside familiar hardware, it’s worth stopping and thinking. A promising formula on paper often runs into trouble once solvents, tubing, glass, or surfaces come into play.

Real World Experience Always Teaches

Back in a university lab, I learned early that not everything plays nice together. Chemicals that looked promising on the shelf sometimes corroded plastic, clouded glass, or turned solutions into thick soup. A mentor once showed me a bottle of ionic liquid that had eaten through a standard cap after a week. Surprising at first, but really it’s the hard reality of mixing chemicals: compatibility makes or breaks any process, and sometimes you don’t spot trouble until cleanup time.

Why Compatibility Checks Matter

Mixing ionic liquids with common organic solvents like ethanol or acetone may look harmless in a beaker. Reality throws in surprises. Some ionic liquids can leach plasticizers from bottles, attack rubber seals, or change structure if exposed to certain solvents. Problems pop up fast in electrochemistry setups, where a seemingly small reaction ruins expensive equipment.

Most safety incidents around ionic liquids come from poor awareness of what touches what. In 2022, a report brought up how an ionic liquid mixed with water-based solvents reacted with PVC tubing in a pilot plant, shutting everything down and forcing a part replacement. Simple mistakes with materials can ruin months of work.

Knowing Your Materials

People often assume glassware handles anything. Not always. Ionic liquids with halide groups sometimes etch or stain glass. Polymers like polypropylene usually survive, but others such as polystyrene or PVC turn brittle or gooey around aggressive salts. Stainless steel holds up against many ionic liquids. Aluminum doesn’t. Even seals and gaskets can dissolve away unless they’re made from PTFE or high-grade Viton.

As for solvents, solubility looks good in published tables—up to a point. Research out of Germany last year showed some ionic liquids resist mixing with typical lab solvents, forming awkward-looking layers and lowering efficiency of reactions. Once you know the liquid’s ions, you can often predict which solvents become tricky or which materials last. No shortcut beats a basic spot test or running a small trial batch first.

Moving Past Trial and Error

Manufacturers have started sharing larger compatibility charts as ionic liquids pick up attention. The American Chemical Society puts out updated lists comparing stress on elastomers, pipes, and container types. A few companies test their new ionic liquid formulas across popular materials, narrowing down safe choices for engineers and chemists. Plenty of labs share these results online, but always double-check details for your specific formula instead of trusting a broad generalization.

Compatibility questions might sound boring at first, but they protect budgets, health, and safety. Every chemist stares down the question, “Is this a smart mix?” Testing that question—by reading up, running a trial, and documenting changes—almost always pays off better than salvaging messes later. Safe, successful work sits on the shoulders of preparation.