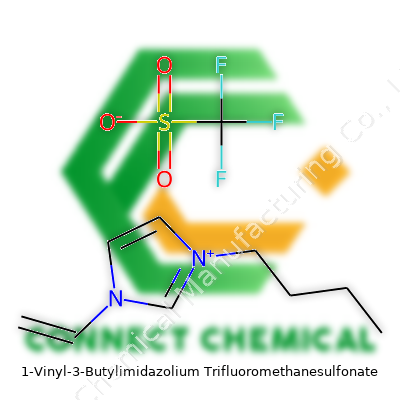

1-Vinyl-3-Butylimidazolium Trifluoromethanesulfonate: Progress, Properties, and Prospects

Historical Development

The history of imidazolium-based ionic liquids, including 1-vinyl-3-butylimidazolium trifluoromethanesulfonate, traces back to early interests in safer, more adaptable solvents in the late 20th century. Researchers wanted alternatives to volatile organic compounds found in many chemical processes. Chemists noticed that imidazolium salts offered stability and unique solvation abilities, so they dove into structural variations. From college labs to industrial reactors, development moved quickly in the 1990s once their physical robustness and low vapor pressure became obvious. Trifluoromethanesulfonate anion, or triflate, brought another level of chemical resilience, and pairing it with the vinyl functionalized cation created new application opportunities in electrochemistry and organic synthesis. Every step in its development came from practical aims: safety, ease of use, improving efficiencies, and pushing towards greener chemistry.

Product Overview

1-Vinyl-3-butylimidazolium trifluoromethanesulfonate, often listed under product names like [VBIM][OTf], stands as a versatile ionic liquid, notable for its excellent conductivity, wide liquid range, and strong thermal stability. Strong covalent coordination in its structure makes it less prone to decomposition under common laboratory conditions. Scientists choose this salt for polymerization media, electrochemical devices, and as solvents that don’t evaporate or explode under heat. Commercial suppliers package the product in sealed amber bottles, prepared for experimental repeatability in research, offering options in various purities, most often above 98%. Its popularity rests not only in its inherent properties but also the support from existing scholarly references, safety documentation, and proven compatibility with demanding synthesis.

Physical & Chemical Properties

1-Vinyl-3-butylimidazolium trifluoromethanesulfonate looks like a colorless to pale yellow liquid at room temperature. Its viscosity stands higher than typical solvents, so pours seem syrupy and it tends to coat glassware. The ionic strength brings a density well above that of water, often in the range of 1.2–1.3 g/cm³. Its boiling point stretches above 300°C, far beyond most organic compounds, giving it superb thermal resilience. Solubility proves interesting: it mixes easily with common polar solvents and can handle a surprising range of organic molecules. Chemically, the vinyl group remains reactive, making it possible to tether the imidazolium core to other substances through copolymerization or related reactions. The triflate anion supports strong ionic conductivity, bolsters its chemical resistance, and helps keep the overall product inert to moisture or air.

Technical Specifications & Labeling

Suppliers usually specify 1-vinyl-3-butylimidazolium trifluoromethanesulfonate with tight controls on water content, color, and trace metals. Water remains below 1% for most research grades. Iron, copper, and other transition metals fall under 10 ppm in certified lots. Labels include batch number, manufacture date, shelf-life, manufacturer, and country of origin, along with hazard and precaution statements in line with the Globally Harmonized System (GHS). Clear warnings about eye and skin contact, instructions for safe handling, and guidance on use in well-ventilated spaces form part of standardized labels. These technical standards come from years of close calls and real-world mishaps in both lab and production settings. Tight specs save time and lab resources by reducing the odds of unexpected interactions with experimental systems.

Preparation Method

Synthesis of 1-vinyl-3-butylimidazolium trifluoromethanesulfonate often starts with quaternization of 1-vinylimidazole with butyl bromide, yielding the corresponding bromide salt. Purified salt then undergoes metathesis reaction with sodium trifluoromethanesulfonate. Extraction and careful filtration separate the desired ionic liquid from byproducts and excess reagents. Quality relies on washing steps to remove unreacted halides and strict temperature control throughout, since overheating can degrade the vinyl group or the imidazole core. Recrystallization and vacuum drying refine the product for analytical and preparative chemistry work. Each process step has been shaped by experience, balancing yield with purity, and the best teams often develop their own tweaks to save time on workups.

Chemical Reactions & Modifications

The reactive vinyl group built into 1-vinyl-3-butylimidazolium salts opens the door to further functionalization. Polymer chemists use it for radical polymerizations, linking the imidazolium moiety into polymer matrices that add ionic conductivity or antimicrobial properties. Cross-linking reactions build gels and membranes for advanced separation or battery technologies. Modification often means swapping the triflate anion for others through ion exchange, smoothing compatibility with new substrates or tuning electrochemical window. Researchers have tested use as a template in sol-gel reactions, letting it act as a porogen or structure-directing agent. Transformation relies on the robust, but still reactive, nature of this salt’s molecular structure. Laboratories return to this cation-anion pairing because of its reliability under the strain of both high heat and active chemical environments.

Synonyms & Product Names

1-Vinyl-3-butylimidazolium trifluoromethanesulfonate rolls out under several names: [VBIM][OTf], 3-butyl-1-vinylimidazolium triflate, and 1-vinyl-3-butylimidazolium trifluoromethanesulphonate. Trade catalogs sometimes list it as VBuIm OTf, and synonyms can move between papers as researchers build on each other’s work. Standardization gained steam in recent years with IUPAC and CAS Registry stepping in. Product codes on vials, though hard to decipher sometimes, let buyers trace each batch back through the supply chain for quality assurance. As research expands, these names serve as anchors in a sea of ever-more-diverse imidazolium derivatives.

Safety & Operational Standards

Even substances tagged “green” or non-volatile deserve real respect, and that’s the case here. Users expect information about handling precautions, splash protection, safe storage, and what to do in case of accidental spills or body exposure. GHS hazard codes flag irritating potential to skin and eyes, and procedures for safe waste disposal match regular chemical lab best practices. Training covers not just the direct use, but how to manage glassware cleaning and spill kits, too. Facilities keep emergency eyewash stations and ventilation fans on at all times when transferring or stirring. Nobody wants to cut corners with chemicals, and continuous safety training reflects lessons passed down from old accidents and near-misses. Institutional review boards and regulatory bodies take a keen interest as industrial volumes rise. Sharing in peer networks about safe use and mishap response pushes the science forward and keeps labs running.

Application Area

This ionic liquid lives in many research corners. Electrochemists prize its broad electrochemical window for use in supercapacitors and advanced batteries, leveraging both its stability and high ionic mobility. In catalysis, it reduces volatility losses and enables more exact temperature control. Polymer scientists employ it as a co-monomer or dopant, enhancing conductivity in fuel cell membranes or anti-static coatings. Organic synthesis relies on its solvent power, especially when reactions call for high boiling and stable yet nonflammable media. Analytical chemists run it in sample preparations and separations where water or typical solvents just won’t work. Industrial engineers pay attention where phasing out hazardous organic solvents isn’t optional. Research hospitals and pharmaceutical companies test it for use in separation and drug formulation, taking advantage of non-reactivity and high purity. Seeing its use grow in environmental labs and even green chemistry classrooms underlines its staying power as a safer alternative to traditional reagents.

Research & Development

Research with this ionic liquid often dives into its polymerization potential, as the vinyl functionality hooks into a broad set of copolymerization schemes. Investigations extend to applications in lithium batteries, where stable cycling and ionic conductivity over many recharge cycles stand as hard requirements. Groups test its effect in homogeneous and heterogeneous catalysis, examining selectivity and yield. Efforts in environmental cleanup explore its potential as a reusable extraction medium, targeting metals and organic pollutants that resist simpler approaches. The intersection of materials science and ionic liquid chemistry often brings unexpected results, like new ionogels or novel antimicrobial films. Experienced researchers learn early on to tune processing conditions—dryer solvents, purer reagents, tighter controls on temperature—to get the most reproducible results. Collaboration across chemistry, engineering, and applied sciences means innovations appear not only in journals, but in patent filings and conference proceedings. Real progress unfolds in the lab bench grind of characterization, data analysis, and incremental reproducibility.

Toxicity Research

Toxicology investigations show 1-vinyl-3-butylimidazolium trifluoromethanesulfonate carries lower volatility and less acute inhalation risk than many traditional solvents, though skin and eye irritation risk persists. Studies in zebrafish and cultured mammalian cells suggest moderate cytotoxicity at high exposure, especially from the triflate anion. Real concern comes with repeated or chronic exposures, underscoring the need for gloves, fume extraction, and prompt cleanup of spills. Some reports note gradual bioaccumulation, so responsible disposal and containment practices matter. Manufacturers work with independent laboratories to keep up with regulations and new findings. The long tail of environmental data continues to expand, especially as production scales up. For those of us working in the lab, these findings translate to never getting complacent—a lesson stressed during every safety refresher and in every chemical hygiene plan.

Future Prospects

1-Vinyl-3-butylimidazolium trifluoromethanesulfonate stands out as more than a research curiosity. Demand rises for reliable ionic liquids as batteries, capacitors, and green synthesis ramp up in tech and industry. As university and commercial partnerships dig into solid-state electrolytes and recyclable catalysts, the vinyl group’s tunability draws in new interest. Advances in additive manufacturing and printed electronics push for materials with adjustable conductivity and processing ease, opening even more doors. Environmental sustainability drives scrutiny of both production and end-of-life disposal. New synthetic pathways under development seek to cut waste, lower costs, and deliver even higher-purity material, all evidence that the chemical community pays attention to E-E-A-T principles. Researchers expect to see more work on biological interactions, long-term ecotoxicity, and life-cycle analyses. Many scientists believe that the intersection of safety, performance, and environmental impact will shape both laboratory and commercial uses far into the next decade.

Why Scientists Gravitate Toward Ionic Liquids

Chemistry can feel like magic until a closer look reveals the choices that drive modern labs. 1-Vinyl-3-butylimidazolium trifluoromethanesulfonate stands out for a few big reasons. This compound falls into a group called ionic liquids – liquids that don’t evaporate like water, resist catching fire, and remain stable across large temperature swings. These features are why researchers started experimenting with ionic liquids as green alternatives to toxic or volatile solvents.

Electrochemistry: Batteries Built to Last

Every year, new phones, electric cars, and laptops hit the shelves. Promises of better battery life and safety often follow. That’s not possible without safe, strong electrolytes. This is one arena where 1-vinyl-3-butylimidazolium trifluoromethanesulfonate finds its value. Electrolytes let electrical current move between a battery’s electrodes. Most batteries use flammable solvents that limit performance and safety. In my experience watching colleagues hunt for flame-resistant options, ionic liquids grabbed their attention. Tests show this ionic liquid doesn't catch fire, so batteries built with it face less risk of sudden failures.

Growing Role in Organic Synthesis

Organic chemists rely on solvents to drive or speed up reactions. Over the years, discussions around cleaner processes have taken center stage. I remember attending a chemistry conference where one group showed how using this compound as a reaction medium allowed for cleaner separation and higher yields. This means less hazardous waste and easier recycling of reaction mixtures. Its unique structure lends itself to dissolving many organic and inorganic compounds, setting up reactions that bog down in water or petroleum solvents.

Polymer Science: Bringing in Flexibility and Conductivity

From flexible phone screens to smart windows, polymer science leans heavily on new materials. Incorporating 1-vinyl-3-butylimidazolium trifluoromethanesulfonate into polymers brings in ionic conductivity and flexibility. I’ve watched postdocs use it to prepare polymer electrolytes for fuel cells and capacitors. These polymer blends work at room temperature, carry ions efficiently, and survive demanding mechanical stress. In comparison, older materials break down faster. This ionic liquid also laughs off moisture and doesn’t freeze easily, so real-world tech can work in humid or cold climates without hiccups.

Cleaner Metal Production and Extraction

Mining rarely gets labeled as “clean,” yet greener practices do exist. Extraction and refining of metals like copper, nickel, or rare earth elements is easier and safer using ionic liquids as extractants and electrolytes. In pilot studies, this imidazolium-based triflate outperformed traditional acids and solvents. Colleagues working with rare earths tell me the waste stream shrinks and worker safety rises, since fumes and spills carry less risk. This trickles down to less harmful byproducts, less energy consumption, and simpler recycling of extraction fluids.

Environmental Ties and Future Solutions

Every advantage comes with a catch. Disposal and potential toxicity must stay front of mind. Some reports raise concerns about persistence in water or soils, so better biodegradability data will help regulators and industry leaders make smart calls. Transparent reporting, careful waste management, and continued investment in environmental research can safeguard against backfires as demand grows.

By stepping up in batteries, organic synthesis, polymers, and mining, 1-vinyl-3-butylimidazolium trifluoromethanesulfonate pushes chemistry away from risky old habits. As tech moves forward, staying honest about the full impact of new materials will keep progress steady and responsible.

Purity Grades Shape Results

Products like chemicals, supplements, or specialty ingredients always come with a catch: purity matters. If you’ve ever handled raw materials in a lab, mixed chemicals for a small business, or tried to source high-quality supplements for a clinic, you already know the trouble that comes from choosing the wrong grade. Impurities might ruin batches, cause health risks, and even land your organization in hot water if there’s a recall. Not all products are equal—nor are they meant to be.

Different Grades, Different Uses

Every industry sets its own standards. Pharmaceutical companies reach for the highest purity grades—the kind that get scrutinized by regulators and auditors. Even tiny impurities can affect safety or change how a drug works. Food producers and supplement brands need to keep contaminants at levels safe for the public but they don’t always spring for “pharma” grade, since rigorous purification hits the wallet hard. Technical and industrial sectors often go with cost efficiency, using grades that tolerate minor contaminants—nobody needs ultra-pure solvents to clean machine parts, for example.

Labs and research centers jump between grades depending on the work at hand. Academic research may allow for some flexibility, while clinical trials demand tighter controls. I’ve seen the stress that comes from failing a quality audit because a cheap batch was picked over a verified, tested grade. People often overlook that documentation—every certificate, every analysis—is just as important as the product itself.

Purity Impacts Safety and Performance

People focus on cost, but performance and safety follow purity. Toxic metals, solvents, or fillers slip through in low-grade batches. That goes beyond spoiled experiments—it can create risk for patients or workers. There are famous cases where impurities caused medication shortages, ruined research, or even led to lawsuits. It’s not just a technical issue: it's a public health concern.

Controlling contaminants keeps everyone safe. The World Health Organization flags ingredient purity as a top safeguard against counterfeit drugs and dangerous additives. In my own experience sourcing ingredients for a nutrition program, purity wasn’t just paperwork: it was about the trust our clients placed in our product. That meant paying more for clear origin, better batch testing, and reliable supply partners.

How to Get the Grade You Need

A few practical moves can save big headaches. Ask for certificates of analysis, and read them—don't file them away unread. Check the standards met: USP for pharmaceuticals, FCC or E-number for food. Push suppliers to answer questions. Reliable partners flag substitutions or upgrades, they don’t bury the details in fine print. That way, you catch a problem before it spirals into a disaster.

Regulatory bodies like the FDA suggest picking suppliers prepared to be transparent. Organizations should establish written standards—what’s the lowest acceptable grade? If you need to switch suppliers or grades, run trial batches and compare results. Small upfront costs catch problems that would otherwise show up late, when a batch fails or recalls threaten the bottom line.

Looking Ahead

Demand for clear, honest labels and traceable purity keeps rising. New testing methods let buyers be pickier, and real-time transparency builds consumer trust. If you work with products where purity makes a difference, paying close attention always brings greater returns than cutting corners. Good decisions up front keep doors open—and teams out of trouble.

Understanding What Your Compound Needs

Before opening a new bottle from the supplier, I glance at the label. It lists peculiar warnings, storage temperatures, symbols, sometimes what not to mix. This practice—taking a few seconds to absorb storage advice—protects my safety and project outcomes. Over the years, knowing just the basics about chemical storage has saved several labs from headaches, fire marshals, and ruined research.

Temperature Matters More Than You Think

Some compounds break down fast if left on a warm benchtop. Many—especially organics or biologicals—need cool, dark storage to avoid decomposition or the build-up of dangerous gases. For example, many pharmaceuticals lose potency in the sun. Research from the US National Library of Medicine shows that warmer conditions can cut a drug’s shelf life by half or more. A fridge running between 2°C to 8°C works for a good number of delicate substances, but not all. There are compounds that freeze and change form or lose crystal structure below a certain temperature, so don’t dump everything with your lunch. Simple digital thermometers or data loggers keep the guesswork out.

Moisture Ruins More Than Paperwork

I’ve seen white powders turn useless after one rainy week in a drawer. Water vapor sneaks through thin caps and weak seals, especially with hygroscopic materials. Some reagents, like sodium hydroxide or silica gel, attract water out of thin air and clump together. Desiccators filled with fresh drying agents give a solid first defense. More stubborn samples get sealed in glass ampoules or stored with inert gas, a method not just for chemical snobs; even high school labs use it for air-sensitive powders. A tight cap after every use makes all the difference.

Sunlight Wrecks What You Can't See

Many common chemicals degrade when sunlight passes through a blazer of a window. Some, like silver nitrate or certain peroxides, will turn color or lose punch after a day in the light. Inexperienced folks stick everything on shelves “for easy access” and soon find brown bottles are brown for a reason: they’re made to block UV rays. Shaded storage, opaque bins, or even a cardboard box does a world of good where special cabinets aren’t possible.

Label Everything—No Shortcuts

Forgotten vials can put people in harm’s way. Every tube should have the name, concentration, and open date right on the label. Think of it as your future self’s lifeline. I once cleaned out an old university fridge packed with mystery jars—most, unlabeled. Dangerous wastes build up when folks “just stick it somewhere.” A clear label and chemical inventory cut mistakes, disposal costs, and accidents. It keeps your group’s work transparent, which strengthens trust and safety for everyone, including new team members.

Segregation: Better Safe Than Sorry

Some substances invite disaster if stored together. Acids next to bases, organics near oxidizers, or solvents with strong acids have burned more than one researcher. The National Institutes of Health supports using color-coded shelves or separate cabinets for different classes. Avoiding even a small spill or interaction can avert emergencies. It’s no secret that proper separation saves lives—and inspections fly by when storage passes muster.

Staying Proactive Brings Real Value

Learning storage guidelines is not just rule-following. It’s every researcher’s responsibility, and the benefits run deep. Good storage protects health, preserves investment, and upholds the integrity of scientific work. Investing energy up front pays off in less waste, fewer incidents, and more reliable results. It’s the simple habits, repeated daily, that dodge big disasters and keep progress moving forward.

What Is 1-Vinyl-3-Butylimidazolium Trifluoromethanesulfonate?

People in chemistry labs and research settings keep running into chemicals with long, hard-to-pronounce names. 1-Vinyl-3-butylimidazolium trifluoromethanesulfonate falls into that camp. It belongs to the “ionic liquids” family. Chemists get excited about this group because these liquids can dissolve a lot of things, stay stable at high temperatures, and don't evaporate like water or alcohol. Industrial labs value them for battery work, organic synthesis, and all sorts of clean-energy projects.

Looking at Health and Safety

Once a chemical like this starts showing up in more labs, people start asking about its safety. Safety Data Sheets call for wearing gloves, goggles, and a lab coat. Anyone who’s spent time handling ionic liquids knows: just because a liquid doesn’t smell or splash like acid doesn’t mean it isn’t tricky. Some ionic liquids hardly sting the nose, yet still hurt skin or lungs.

The scientific world doesn’t have much toxicity data on this particular compound. Most toxicology databases only have information for a handful of ionic liquids. The story is often the same: researchers are still collecting evidence. What we do know, based on its structure, points to some basic risks. Trifluoromethanesulfonate groups contain fluorine, and that brings hazards if they break apart, especially under high heat or in a fire. Imidazolium-based liquids sound gentle, but some cause genetic changes in cells; some even build up in the environment, which could harm aquatic life.

The Worker’s Perspective

People working with chemicals every day pick up healthy respect for unknowns. A few drops on the skin can cause redness or burning. Breathing in dust or fumes around these compounds sometimes leads to coughing or headaches. I remember seeing a colleague get a rash after a minor spill of a different ionic liquid — it left us all more cautious.

Environmental Impact

Disposing of ionic liquids needs care. Sewer systems or regular trash bins don’t cut it. When not handled properly, imidazolium-based liquids trickle into water supplies, affecting fish and microorganisms. Unlike table salt or vinegar, these chemicals don’t break down easily; they hang around in soils or streams for months or longer.

Legislation hasn’t caught up with every new ionic liquid yet. Manufacturers must label shipment containers for skin, eye, and respiratory hazards, but those warning symbols don’t always tell the whole story. Academic journals published some worrying reports about long-lasting effects in aquatic environments. That alone should make anyone double-check their waste disposal plans.

Moving Toward Safer Use

Teaching and training help. Old hands in chemical storage rooms pass on lessons about double-gloving and using chemical fume hoods, even for compounds that seem less aggressive. Labs invest in better spill kits. Some universities now add stricter labeling rules, forcing researchers to spell out risks for every bottle, no matter how exotic.

Research keeps plugging away, writing up new studies. Scientists compare cancer, irritation, and environmental effects across different ionic liquids. They look for better, safer alternatives and invent safer versions through chemical tweaks. Until this library of data fills out, the best bet stays with respect for the unknown, smart personal protection, and thinking twice before disposal. New chemicals aren’t just cool science — they need thoughtful, careful handling every step of the way.

What Shelf Life Really Means

People often ignore expiration dates printed on products, treating them as a suggestion rather than a limit. I’ve done it with everything from canned beans to sunscreen. The truth is, shelf life goes beyond marketing—it’s the line between safety and risk. In food, that date matters because nutrients break down over time, flavors change, and, more importantly, bacteria can find their way in. Pick up a loaf of bread; after a week it gets moldy, turning what seemed like a harmless staple into a health hazard.

Health and Safety at the Grocery Store

I’ve seen shoppers hunt for milk at the back of the fridge hoping to grab the freshest jug. That’s not paranoia—it’s practical. Milk with an expired date can spoil, even if it looks fine for a day or two. In the case of fresh produce, the shelf life might not have a printed date, but the color, texture, and smell usually tell the story. Following expiration dates isn’t just about avoiding bad taste; it’s about reducing the chance of foodborne illness. According to the CDC, millions in the U.S. get sick from contaminated food every year, pointing to the need for attention beyond just appearance.

Packaged Goods Aren’t Immune

Snacks, cereals, or canned vegetables seem long-lasting, but even those come with expiration dates for a reason. I once opened an old box of crackers left in the pantry, thinking dry food couldn’t go bad. Stale and tasteless, those crackers also showed signs of insect activity—something nobody wants to see. The additives that protect flavor wear down over time. Vitamins lose their strength, and preservatives eventually give up the fight against spoilage, all of which take a toll on quality and health.

Household and Health Products: Not Forever

Medications and cosmetics land in a different category but follow the same logic. A bottle of painkillers in my medicine cabinet expired last year. Although tempting to take, those pills may not work as advertised, and in some cases, they could do harm. Creams, sunscreens, or toothpaste can lose their effectiveness or even grow bacteria after their recommended timeframe. The FDA has warned that expired medicine can either be useless or, worse, toxic. That’s not a risk anyone should gamble with.

Moving Toward Smarter Choices

Throwing out unused food or expired items feels wasteful, but it protects the household from unnecessary risk. Simple habits help—rotate pantry stocks, buy smaller packages for products used infrequently, and always check the date before purchasing. Local food drives or apps that match shoppers to discounted near-expiry products can keep edible food out of the trash and help stretch tight budgets. Making these small changes stops the cycle of waste without sacrificing health.

Understanding the Labels for Better Living

Reading “best by,” “use by,” or “expires on” labels is about protecting yourself and your family. The cost of ignoring those dates—food poisoning, infections, or wasted money—is too high. It’s worth taking a moment during each shopping trip or before tossing something in the pan to read that tiny stamp. Those numbers do more than fill up a label; they give clear direction for safe, smart living.