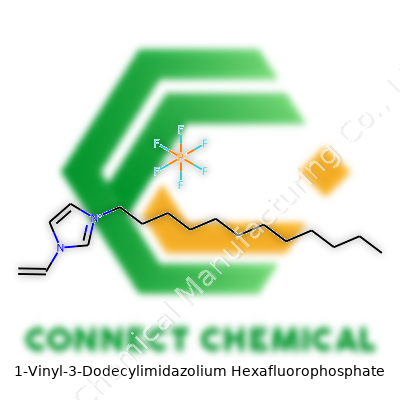

1-Vinyl-3-Dodecylimidazolium Hexafluorophosphate: A Practical Perspective

Historical Development

Researchers have long looked for unconventional solvents and functional materials that could outpace traditional organic compounds in safety and adaptability. Around the late 1990s and early 2000s, curiosity about imidazolium-based ionic liquids solidified their place in labs focused on green chemistry. By introducing bulky cations such as 1-vinyl-3-dodecylimidazolium and pairing them with hydrophobic anions like hexafluorophosphate, chemists tapped into low-volatility, non-flammable alternatives for a host of applications. Publications from research institutes in Germany, China, and the United States began to highlight how these substances could act as both solvents and building blocks for advanced functional materials. The gradual shift toward sustainability and minimizing hazardous waste propped up the reputation of these ionic liquids in fields ranging from electrochemistry to polymer engineering.

Product Overview

1-Vinyl-3-dodecylimidazolium hexafluorophosphate, widely discussed as [C12VIm][PF6] in publications, belongs to a group known for breaking traditional boundaries in performance and environmental compatibility. The addition of the vinyl group sets it apart, allowing the compound to participate in polymerization and enable hybrid material synthesis. Its structure gives it a robust hydrophobic character from the dodecyl chain, paired with the vinyl’s ability to facilitate unique modifications. This dual nature brings practical versatility in making functional surfaces, separation membranes, advanced electrolytes, and more, responding directly to increasing technical demands across multiple sectors.

Physical & Chemical Properties

In handling [C12VIm][PF6], the senses catch its faint yellow tint and oily consistency at room temperature, which hints at its long alkyl side chain. The compound tends to form viscous liquids under moderate humidity but may crystallize in low-moisture storage. Its melting point sits between 50°C and 60°C, which allows for easy manipulation without harsh thermal conditions. Most ionic liquids tout elevated electrochemical and thermal stability, and this holds true here. High decomposition temperatures (roughly 350°C) and strong resistance to oxidation stand out among its peers. The substance remains insoluble in water but interacts freely with many organic solvents, adding to its functional range.

Technical Specifications & Labeling

Manufacturers supply [C12VIm][PF6] as purified liquid or crystalline solid, often with a purity exceeding 98%. The label lists molecular weight (472.42 g/mol), color, and CAS number for traceability in quality control and regulatory filings. Standard care includes storage in airtight, light-protected containers, away from moisture and reactive chemicals such as strong acids or bases. Laboratory vials typically feature tamper-evident caps and barcoded traceability to support compliance and consistency, especially in regulated industries or academic R&D.

Preparation Method

The lab route for [C12VIm][PF6] follows a two-step synthesis common to many ionic liquids, but small details make a real difference in yield and purity. First, chemists quaternize 1-vinylimidazole with 1-bromododecane, yielding 1-vinyl-3-dodecylimidazolium bromide as the intermediate. Slow reaction rates often require heating under inert conditions and prolonged stirring, which can mean days in the lab, not hours. Purification through repeated washing with nonpolar solvents ensures removal of residual bromides and by-products. In the second step, anion exchange with potassium hexafluorophosphate converts the bromide salt to the desired hexafluorophosphate. Careful washing and drying—sometimes under reduced pressure—remove any residual potassium or water, both of which disrupt product performance in electrochemical or separation tools.

Chemical Reactions & Modifications

One critical advantage of the vinyl group is its reactivity. Using established radical or cationic polymerization, this ionic liquid turns into robust poly(ionic liquid) membranes, useful in creating selective barriers. By modifying the imidazolium ring or the alkyl side chain, researchers have generated whole families of derivatives, each meeting precise technical demands: tweaking hydrophobicity, tuning melting point, and shifting electrochemical windows. These reactions often shape new materials for batteries, sensors, and catalysts, cutting down reliance on volatile organic compounds or rare metals.

Synonyms & Product Names

Science literature frequently refers to this molecule as 1-vinyl-3-dodecylimidazolium hexafluorophosphate or, simply, [C12VIm][PF6]. Other catalog listings may show variations such as “N-vinyl-N-dodecylimidazolium hexafluorophosphate” or “VImC12PF6.” The naming conventions largely depend on publication standards or chemical supplier catalogs, with occasional confusion due to variations in dodecyl or imidazolium spelling. Cross-referencing CAS registry numbers can cut through this ambiguity—making sure chemists, buyers, and regulatory staff talk about the same substance.

Safety & Operational Standards

Hands-on safety matters. Ionic liquids usually claim “non-flammable” and “low volatility,” both true of [C12VIm][PF6], but careless lab practice can mean exposure to hydrolysis products or unintentional contact with strong acids releasing HF, a hazardous gas. Handling in a well-ventilated fume hood, with nitrile gloves and splash-proof goggles, cuts down direct skin or inhalation risks. Accidental contact with skin brings irritation, while eye splashes demand immediate flushing and medical observation. For spill events, absorbent pads and washing with lots of water stand as routine measures. Long-term storage in original containers, away from light, helps avoid degradation—important not only for shelf life but also to maintain known toxicity profiles.

Application Area

Electrochemistry labs count on [C12VIm][PF6] for its role as an electrolyte and separator membrane component in supercapacitors, lithium batteries, and fuel cells. The polymerizable vinyl function lets factories produce membrane materials with precise ion selectivity, giving a performance edge in separating gases, liquids, or ions for industrial and environmental technology. By keeping non-volatility and hydrophobicity, industrial processes like organic synthesis, catalysis, and extraction replace harmful solvents, moving toward eco-friendly protocols. Academia relies on its amphiphilic structure to probe new forms of materials—photonic devices, antimicrobial coatings, or molecular recognition sensors—pushing experimental setups far beyond legacy alternatives.

Research & Development

The innovation pipeline for [C12VIm][PF6] looks busy. Recent research maps out better routes to lower residual impurities and scale up the anion exchange for cheaper, cleaner output aimed at industry. Nano-engineers experiment with hybridization, embedding the ionic liquid in mesoporous scaffolds or blending with metal-organic frameworks for fresh catalytic behavior. Journals highlight findings in increasing ionic conductivity and reducing permeability to water or air, attempting to punch through performance walls that have blocked progress in batteries or separation technology. Ongoing collaborations with environmental toxicologists and regulatory bodies steer the compound’s development, directly confronting not only technical but also ethical challenges about long-term safety.

Toxicity Research

Safety data for [C12VIm][PF6] keep growing, recognizing that all ionic liquids—despite “green” branding—can pose ecological and health risks. Chronic exposure may harm aquatic life, as the compound resists easy degradation in the environment, tending to bioaccumulate in water systems. In the event of worksite mishandling, acute exposure brings skin and mucous membrane irritation; rare but severe reactions link back to the hexafluorophosphate anion’s ability to react with acids. Animal models and in vitro toxicity studies call for responsible use and tighter containment or waste treatment protocols, directly pushing policy and corporate best practices. Waste minimization and closed-loop recycling offer paths for industry to maintain both effectiveness and environmental stewardship.

Future Prospects

[C12VIm][PF6] stands at a crossroads between convenient lab reagent and future industrial staple. Demand keeps pulling it into large-scale battery manufacturing and new chemical separations. Growth in electric vehicles, renewable energy storage, and advanced materials research promises a solid stretch of rising use. Yet, the field wrestles openly with toxicity and end-of-life disposal, spurring more rigorous research into alternative anions or complete circular recycling routines. Collaboration among manufacturers, regulators, and scientists holds the key to balancing performance with responsibility, shifting ionic liquids from niche options into mainstream, sustainable solutions in chemistry and engineering.

Untangling a Unique Molecule

Chemists can spot an unusual cation and a robust anion in this salt. The core piece starts with imidazolium, a five-membered ring featuring two nitrogen atoms. The “1-vinyl” side extends the molecule’s reactivity, with a vinyl group (–CH=CH2) at the first position on that ring. Right there, polymer chemists lean in close; vinyl groups grab attention for their role in polymerization and reaction tuning.

Then comes the dodecyl chain. Dodecyl means twelve carbons in a straight line. Long alkyl chains like this deliver oil-loving (hydrophobic) behaviour. The third position on the imidazolium ring ties to that dodecyl group, anchoring it tightly. Anyone who’s run an extraction or tried to separate phases in the lab knows what a dramatic shift a long chain like this can make. Suddenly, the ionic liquid doesn’t just dissolve in water—it starts playing with organic phases, altering solubility for both hydrophilic and hydrophobic molecules.

The Other Half: Hexafluorophosphate

Chemists often see PF6– (hexafluorophosphate) paired with imidazolium cations. PF6– brings stability and low reactivity. Unlike chloride or nitrate, PF6– rarely competes in reactions, so the main action happens on the cation side. This makes it easier to use the salt in synthesis without too many surprises along the way.

From a practical point of view, salts like this often melt below 100°C, falling into the “ionic liquid” category. Workers handling synthesis or electrochemistry appreciate that property since these materials flow like oils yet conduct electricity—mixing the best of both worlds from molten salts and solvents.

Why Chemists Care

I remember setting up extraction columns in grad school. Half the time, regular solvents tangled into complicated waste headaches. Tossing in an ionic liquid with a dodecyl chain suddenly gave me sharper separations. The hydrophobic tail in the molecule coaxed certain products out of an aqueous layer, almost like it remembered its own friends from organic chemistry.

But it’s not just about moving molecules from one layer to another. The vinyl group opens up avenues for polymer chemists to create materials with built-in ionic conductivity or tough, flexible backbones. Batteries, sensors, even catalyst supports—all can benefit from a tweak to the cation or anion in these salts.

Room for Caution—and Progress

PF6– anion choices historically raised environmental questions. Hexafluorophosphate resists breakdown, which means disposal deserves real thought. Labs need to handle waste properly to avoid long-term soil and water impacts. Moving toward safer anions or recycling schemes could help reduce the downsides while keeping the performance benefits.

Success stories around ionic liquids often hinge on balancing tunable chemistry with responsible lab practice. 1-Vinyl-3-dodecylimidazolium hexafluorophosphate is a striking example of how structure shapes function, reaching beyond the bench into safer, smarter ways to build new materials in chemistry. Every slight tweak to the imidazolium ring or the counterion can transform performance, leading to progress that doesn’t come at the environment’s expense.

What Sets This Compound Apart

People who spend any amount of time in a chemistry lab or in materials research start noticing a few repeat players, and ionic liquids are tough to overlook. One standout is 1-vinyl-3-dodecylimidazolium hexafluorophosphate, a mouthful of a name, but a workhorse in advanced material science. Its unique blend of thermal stability, low volatility, and electrochemical properties makes it more than just another bottle on a shelf.

Electrolytes for Supercapacitors and Batteries

As the world keeps searching for cleaner energy and longer-lasting devices, the structure of this ionic liquid makes it a natural fit for energy storage. Cutting-edge supercapacitors need electrolytes that handle high voltages without breaking down. This liquid answers that call with solid conductivity and a wide electrochemical window. Most common lithium-ion batteries suffer from flammable solvents and aging issues. Researchers add this ionic liquid into electrolytes to reduce risks of fire and to extend device lifespans. There's hard data showing that cells using it can sustain more cycles because the liquid resists decomposition under stress.

Catalysis and Green Chemistry

Green chemistry in the lab moves forward when people use less toxic solvents. Old-school organic solvents smell awful, pollute, and sometimes send lab staff to the nurse’s office. This ionic liquid acts as an alternative medium for many reactions. In practice, chemists have used it to clean up Suzuki-Miyaura cross-coupling and Heck reactions, giving higher yields with fewer byproducts. The liquid dissolves a range of organic and inorganic compounds and comes out of reactions unchanged, so you can recover and reuse it. That saves money, reduces chemical waste, and protects people running the experiment.

Nanomaterials and Polymer Science

The push toward lighter, smarter materials in tech and healthcare wouldn’t get far without just the right monomer. The vinyl group on this ionic liquid makes it a starting point for synthesizing advanced polymers. Polymers built from this monomer exhibit unique conductivity and flexibility, which opens the door for wearable electronics and soft robotics. The long dodecyl chain brings key self-assembly features, helping produce well-defined nanostructures. For those who have struggled with inconsistent nanoparticle sizes, this liquid offers a solution by stabilizing them during synthesis, thanks to strong ion-pair interactions.

Corrosion Protection and Antistatic Coatings

Nobody likes seeing equipment fail because of rust or static shocks. Industries facing these headaches turn to coatings built from functional ionic liquids. This compound’s hydrophobic dodecyl tail helps form robust, water-resistant films on metal surfaces. Tests show these coatings shield against corrosion and prevent build-up of static charge. In the electronics world, these features matter for keeping sensitive components safe and reliable.

What Could Make These Applications Go Further

Despite all its promise, price sometimes slows adoption. Sourcing specialty chemicals for large-scale manufacturing can add up fast. There’s a need for more sustainable production routes and wider distribution networks. Patents and regulatory barriers also create hurdles. Cross-collaboration between academic labs and industry could help bridge that gap, spreading real-world experience and best practices. If processes for recycling and repurposing these ionic liquids develop further, both the environment and bottom lines will benefit.

What Makes This Compound Worth Talking About?

Some chemicals pass through the lab almost unnoticed, but 1-vinyl-3-dodecylimidazolium hexafluorophosphate sends up a few red flags. From my own bench work, any ionic liquid, especially one with a long alkyl side chain and a tough-sounding anion like hexafluorophosphate, demands respect. The compound brings innovation to materials science, acting as a promising ionic liquid for energy storage, catalysis, and advanced coatings. That sort of versatility can tempt folks to think a bottle on the back shelf will take care of itself. It won’t.

Risks At Eye Level

I’ve seen what happens when labs downplay the hazards of these imidazolium compounds. Spill one on a bench, and the task turns sticky—literally and figuratively. The hexafluorophosphate anion signals danger, as its decomposition releases toxic hydrogen fluoride gas. The vinyl group means easy polymerization under the wrong conditions. Skin contact sometimes brings delayed reactions; it burns or irritates hours after the splash.

Temperature, Light, and Air—The Critical Trifecta

Ask any synthetic chemist about ionic liquids; temperature control tops the playlist. 1-vinyl-3-dodecylimidazolium hexafluorophosphate holds up best far from sunny window ledges or hot sample stirrers. I keep bottles below 25°C in a temperature-controlled spot. UV light attacks the vinyl group, souring the entire flask over a few afternoons on an open shelf.

The air around us brings water and dust. Both have no business near this compound. From experience, a loose cap means performance drops and risks climb. Moisture interacts with the hexafluorophosphate, increasing the formation of corrosive products. Glass bottles with tight PTFE-lined screw caps stay dry and clean. For longer storage, adding a desiccant pouch in a secondary sealed container keeps things crisp.

Segregation, Labeling, and Accountability

Colleagues used to ask why I fussed about bottle labels and shelf placement. Mistaken swaps between similar-looking bottles caused chaos. A clear, durable label on both the bottle and the storage box spells out the chemical, the date received, and the risk phrases. Flammable and reactive chemicals should stand on dedicated shelves, away from acids and bases.

Every chemist picking up a bottle ought to see a quick reference—the location and date ensure fresh material, and unnecessary surprises get cut down. In my practice, any mystery vial goes straight to waste unless you can prove its identity. Accountability starts with the person storing it. Too many stories in campus labs end in regret because someone stashed a risky sample behind more benign-looking bottles.

Raising The Bar—A Culture of Vigilance

OSHA’s chemical hygiene rules set a floor, but personal discipline builds a stronger ceiling. Safety audits treat this as a touchstone: Track each movement, log the location, and make sure every person handling the material knows the risks. Digital inventory tools help, but they only work if someone checks them often. Spot checks sharpen instincts and catch sloppiness early.

Some labs rotate the chemical supply every six months. Expired chemicals get neutralized and disposed of, never shoved behind fresher stock. Training new team members, not just with a folder, but with real tours of good and bad examples, seems to stick with people. The more eyes on the system, the fewer accidents down the line.

Toward Smarter, Safer Labs

Taking shortcuts with 1-vinyl-3-dodecylimidazolium hexafluorophosphate doesn’t just risk wasted research—it risks health and liability. Staying smart with dry air, cool temperatures, no direct light, and frequent checks stops small problems from becoming big ones. Better habits, at the shelf and at the bench, build trust, protect work, and let science move forward.

Living With Mystery Chemicals

Feeling wary about a mouthful like 1-vinyl-3-dodecylimidazolium hexafluorophosphate doesn’t take a chemistry degree. Like a lot of new or not-so-well-known chemicals, background info can seem either buried in journals or weighed down by jargon. This compound belongs to a broader family of ionic liquids, often designed to make industrial processes run smoother or greener. But anyone who has ever tried to scrub engine grease off their hands knows that “industrial” doesn’t automatically mean “safe.”

What Do We Really Know?

Experts keep ionic liquids under close watch because some can be less volatile and less flammable than old-school solvents. That sounds good for workplace fire risks and air quality, and it matters—a 2020 study from the journal Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety lays out how these compounds often stay put rather than evaporate. It’s easy to get excited by the label “green solvent,” which shows up on grant applications and, unfortunately, sometimes on chemical flyers too.

When it comes to toxicity, not every ionic liquid acts the same. The cation in this one, based on an imidazolium ring, has been flagged in multiple reports for being more toxic than more familiar salts used in chemistry labs. The side chain—here, dodecyl—makes it more likely to stick to fats and cell membranes. Animal studies and limited cell-line work suggest that long alkyl chains can damage aquatic life in low concentrations. As for the anion, hexafluorophosphate, if it breaks down (especially under acidic or hot conditions), you get hydrofluoric acid—a substance even seasoned chemists dread for its pain and tissue damage. The chemical safety data sheets (SDS) from suppliers echo this: gloves, goggles, and sometimes even a fume hood.

Why Should We Care?

Most people won’t ever walk past a jug of this stuff at home, but lab workers and researchers do. They trust protocols, but those rules build on toxicology that’s sometimes patchy or outdated. Environmental regulators have only recently started considering the fate of ionic liquids, and the research does not yet cover long-term buildup in soil or water. A European Chemicals Agency review warned that chronic exposure may cause issues for fish and invertebrates, highlighting real stakes for rivers downstream of manufacturing sites.

A chemical like this isn’t just a number on a label—its story unfolds over years and through the people handling it. In one university lab, a friend watched his project on ionic liquids get held up after a spill, not because of fumes, but because the safety crew needed hazmat gear and a specialized disposal plan. That’s not what you’d expect from something billed “eco-friendly.”

Best Practices and Push for Transparency

Working with unknowns means putting health and honesty ahead of convenience. Researchers have called for more complete testing, including how these chemicals behave after they leave the lab. Regulators should prioritize funding for long-term assessments, since right now even peer-reviewed records skip a lot of real-life scenarios.

Anyone using compounds like 1-vinyl-3-dodecylimidazolium hexafluorophosphate should take every label warning seriously, even if the marketing claims sound reassuring. Safety data sheets, peer-reviewed toxicology studies, and clear labeling make a difference. Demand for transparency from chemical producers helps researchers, environmental watchdogs, and the people on the front lines, who deserve more than a shrug and a promise that “it’s probably fine.”

Insights into the Compound’s Quality

If you’ve ever walked through a chemistry lab or scrolled through a fine chemicals catalog, you pick up pretty quickly that the success of an experiment can hang on the purity of your chemicals. For a specialized ionic liquid like 1-Vinyl-3-Dodecylimidazolium Hexafluorophosphate, purity carries real weight. Confidence in purity often spells the difference between a well-behaved reaction and a trail of confusing side products. For researchers and professionals, laboratories lean toward samples that reach 98% purity or higher. Some suppliers label their product as “high purity” and back it up with actual analytical reports. In my own years in material science, most user groups seek out confirmation documents: NMR, HPLC, or elemental analysis certificates accompanying the stock bottle always earn a nod of approval.

Industrial scale processes, especially those in electronics manufacturing or catalysis, focus precisely on these specifications. Metals or halide contamination creeps into sensitive syntheses, so trustworthy suppliers test down to the ppm level. Users shouldn’t have to wonder if a batch will introduce unidentified contaminants, or if they’ll get performance swings from bottle to bottle. More than once, I’ve seen projects delayed by an impurity that forced a late-stage protocol change or a switch to a new vendor.

Packaging Size: Beyond Tiny Samples

On the packaging front, practicality rules. Researchers working up an initial test might only need a 1-gram vial, but anyone pushing toward pilot batches quickly jumps to 10 or 25 grams, sometimes larger. From my own orders, the smallest glass vials give flexibility for lab-scale screening, while plastic wide-mouth jars make sense for those scaling up. More recent shifts in procurement trends show that researchers expect several options out of the gate—nobody wants to cut open a kilo bottle to weigh two grams for screening.

Suppliers also recognize some projects demand much larger volumes. Bulk orders occasionally stretch to the level of 100-gram packs, or even up to kilograms for industry trials or continuous reactions. It’s refreshing to see vendors listen to feedback and offer improved closures like PTFE liners, limiting the risk of chemical degradation or leakage. Built-in tamper-evidence and traceability labels also earn trust, not just for quality assurance, but for the ability to audit a project if anything goes sideways.

The Push for Transparency in Supply Chains

Transparency matters. Scientists and engineers shouldn’t have to guess if their supply is up to par or scramble to decipher a vague data sheet. In my experience, the companies earning long-term customers are the ones who are up front about both purity and available sizes—and who publish actual test results, not just broad marketing claims.

Consider the stakes: pharmaceutical development, advanced batteries, research into ionic liquids—progress in each field hinges on consistency and clarity about what's in each bottle. Shortcuts or hidden variability raise big problems and can waste entire research cycles or threaten process safety. Errors arising from unflagged impurity or incorrect handling feed into expensive troubleshooting sprints, not discovery or innovation.

Promoting Safe and Responsible Usage

As someone who has spent late nights with both breakdowns and breakthroughs in the lab, I vouch strongly for detail-oriented suppliers emphasizing clear documentation, actual purity metrics and honest packaging size options. Reliable sourcing isn’t just a box to check—it protects investments, encourages collaboration and drives progress. More open sourcing, third-party verification and post-purchase feedback channels would push everyone closer to safer, more successful workflows. Honest, well-documented supply chains don’t just benefit the lab—they ripple through the broader research community.