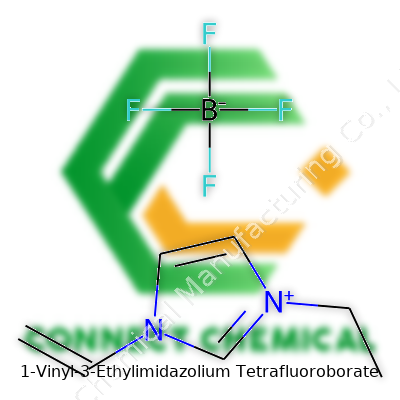

1-Vinyl-3-Ethylimidazolium Tetrafluoroborate: Insight Across Production, Use, and Research

Historical Perspective

Chemists have been working with ionic liquids for decades, but the story of 1-vinyl-3-ethylimidazolium tetrafluoroborate tracks back to laboratory efforts of the late 20th century. Many were after stable, non-volatile solvents that could stand up to traditional organic solutions. The journey began in earnest once researchers realized that tweaking the imidazolium ring changes properties in dramatic ways. The vinyl and ethyl side chains made this compound a gateway to polymer chemistry and green solvents. By the early 2000s, technical journals highlighted both easier synthesis routes and cleaner properties than volatile organic compounds. For researchers invested in process intensification, this ionic liquid felt like a missing puzzle piece.

Product Overview

Product catalogs list 1-vinyl-3-ethylimidazolium tetrafluoroborate as a clear to pale yellow liquid, typically intended for laboratory or pilot-scale use. The inclusion of the tetrafluoroborate anion offers low viscosity and strong ionic conductivity, which set it apart from chloride or hexafluorophosphate alternatives. With its vinyl group, this compound isn’t just a solvent; it acts as a monomer in polymerization and copolymerization reactions. The trade names in circulation reflect various degrees of purity, and suppliers usually specify content above 98%, appropriate water content, and low halide contamination. Many industrial users rely on these standards to ensure repeatability and process safety, as minute impurities often throw synthetic plans out the window.

Physical and Chemical Properties

This ionic liquid doesn’t evaporate under ordinary lab conditions. Boiling points exceed the working range of most glassware, and its thermal stability up to 250°C gives it an edge during elevated-temperature syntheses. The density at room temperature falls near 1.2 g/cm³, and it mixes smoothly with polar solvents. It shows a clear UV absorption profile, providing an easy handle for chromatographic monitoring. The conductivity is notable, allowing more efficient electrochemical processes. You get a slightly sweet, almost ether-like smell, but it never stings the nose like chlorinated solvents. One issue that can’t be ignored is hydrolysis in moist air, which eats away at BF4⁻ to slowly generate HF and trigger side reactions.

Technical Specifications and Labeling

A bottle on the shelf generally displays several key details: the CAS number, batch number, manufacture and expiry dates, and purity percentage. Most suppliers run Karl Fischer titration to guarantee minimal water presence, since water can trip up many planned reactions. Labels warn against inhalation and moisture exposure, and often include QR codes for digital access to safety and compliance data. Regulatory status varies, but in many countries, tracking and traceability standards now apply to imidazolium-based ionic liquids because of their expanding use in chemical manufacturing.

Preparation Method

In most laboratories, preparation starts by reacting 1-vinylimidazole with ethyl bromide or ethyl chloride in a polar aprotic medium under inert atmosphere. The reaction kicks off at room temperature, and once the imidazolium bromide or chloride salt forms, metathesis with sodium tetrafluoroborate swaps the halide for BF4⁻. The mixture then goes through solvent washes, filtration, rotary evaporation, and vacuum drying to remove unreacted starting materials and hydrolysis byproducts. Thoughtful handling during metathesis and product isolation avoids unwanted hydrolysis and boosts yield. Some pilot-scale manufacturers adapt this approach, scaling up with continuous flow reactors and inline monitoring to better manage temperature and moisture.

Chemical Reactions and Modifications

The vinyl group on this molecule flips on broad reactivity, unlocking free radical polymerization and crosslinking with substrates ranging from acrylates to styrenics. In my own work, running vinylimidazolium-based polymerizations cut down the use of toxic initiators and eliminated volatile solvents from the process. It copolymerizes well with anionic and zwitterionic monomers, supporting innovations in membranes and electrolyte systems. The presence of BF4⁻ as a non-coordinating anion helps minimize side reactions in metal complexation or catalysis, and chemical modification of the imidazolium backbone expands the palette of function even further, driving research into custom ionic liquids for specific catalysis and separation tasks.

Synonyms and Product Names

Beyond its formal name, you’ll find the compound listed as [VEIM][BF4], 1-vinyl-3-ethylimidazolium tetrafluoroborate, and sometimes as 1-vinyl-3-ethylimidazolium boron tetrafluoride. Commercial vendors and researchers alike toggle between these denotations, but standardized IUPAC and CAS labeling tend to dominate regulatory paperwork. Avoiding ambiguity matters — a simple mislabeling slows down audits, risks compliance, and muddles research communications.

Safety and Operational Standards

Handling ionic liquids brings its own requirements. While volatility stays low, hydrolytic instability of the BF4⁻ anion produces hydrogen fluoride in the presence of water, posing a risk to exposed surfaces and lab workers. Gloves rated for chemical protection plus polycarbonate goggles make up the standard kit. Clean, dry atmosphere in storage — often a desiccator or nitrogen-purged glove box — guards against moisture ingress. SDS documents outline that accidental skin or eye contact demands immediate washing, while inhalation calls for open air and medical attention. Regulatory shifts now emphasize HF detection strips and active fume extraction wherever scale exceeds bench quantities. Waste management programs demand neutralization before disposal, not just for environmental compliance but also to keep pipes and glassware clear of corrosive residues that build up quickly without proper protocol.

Application Area

Across my own projects and in published research, applications cluster around solvent extraction, electrochemical devices, and the rising field of “smart” functional polymers. Its role in electrodeposition and battery electrolyte development grows each year. Colleagues in government labs tap this ionic liquid for CO₂ capture at moderate temperatures, while research partners at universities employ it as a polymerizable ionic liquid for ion-exchange membranes in water treatment and fuel cell projects. Few solvents deliver the same combination of non-flammability, tunable polarity, and polymerizability.

Research and Development

Current R&D pursues new synthesis routes to lower cost and limit byproducts, scaling up reliable productions to meet commercial needs. Some teams experiment with swapping out BF4⁻ for greener anions, searching for a blend of low toxicity and improved recyclability. Research groups document that this ionic liquid helps dissolve cellulose, creating opportunities for bio-based polymer production. Analytical chemists constantly scan for impurities and breakdown products, working to extend usable lifetimes and push operational envelopes further. My own experience shows that detailed reaction monitoring bridges gaps between pilot trials and large-scale implementation. Journals now fill up with comparative studies on conductivity, viscosity, and performance, reflecting a growing consensus: data-driven design drives adoption.

Toxicity Research

Several studies probe toxicity in aquatic life forms and mammalian cells, noting that imidazolium species in general display moderate toxicity if mishandled. Tetrafluoroborate-based ionic liquids fare better on volatility measures, but there’s evidence hydrolysis products like HF raise environmental red flags. Long-term exposure data remains scarce; most evidence comes from controlled lab settings. Wherever ionic liquids meet the water table or biological systems, proper containment and remediation becomes non-negotiable. Ongoing research leans into eco-toxicology and biodegradation, in hope that newer formulations will carry more favorable environmental footprints.

Future Prospects

With the global push for greener and safer chemicals, 1-vinyl-3-ethylimidazolium tetrafluoroborate sits at the crux of modern material science and cleaner process design. The market landscapes indicate growing investments from battery manufacturers, advanced polymer makers, and clean-tech startups. Teams are experimenting with derivatives that absorb and sequester greenhouse gases, or serve as catalyst support in sustainable transformations. Advances in synthetic efficiency, purification, and waste treatment drive adoption. Continued partnerships between academia and industry generate innovations and best practices, promising safer materials, smarter regulatory oversight, and genuine step-changes in what solvents and functional monomers can deliver.

Behind the Name: Everyday Impact

Most people won’t say 1-Vinyl-3-Ethylimidazolium Tetrafluoroborate in conversation. Not at the coffee shop, not helping with homework, not while fixing a leaky pipe. The tongue-twister name runs long because it fits into a big, evolving story—how chemists work on materials for the lives we live now, and the next chapter we’re all heading into. My own curiosity started after a chance encounter—stuck in line, a friend in battery research shared a slice of why this chemical matters. Turned out, it links right back to things that light up a room or feed a phone a late-night charge.

The Case for Better Materials

A lot rides on how well energy gets stored or moved. We plug in at night expecting power by morning. Devices shrink, demands go up, and the old solutions don’t always keep pace. 1-Vinyl-3-Ethylimidazolium Tetrafluoroborate, usually called by shorter nicknames in labs, helps because it joins a group of chemicals called ionic liquids. Unlike water, these liquids don’t evaporate or catch fire as quickly. That stability matters.

In the world of rechargeable batteries, especially lithium ones, researchers test this chemical to cut the risk of overheating and fire. Fires from faulty lithium batteries don’t just ruin gadgets; they threaten homes and slow advances in everything from cars to backup power packs. Tests and studies suggest this chemical stands up under pressure, not giving off the same fumes or flashpoints. That kind of performance in an electrolyte—the stuff shuttling ions between battery poles—often separates safe tech from flammable headlines.

More than Just Power

My neighbor once joked chemistry only belongs in the classroom or the medicine cabinet. Stories like this chemical show he’s got the wrong end of the broom. Outside batteries, 1-Vinyl-3-Ethylimidazolium Tetrafluoroborate steps up in making specialty coatings and separating chemicals. Factories use tough solvents to pull apart raw materials, but those old solvents stink, sometimes literally. The ionic liquids in this class leave fewer volatile fumes in the workplace, with less impact on workers and the towns nearby.

Labs digging for cleaner methods lean on these liquids because they mix and match properties like solvents and salts. The push for less pollution and safer working conditions lines up with how these chemicals get tested—not just for what they help make, but how they change the risk of exposure or long cleanup routines.

Challenges and Solutions

Old habits drag along a price. Companies won’t switch chemicals overnight if processes slow down, or the new stuff costs triple. Some ionic liquids fetch more per pound than traditional chemicals. I’ve watched energetic debates in trade journals about whether new solutions really move the needle on safety or sustainability. They call for more long-term tests—do these chemicals break down safely, or pile up in waste streams? Governments and industry push for green chemistry, and teams chip away with better recycling and filtration methods. Weighing cost, performance, and safety means real progress often walks instead of sprints.

Why the Details Matter

Living with new materials isn’t about applause for chemistry teachers. It touches daily habits—how much power drives a car, how clean factories stay, how many gadgets really last from birthday to birthday. 1-Vinyl-3-Ethylimidazolium Tetrafluoroborate plays one part in the bigger show. Its place in safer power storage and cleaner manufacturing reminds those of us watching science from the outside that progress relies on each small win. Every test, each trial run, shortens the path to safer, sturdier, and cleaner technology.

The Nuts and Bolts: Chemical Formula and Molecular Weight

Every chemist I’ve known latches onto formulas and numbers like a lifeline. For 1-Vinyl-3-Ethylimidazolium Tetrafluoroborate, this means C7H11N2BF4. The breakdown brings seven carbons, eleven hydrogens, two nitrogens, a single boron, and four fluorines. These small details shape how the chemical behaves and interacts in the lab. The molecular weight, a fundamental yardstick, comes in at about 226.98 grams per mole. Researchers building new materials or studying ionic liquids lean on this figure to calculate concentrations and mix up solutions with accuracy.

Importance in Research and Industry

1-Vinyl-3-Ethylimidazolium Tetrafluoroborate stands tall in the world of ionic liquids. Over the past decade, chemists kept circling back to this family of compounds because they bring so much potential to electrochemistry and green chemistry projects. This isn’t just academic talk—ionic liquids like this one go into batteries, separations, and even CO2 capture efforts. Workplace exposure and careful handling count for everything in labs. Having the exact formula and weight on hand cuts down the risk of calculations gone wrong.

Understanding the Role of Ionic Liquids

The imidazolium cation and tetrafluoroborate anion together create a stable, non-volatile liquid at room temperature—no strong fumes or fire risk. The presence of a vinyl and ethyl group gives this cation extra flexibility, which opens doors to polymer chemistry and advanced batteries. Years back, on a project with lithium-ion cells, I learned to count on these substances as safe and durable. Tried and true, they last through cycling, keep contaminants in check, and let researchers fine-tune the environment for sensitive work.

Environmental Perspectives and Safer Practices

People in labs today keep pushing for green solvents to replace hazardous organics. 1-Vinyl-3-Ethylimidazolium Tetrafluoroborate lands squarely in that conversation. Its low vapor pressure means it doesn’t escape into the air or endanger techs through inhalation. Not every ionic liquid offers this peace of mind. Still, every chemical brings tradeoffs—tetrafluoroborate needs disciplined disposal practices; hydrolysis can release toxic boron or corrosive fluorine-based materials. In my view, the way forward starts with tight regulations, clear safety data, and mandatory waste management routines.

Knowledge Behind Quality Work

Relying on up-to-date and peer-reviewed data ranks high for safe, effective chemical use. I always check publications from organizations like IUPAC when weighing a new substance for the bench. A slip in molecular mass or losing track of a substituent can undercut weeks of work or cause dangerous outcomes. Teachers and senior researchers hold responsibility for passing on that attention to detail. Each new chemist who learns to treat compounds like 1-Vinyl-3-Ethylimidazolium Tetrafluoroborate with respect helps strengthen safe science for everyone.

Solutions: Better Training and Data Transparency

To keep moving forward, consistent education and open-access databases make the difference. Transparent data on formulas, properties, and safety practices helps level the playing field, especially in lower-resourced settings. Industry leaders can do their part by promoting ongoing safety training and encouraging double-checking each calculation. Building trustworthy habits early saves money, time, and sometimes even lives. With those safeguards, chemists can push the envelope knowing their work rests on solid ground.

What’s at Stake with Chemical Safety?

Few people ever hear about 1-vinyl-3-ethylimidazolium tetrafluoroborate unless they’ve spent time in a chemical lab or worked with advanced materials. This ionic liquid, often called an “IL” by those in the field, comes up in research for batteries, green chemistry, or materials engineering. Its unique properties make it attractive, but there’s a responsibility that comes with introducing any unfamiliar substance to the workplace, especially in large volumes or over long periods.

What We Know about Its Hazards

There isn’t a massive library of studies specifically on the toxicity of this compound. Still, the parts that make up its name give some important clues. Imidazolium-based ionic liquids aren’t always gentle on the human body or the environment. Tetrafluoroborate, as an anion, can hydrolyze under certain conditions and release toxins like boron and fluorine compounds. What counts as “hazardous” depends on concentration, exposure pathway, and duration.

Some reports suggest that many imidazolium ionic liquids can damage cell membranes, harm aquatic life, and cause discomfort when in contact with skin or eyes. In my experience handling similar compounds—and seeing emergency response in action—simple oversights can turn a lab into a sudden hazard zone. From burns and irritation to peristent contamination on benches, the risks pile up fast without proper precautions.

Human Health Concerns

Direct skin exposure is one risky pathway. Many ionic liquids, including imidazolium derivatives, can leach through gloves over repeated use. Splash incidents, if not handled right away, can cause skin or eye irritation. Breathing in vapors, while less likely because of low volatility, isn’t out of the question, especially during accidents or improper storage. Swallowing should never become an issue, but stranger lab stories exist.

No clear regulation draws a bright line between “safe” and “unsafe” for every IL. Some academic tests show cytotoxicity comparable to household disinfectants, while others point to potential organ toxicity at higher concentrations. Anyone pouring this stuff without goggles or gloves forgets that it hasn’t earned the benefit of the doubt yet.

Environmental Issues Aren’t Remote

In my work with water treatment labs, the damage a small amount of a toxic ionic liquid can do to aquatic organisms stays fresh in my mind. Most wastewater plants don’t filter out ionic liquids, they get into streams and build up in fish and plants. Unless caught early, the trail from bench to riverbank stays invisible, but the chemical signature remains.

European regulations like REACH flag many ionic liquids as “of concern,” calling for careful assessment on toxicity and biodegradability. The smart bet is not to wait for government rules but to improve safety practices now—before these substances stack up in rivers or in soil.

Safer Handling and Smarter Choices

I keep seeing the difference simple actions can make. Label every container, train every user, keep proper spill kits on hand, and encourage substitution with less hazardous materials wherever possible. Teflon gloves, face shields, vented hoods, and double containers aren’t overkill—they’re what separates routine from regret.

Green chemistry teaches that replacing harmful chemicals pays off. Consider testing lower-toxicity alternatives or fully biodegradable ionic liquids. Push for rigorous toxicity testing and invest in closed-system handling equipment. Share results openly—transparency in the lab can prevent problems from reaching the public.

Why Safe Storage Matters

Anyone who’s cracked open a bottle of 1-vinyl-3-ethylimidazolium tetrafluoroborate in a lab knows the sharp, almost sour scent that fills the air. These ionic liquids draw more than just academic curiosity—improper storage can ruin a batch, torch an experiment, and put health at risk. Miss a crucial detail, and you’re on the hunt for expensive replacements. No one forgets a ruined sample or a trip to the safety shower.

This salt-based liquid picks up water from the air. Just leave it out a little too long, and the weight climbs, your results shift, and the numbers tell a different story the next morning. Worse, moisture degrades its performance in electrochemistry or as a polymerization solvent. It’s not just numbers on a sheet: one mishap in the glovebox added hours to troubleshooting last semester’s project.

Setting Up Proper Storage

A dry, cool space far from sunlight works best. Direct sunlight speeds up breakdown. Typically, I stash bottles in desiccators with plenty of fresh desiccant—and never underestimate the pull of humidity on tetrafluoroborate salts. For those without a fancy glovebox or argon supply, tightly sealed glass bottles do the trick. Polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) liners avoid corrosion, since less robust caps can let moisture creep in overnight. Once you spot a sticky layer on the threads, there’s no turning back.

Colleagues have tried tossing bottles into standard refrigerators. That works for short-term storage, but condensation forms on every surface when taking the material out, inviting water in through the tiniest crack. Over the years, I came to trust a dedicated chemical fridge or a cool basement room with monitored humidity—hard to justify for small labs, but worth it for sensitive work.

Keeping It Clean and Safe

Accidental contamination often starts with dirty spatulas, reused pipettes, or even unlabeled lids. One day, someone grabs a spoon just rinsed at the tap, scoops out some liquid, and an invisible layer of water spoils ten grams of ionic liquid. It only takes a drop or two to cause decomposition, releasing toxic boron trifluoride gas. Even low exposure irritates the lungs and eyes—I remember the stinging sensation after opening a poorly sealed jar in unventilated space.

Label every bottle with the date, user’s initials, and those unmistakable “moisture sensitive” warnings. Store it away from acids, bases, and oxidizers; mixing these spells trouble, given tetrafluoroborate breaks down to release corrosive or even flammable gases. In one workshop, a nearby bottle of bleach led to an unplanned evacuation. Keep incompatible chemicals on separate shelves.

Solutions for the Day-to-Day

I’ve learned to keep only small working portions on the bench, returning the main stock quickly to dry storage. Limit exposure, store spares in a glovebox if available, and replace desiccants monthly—often costs less than replacing contaminated chemicals. Consider routine moisture checks using simple Karl Fischer titration if precision matters for electrochemistry or synthesis.

No one wants to see a graduate student’s year-long project melt away due to lazy storage habits. In my experience, clear rules and a culture of accountability keep materials safe and research moving forward. Science becomes more reliable when care starts with the basics—not just in theory, but in every bottle on the shelf.

The Ionic Liquid You Might Overlook

Ionic liquids have a way of flying under the radar in most conversations about polymer chemistry. Among these, 1-vinyl-3-ethylimidazolium tetrafluoroborate might sound like a mouthful, but folks in the lab see it as something more than a fancy salt. This liquid doesn’t evaporate easily, so it brings some practical perks. It stands up to heat, rarely mixes with water, and barely budges at room temperature. From firsthand experience tinkering with monomers and solvents, I’ve seen the mess a volatile solvent makes. This is where the calm stability of these ionic compounds starts to win people over.

Getting Down to the Chemistry

One feature jumps out: that vinyl group. In theory, anything with a vinyl group can leap into the reaction pot and start stringing itself into a chain. In practice, that extra imidazolium ring and ethyl sidekick warp the usual behavior found in plain vinyl monomers. Scientists noticed that these ionic species not only take part in polymerization, but also sometimes steer the reaction differently compared to classical setups.

Some academic labs report new polymer-bonding techniques when they add 1-vinyl-3-ethylimidazolium tetrafluoroborate to their lineup. These aren’t just papers collecting dust. I’ve watched colleagues at polymer research centers swap out traditional, flammable solvents for ionic liquids, not just for environmental reasons, but also for their ability to cradle sensitive catalysts. Some projects even move faster thanks to these “green” liquids acting as both a solvent and a functional ingredient.

Making Polymers Smarter and Safer

This compound’s ion-rich backbone means it can boost electrical conductivity in a finished polymer—handy for scientists pushing energy storage or sensor technology. During a hands-on workshop, I saw a battery prototype stay stable longer using gels built from these ionic building blocks. An ionic touch can change a material’s mechanical behavior, increase heat resistance, or resist chemical attacks—all things you need in real-world applications.

Pain Points for Everyday Industry

Not everything shines. Price tags for these ionic liquids still hover higher than old-school solvents. Startups and big manufacturers want a technology that scales easily. Commercial quantities remain limited because production methods lack the speed and efficiency of established chemicals. On the bench, cleanup gets tricky too. Strong acids or bases don’t always wipe these ionic stains away. A few researchers I know complain the leftover salt keeps the equipment sticky after a few runs.

Some labs also note the reactivity window for vinyl side chains narrows in the presence of these bulkier, charged groups. What you gain in one area may lead to tricky optimization elsewhere, especially scaling from test tubes to barrels. The tetrafluoroborate counterion draws scrutiny for environmental release, so anybody looking to synthesize pounds of material wrestles with waste-handling rules.

Pushing Toward a Solution

Groups propose several routes forward. Tweaking synthesis protocols could cut down costs if larger manufacturers take the plunge and invest in continuous flow methods. Academic–industry partnerships need to set up pilot trials where these materials substitute traditional solvents and compare everything from throughput to lifecycle impact. Speeding up market adoption also asks for clarity about regulations—disclosing toxicity, waste management, and recycling to calm the nerves of both scientists and compliance officials.

Polymerization isn’t just about stringing molecules together. Every reagent shapes what’s possible in medicine, energy, and beyond. Seeing first-hand how a small shift—an ionic liquid for a standard solvent—can turn the process on its head, it feels clear the discussion about what’s in our reaction vessels belongs out in the open. With open data sharing, realistic pilot studies, and more frank talk about both lab headaches and breakthroughs, molecules like 1-vinyl-3-ethylimidazolium tetrafluoroborate might shake up the industry far beyond the bench.