1-Vinyl-3-Methylimidazolium Bis((Trifluoromethyl)Sulfonyl)Imide: A Comprehensive Commentary

Historical Development

Chemistry often walks a long road before turning out solutions that change the way industries work. Over the last two decades, ionic liquids gained attention as solvents, electrolytes, and reaction mediums. Among the most researched, 1-Vinyl-3-Methylimidazolium Bis((Trifluoromethyl)Sulfonyl)Imide, sometimes known by its shorthand name, has its roots in the search for green alternatives to volatile organic compounds. Early research in the 1990s focused on quaternary ammonium salts, but scientists soon realized the imidazolium ring, with its asymmetric nitrogen atoms, carried performance advantages. Introducing the vinyl group provided a route to polymerizable ionic liquids (PILs), driving a wave of patents throughout the 2000s. As energy researchers, myself included, looked for non-conventional electrolytes for batteries and capacitors, the bis((trifluoromethyl)sulfonyl)imide anion, often abbreviated as TFSI, offered outstanding chemical and thermal stability compared to earlier halide counterparts. Academic and industrial teams started to see promising advantages, both in electrochemical performance and in opportunities for new materials design, which shaped the current demand for this specialized salt.

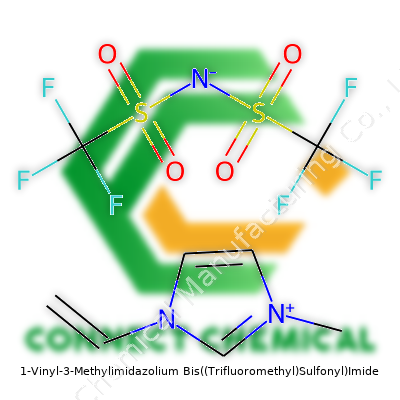

Product Overview

The structure of 1-Vinyl-3-Methylimidazolium Bis((Trifluoromethyl)Sulfonyl)Imide reveals why it keeps grabbing the attention of research labs and industrial process chemists. Sporting a vinyl group attached at the first position of the imidazolium core and a methyl at the third, the molecule behaves as a liquid at room temperature under most atmospheric conditions. This product’s ionic character, stemming from the imidazolium cation coupled with the large, weakly coordinating TFSI anion, brings an unusually low melting point and superb ion mobility. Off-the-shelf suppliers usually deliver a faintly colored liquid, typically colorless to pale yellow, which speaks to its relative purity. Some of the earliest samples I worked with exhibited only trace water content, though the hygroscopic tendency calls for careful handling. Use in energy storage and catalysis circles often dominates discussion, yet the possibilities spill into polymer science, biochemistry, and material engineering.

Physical & Chemical Properties

Talking about physical and chemical characteristics, 1-Vinyl-3-Methylimidazolium Bis((Trifluoromethyl)Sulfonyl)Imide stands apart from other ionic liquids. The combination of a flexible organic cation and the massive TFSI anion brings the melting point down to roughly −10 to −20°C in pure form, allowing storage and handling under room temperature for most lab and industrial conditions. Its density comes in at about 1.4–1.6 g/cm³, heavier than water but manageable in most setups. Boiling points generally stay undisclosed since decomposition occurs before boiling, typically between 350°C and 400°C, as observed during thermal gravimetric analysis. Viscosity sits in the moderate range (roughly 100–200 centipoise at 25°C), making pumping and mixing practical without excessive force. The negligible vapor pressure means no significant loss or exposure, one of the main health and safety advantages compared to conventional volatile liquids. Solubility ranges widely—this salt dissolves without fuss in polar solvents but resists dissolution in most nonpolar solvents. Electrochemical stability windows often extend above 4.5 V, which matters directly in battery and supercapacitor applications.

Technical Specifications & Labeling

Suppliers catering to serious researchers provide thorough documentation for this compound, often listing CAS number 174899-66-2 and standardized batch certification. Quality specifications flag water content, halide impurities, and organic contaminants; for example, top-tier samples keep water well below 200 ppm to preserve electrochemical performance. Labels must reflect the substance’s hazards and regulatory information—Globally Harmonized System (GHS) pictograms highlighting irritation and aquatic toxicity remain standard. Typical containers feature amber glass or fluoropolymer bottles, as some plastics show compatibility concerns with ionic liquids. As an operator, I always insist on double-checking manufacturing dates and batch numbers, given the sensitivity of many downstream applications to moisture and degradation products.

Preparation Method

In practice, synthesis usually follows a multi-step approach. A classic pathway starts with 1-methylimidazole, reacting with vinyl halide (such as vinyl bromide) to form the quaternary imidazolium salt. Controlling temperature and inert atmosphere guards against unwanted polymerization during alkylation. The resulting 1-vinyl-3-methylimidazolium halide then goes through a metathesis—mixing with lithium or sodium bis((trifluoromethyl)sulfonyl)imide in deionized water. Stirring over several hours, the ionic liquid phase separates due to hydrophobicity, followed by repeated washing with water and sometimes activated carbon to scrub off residual halide and organics. Final drying under vacuum or inert gas, often at mild heat, achieves samples with water content low enough for demanding research. Batch variability can turn significant based on the purity of starting reagents and care during washing; once, minor neglect in the washing step introduced enough halide to sabotage electrochemical results, so attention during cleanup never gets skipped.

Chemical Reactions & Modifications

The vinyl group opens doors for further chemistry—mainly, radical-initiated polymerization. This monomer undergoes free-radical or controlled polymerization (such as RAFT, ATRP, or NMP), producing polyelectrolytes with ionic character along the chain. Cationic ring-modifications allow functionalization for bio-applications, sensors, or catalysis. In my own group, we explored ‘click’ chemistry to link functional moieties to the imidazolium core, tuning hydrophilicity and binding selectivity for sensor applications. Anion exchange often gets revisited—swapping TFSI with other bulky or fluorous anions nudges properties like conductivity or solubility. Some colleagues venture into grafting the ionic liquid onto silica, graphene, or polymer backbones, yielding robust, tuneable hybrid materials for membranes or electrodes. Side reactions—such as Michael additions to the vinyl site—sometimes surprise unwary chemists, particularly those who overlook the reactivity under basic conditions.

Synonyms & Product Names

Besides the IUPAC systematic name, chemists and suppliers shorten the identity to [Vmim][TFSI], VMI-TFSI, or simply Vinyl-MIM TFSI. The ionic liquid trade carries more than a dozen naming conventions, and I’ve encountered variant spellings on catalogs from North America, Europe, and Asia. Some suppliers reference it as 1-vinyl-3-methylimidazolium bis(triflylimide), or use abbreviations like ILV-13-TFSI, emphasizing batch traceability and labeling tweaks for local chemical regulations. In collaborative projects, comparing synonyms prevents miscommunication that could waste weeks on the wrong compound.

Safety & Operational Standards

Lab teams working with 1-vinyl-3-methylimidazolium TFSI consult safety data sheets before each use and memorize its main hazards—skin and eye irritation, aquatic toxicity, and slipperiness when spilled. I insist on basic PPE: nitrile gloves, safety goggles, and lab coats. Spills clean up with absorbent pads; we decontaminate all touched surfaces with isopropanol or ethanol. Waste streams require collection via halogenated organic waste controls, never down the drain. Regular training stays in place, as slow, cumulative exposure to ionic liquids stirs health concerns. Good ventilation and moisture-controlled storage—often over molecular sieves—help contain risk and preserve sample integrity. Unused or waste product needs clear tracking, with local authorities frequently reviewing disposal records for compliance. The industry calls for clear labeling, including pictograms, to ensure that shipping and storage meet evolving global standards.

Application Area

Most uses show up in cutting-edge materials and electrochemical research labs. This ionic liquid finds itself serving as a monomer in polymer electrolytes for batteries, supercapacitors, and fuel cells—industries nipping at the heels of lithium-ion innovation. Others blend it into membranes, separating ions with much higher selectivity than classical polymer films. In organic synthesis, it acts as a non-volatile solvent for green chemistry, bolstering reaction rates and product yields, and simplifying product isolation. Recently, labs deployed it as a support for catalytic systems or as a medium for enzyme reactions, given the weakly coordinating anion rarely interferes with active sites. Some early reports detail its ability to dissolve cellulose and biopolymers, making it a contender in sustainable materials. During my time helping a startup, we developed sensors and actuators by combining its polymerized form with nanomaterials for flexible electronics, withstanding repeated bending and thermal cycling.

Research & Development

Work on 1-vinyl-3-methylimidazolium TFSI hasn’t plateaued. Current research orbits around safer, more stable battery materials, aiming to improve both ionic conductivity and electrode interface compatibility. Colleagues devote attention to reducing cost and environmental footprint in the synthesis, chasing solventless or continuous-flow processes. Synthetic chemists dig into new functionalizations, building blocks for smart polymers or targeted drug delivery. Modeling teams probe ion transport and coordination structures in silico; improved computation let us predict new uses well before lab work begins. Academics partner with industrial teams to upscale production, optimize recycling, and push product reliability to levels that encourage regulatory approval for medical or food-contact uses. Multidisciplinary research—combining polymer, electrochem, and sensor experts—has yielded hybrid devices with unique capabilities, many of which wouldn’t have been possible with older solvent systems.

Toxicity Research

Early studies brought optimism, suggesting ionic liquids offered a less hazardous alternative to traditional solvents. Deeper investigation changed the conversation: chronic exposure stunts algal growth, disrupts aquatic invertebrates, and creates long-term risks via bioaccumulation. In our labs, dedicated environmental safety teams conduct regular soil and water toxicity assays, informed by ongoing university research hinting at low but persistent toxicity for imidazolium species, especially toward Daphnia magna and other test models. Luckily, the TFSI anion appears less bio-reactive than halides, but precaution remains advised until more long-term, real-world data comes in. Researchers look to maintain a closed-loop system for waste treatment, recognizing that even trace releases can pile up over decades. Accurate hazard labeling and safe disposal protocols mean nothing gets left to chance. Ongoing collaborations with ecotoxicology departments help define safer analogs and remediation routes.

Future Prospects

The drive for sustainable tech hinges on new materials that deliver stability, safety, and performance—often at odds with one another. 1-vinyl-3-methylimidazolium TFSI’s unique set of features ensures it stays in the running for next-generation electrolytes, membranes, and specialty polymers. Next steps include more cost-effective synthetic methods, thorough lifecycle assessments to minimize environmental impact, and full-scale recyclability studies. As regulatory barriers tighten, science must pivot towards designing safer analogs retaining the best properties while shedding long-lived toxicity. Experience tells me collaborative research offers the clearest path forward, uniting synthetic, physical, and biological chemists under one roof. With government incentives and cleaner tech investments, this compound’s role looks set to expand, both in research and in products that touch everyday lives.

More Than Just a Chemical Name: A Key Player in Modern Chemistry

Ask someone about 1-Vinyl-3-Methylimidazolium Bis((Trifluoromethyl)Sulfonyl)Imide, and you’ll probably find a blank stare. Outside university labs and certain industry circles, this compound barely gets a mention. Still, this molecule works behind the scenes in some of the biggest breakthroughs of recent years, especially in the world of ionic liquids.

Why Persistent Interest in Ionic Liquids?

Ionic liquids—salts that stay liquid at low temperatures—shift how scientists think about reactions and materials. The structure of 1-Vinyl-3-Methylimidazolium Bis((Trifluoromethyl)Sulfonyl)Imide fits right into this movement. People prize these substances for their ability to dissolve a wide range of compounds, combine easily with polymers, and stay stable under heat. That’s ideal for processes that want better safety, lower energy waste, and less pollution.

A study from the journal Chemical Reviews points out that ionic liquids with imidazolium cations, just like this one, pop up in research on both green chemistry and energy storage. The actual trace I see in my work is not only in creativity but also in clear benefits, such as replacing volatile organic solvents in extraction, catalysis, and separation.

Polymer Chemistry Just Got Easier

Working in a lab, you get tired of plastics that crack, lose color, or fall apart in sunlight. Additives don’t always help. But stir in 1-Vinyl-3-Methylimidazolium Bis((Trifluoromethyl)Sulfonyl)Imide during polymerization, and you often get plastics that behave better. The vinyl group means it links right onto polymer chains, making new families of ion-containing polymers. These new materials might carry current better, feel softer, or withstand higher temperatures—a win for batteries, flexible electronics, and coatings that refuse to break down.

Learning from Real Industry Choices

I once watched an engineer wrestle with a lithium battery that just wouldn’t survive testing in high humidity. Electrolytes made from common solvents were to blame. They swapped in an ionic liquid, leaning on this exact compound, for its low vapor pressure and strong resistance to water. Battery performance went up, risk dropped, and the engineer got some extra sleep for once. The numbers back it up: a Nature Energy paper found ionic-liquid electrolytes lower battery flammability and extend device lifespan.

Challenges That Are Hard to Ignore

Of course, not every solution is perfect. Making complex ionic liquids, including 1-Vinyl-3-Methylimidazolium Bis((Trifluoromethyl)Sulfonyl)Imide, takes expensive raw materials and produces waste you can’t just pour away. Researchers are still searching for cheaper, greener ways to build these molecules. And while reports show many ionic liquids offer low toxicity, the environmental impact of trifluoromethylsulfonyl groups demands careful consideration. Science needs to continue pushing for clean production and recycling options.

Finding Smarter Paths Forward

Adoption can quicken if more companies share data on long-term effects and disposal. Government policy also matters. Incentives for green chemistry help turn early research into practical solutions. Smoother paths for testing and approval could make the most promising ionic liquids easy choices for industry, labs, and even consumer products. Looking at the growth in battery-powered technology and eco-friendly plastics, compounds like 1-Vinyl-3-Methylimidazolium Bis((Trifluoromethyl)Sulfonyl)Imide stand ready for an even bigger impact. The nuts and bolts are here; it’s now a question of how quickly we can scale up, clean up, and open new doors for safer, smarter chemical design.

What We Know About This Chemical

It’s easy to see why a mouthful like 1-Vinyl-3-Methylimidazolium Bis((Trifluoromethyl)Sulfonyl)Imide, or simply VMI-TFSI, doesn’t end up in everyday conversation. But you will spot it in research labs, sometimes even in the development of batteries or green solvents. Chemists like myself meet this family of ionic liquids more often than we'd like to—usually from the other side of a fume hood.

People want safer, greener alternatives to old-school solvents. Ionic liquids such as VMI-TFSI come up often because they don’t evaporate quickly or set off big fire hazards like ether or acetone. Just because it doesn’t burn easily doesn’t mean it goes easy on your skin or lungs. Many ionic liquids carry toxic and corrosive properties. The fluorine family on this one makes it no exception.

Personal Stories from Handling Chemicals

I remember watching a colleague splash a small drop of a related imidazolium compound on their glove. The look of relief when they realized their gloves held up—and the panic before checking—sums up daily reality. Touching or breathing in these compounds isn’t the quickest route to illness, but long-term exposure risks pile up. You won’t smell any warning signs: No strong stench, no instant dizziness. That false sense of safety can trick even experienced lab workers.

Known Risks and Documentation

Safety Data Sheets (SDS) often flag VMI-TFSI for causing skin and eye irritation. Contact around mucous membranes can sting. Breathing in dust or vapors brings trouble, too. Some studies on similar ionic liquids suggest minor to moderate toxicity toward aquatic life. Allowing improper disposal means risking environmental harm over time. The jury’s still out on long-term risks for workers, but research so far calls for respect, not recklessness.

Trifluoromethyl groups in this molecule make it more stable and persistent in the environment. That sounds good for performance but bad for breakdown. If you spill some down the drain, it likely goes on traveling and accumulating. Labs are starting to take that part much more seriously now.

What Works for Safer Handling?

From experience, the right gloves, closed shoes, goggles, and long sleeves do most of the heavy lifting for personal protection. Keeping everything under a ventilated hood ensures vapors do not linger. Closed containers and minimal handling cut down on spill chances. Workers sometimes let their guard down with less familiar chemicals—yet every new material should get as much attention as chloroform or sulfuric acid.

Labs with transparent, up-to-date chemical inventories prevent unwanted surprises. Training every newcomer to ask questions early, and not just assume “newer equals safer,” separates careful labs from careless ones. Regular review of safety procedures, and adapting them whenever new research comes out, keeps a workplace honest. No shortcut replaces awareness or proper housekeeping.

Room for Improvement and the Road Ahead

Industry can push for stronger labeling and easier access to toxicity studies. If manufacturers publish clear data, chemists make smarter decisions—no more guessing or relying solely on protective gear. Environmental regulators have a chance to play catch-up, ensuring waste from labs and pilot plants gets tracked and treated with the same care as older hazardous substances. Until tougher rules or breakthrough research provides answers, every bottle of VMI-TFSI deserves careful respect. Science may give us new tools, but safety comes from human caution.

Understanding the Real Impact of Storage Conditions

A lot of folks glance at storage instructions and move on. Maybe the label says "keep in a cool, dry place" or "store away from direct sunlight." These aren’t toss-away lines. Poor storage can leave products less effective, sometimes outright unsafe. If you’ve ever reached for a snack, only to find it stale or moldy, you know frustration first-hand. That same disappointment shows up in other sectors—medicine, cosmetics, even cleaning supplies—when storage details get overlooked.

Why Temperature Matters More Than Most Think

High heat messes with more than chocolate bars and dairy. Exposure to sunlight or temperatures above room level can mess up chemical structures, cause oils to go rancid, or turn helpful enzymes useless. I once watched a friend keep asthma inhalers in their car over summer. You can bet those inhalers didn’t work as intended. For most medications, room temperature means somewhere between 20 to 25°C. Anything above that brings real risk of spoilage.

Moisture and Humidity: The Quiet Spoilers

Even a little dampness kicks off mold, clumping, or packaging failure. In my kitchen, a bag of rice left open during the wet season turned chalky and smelly in days. On a bigger scale, pharmaceutical tablets exposed to humidity break down, losing their original shape or potency. Food items fare no better. Bread in a humid pantry turns soggy and grows fuzzy stuff—bread mold loves moisture. Storing such products in airtight containers, or at least in a dry space, keeps them safe, tasty, and reliable.

The Role of Light and Air

Sunlight looks harmless but packs enough energy to shift how ingredients react with each other. Photodegradation strips color, flavor, or even healing power from products. A bottle of vitamin C left on a sunny windowsill quickly turns brown and loses punch. Oxygen in air spells trouble too. Some products oxidize—think of apples that brown after being cut. Sealing airtight after each use and picking light-protected packaging go a long way to keep things fresh.

Cleanliness Counts

Dirty storage areas welcome pests, bacteria, and cross-contamination. Years ago, I learned a tough lesson after finding weevils in my baking flour. Stacking goods on old wooden shelves where the bugs already lived gave them free lunch. Keeping storage spaces clean, wiping up spills fast, and rotating stock stops unwanted guests or spoilage before it starts. It sounds simple but many households and even some small businesses skip this step.

Accountability and Clear Instructions

Labels should spell out real requirements—actual temperature ranges, warnings about light or moisture, and what to do after opening. Companies who take store conditions seriously show they care about product safety, not just sales. For households and businesses, sticking to those directions saves money and health. I keep thermometers in my pantry and medicine cabinet for peace of mind, and I check labels every time I buy a new cleaning spray or pack of vitamins.

Practical Steps for Better Storage

Choose containers that close tight and keep products off the floor. Avoid locations near stoves, windows, or damp pipes. Read packaging, follow through on the advice, and review storage areas seasonally. Small habits—like recording open dates or keeping a checklist—keep things organized. These simple steps bridge the gap between safe, effective products and wasted money or preventable risk. Once you take control of storage, plenty of headaches disappear.

Why Chemical Structure Matters

I remember the first time I saw a chemical diagram in school. A jumble of lines, some letters, and a bunch of numbers peppered throughout—at first glance, chaotic. Then the teacher drew glucose on the board, C6H12O6, and explained how a handful of atoms, arranged the right way, can become the fuel coursing through human veins. The layout of atoms and the connections between them form a fingerprint for each compound, and chemistry lets us unlock their identities.

Every medicine, plastic, or cleaning product began as an idea, then a drawing—carbon, oxygen, nitrogen, and hydrogen forged into shapes that decide everything from solubility to safety. For example, water, H2O, seems simple. But swap one oxygen for sulfur, and you have hydrogen sulfide—dangerous and foul-smelling. A single step on the chemical structure chessboard replaces something harmless with something hazardous.

How Scientists Use Chemical Formulas

Chemical formulas don’t just sit in textbooks. They warn doctors if a drug will clash with other meds or break down in the wrong part of the body. Farmers use formulas to choose which fertilizers might release too much nitrate. In environmental labs, analysts read formulas to see if a compound will linger in the soil, pollute rivers, or vanish harmlessly in sunlight.

Take aspirin: C9H8O4. Its structure gives it pain-fighting power. Chemists noticed that small tweaks—changing positions or groups on the molecule—create cousins like acetaminophen (C8H9NO2), hitting different pain or fever targets. Knowing the structural difference allows doctors and patients to choose the right medicine.

Challenges and Solutions

Drawing and reading chemical structures takes training. A wrong line or misread letter can send a project tumbling. Mistakes cause delays in drug discovery or safety testing. Early in my lab work, I mistook a methyl group for an ethyl, skewing results until a senior scientist caught the blunder. Simple errors in structure matching can cost labs time and money.

One way out involves technology—software that double-checks structures as you draw them. Databases and digital libraries let scientists search by structure, not just name, so people across the world can talk about the same molecule. Education plays a role as well. Learning the basics of chemical drawing and recognition sets up students and scientists for fewer mistakes and faster breakthroughs.

The Big Picture

Chemical formulas pack deep information into a string of letters and numbers. You see C8H10N4O2, chemists see caffeine, with its familiar jolt for coffee drinkers everywhere. Behind every new discovery lies a structure—tested, tweaked, sketched, and eventually trusted. That sits at the core of discovery, safety, and the search for smarter solutions. Each compound’s formula points the way to its purpose, its promise, and its potential dangers, if any. A sharp eye for chemical structure keeps new materials, medicines, and solutions not just possible, but safe and reliable for everyone who counts on them.

Recognizing the Risk

Walking through a research lab, I’ve seen how even a splash of something unfamiliar brings a group together. 1-Vinyl-3-Methylimidazolium Bis((Trifluoromethyl)Sulfonyl)Imide, or [VMIM][TFSI], gets called an “ionic liquid”—these belong to a group of chemicals prized in advanced batteries and modern syntheses. With all those uses comes the flip side: what to do with the leftovers.

This isn’t baking soda. Ionic liquids don’t evaporate or break down quickly. They often carry a reputation for low vapor pressure and chemical persistence. For folks who think tossing the remains in the sink works, the pollution risk runs high. Fluorinated sulfonyls, like those in TFSI, stick around in the environment and resist most biological or chemical attacks. Wildlife doesn’t have a fix, either. These chemicals gather over time, especially in water or soil, and that can mean trouble down the food chain.

Understanding Regulations and Responsibility

No single rulebook says “do this” for [VMIM][TFSI]—which means clear local practice is a must. State environmental laws in the US and EU chemical safety rules don’t treat these as household trash. I’ve watched older chemists take their time reading Material Safety Data Sheets before even handling the stuff. Any solutions to managing these ionic liquids must always consider their full chemical makeup since “ionic liquid” covers hundreds of compounds with different dangers.

Concrete Steps for Safer Disposal

People in labs learn early: designate a special waste container, keep it labeled, and keep it shut. Don’t pour this chemical down a drain or toss it in regular trash. Find a waste service licensed for hazardous, halogenated organics. They batch these chemicals and burn them inside special incinerators—systems running at temperatures high enough to break down resistant bonds and destroy the structure of those tough fluorinated rings. Open burning or back-alley dumping creates a risk of releasing toxic gases or leaving residues behind. Facilities designed for this task control the process and vent off only what environmental laws allow.

Waste audits help, too. If you work in research, track quantities and encourage sharing leftovers before disposal. I’ve seen electronics labs set up exchanges, so a few grams here or there get re-used. It might not sound like much, but it keeps the disposal stream lighter.

Better Habits, Smaller Footprint

Long-term, the best solution means less waste at the start. Reduce the scale of experiments. Use only what’s needed. Ask vendors for greener alternatives. Some ionic liquids can be recycled or purified, although not every operation pulls this off. A few research groups recover and re-distill spent solvents. Training new staff on safe handling and disposal prevents mistakes and keeps everyone accountable.

Create a Culture of Safety

Trust depends on more than following the rules—it grows from routine habits. Lab leaders who share the why, not just the how, help build a group where waste isn’t ignored after the work is done. Each small act to manage hazardous chemicals means fewer headaches years down the road. People remember their worst spills, but safer handling means fewer stories to admit and a healthier environment at the end of every project.

If there’s one thing the labs and factories taught me, it’s that taking safe, practical steps pays off. Looking out for each other—and the world beyond the lab walls—always matters.