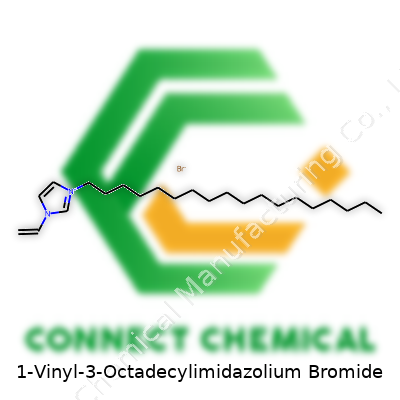

1-Vinyl-3-Octadecylimidazolium Bromide: A Detailed Commentary

Historical Development

The story of 1-Vinyl-3-Octadecylimidazolium Bromide lines up with the evolution of ionic liquids and functionalized imidazolium compounds. Back in the 1970s, scientists dove into imidazolium salts for their potential in non-volatile applications, and their use grew across chemistry labs, fueled by research into green solvents and alternative electrolytes. This compound, with both a long-chain alkyl group and a vinyl functional group, marks a step forward, merging hydrophobic characteristics and polymer-ready functionality. Taking a first look at its structure, many years ago, I remember being struck by its clever balance of tunable properties, especially useful for surfactant science. Over time, this led to rising interest from polymer chemists and researchers aiming to tailor material surfaces or create new ionic polymers.

Product Overview

1-Vinyl-3-Octadecylimidazolium Bromide blends a vinyl group, ripe for polymerization, with a hefty C18 alkyl tail, offering unique amphiphilic behavior. What you get is an organic salt, generally crystalline with a white or off-white appearance, carrying the properties of both an ionic liquid and a surfactant. The product appeals to those who crave a charged yet hydrophobic surfactant ready for modern synthesis. Each batch typically holds up well under ambient conditions, though sealed storage supports best stability.

Physical & Chemical Properties

With a molecular formula of C27H47BrN2, the salt shows a high molar mass compared to simpler imidazolium analogs. Its melting point generally ranges from 80–120°C, heavily influenced by sample purity and water content. The compound stands out through strong thermal stability and pronounced surface activity, meaning that just a little can impact the wetting, emulsification, or stabilization of other materials. The long aliphatic tail resists quick integration into polar solvents, so you’ll see selective solubility—miscible in chloroform and similar organics, but only sparingly soluble in water. The vinyl group on the ring isn’t just decorative; it acts as a reactive seat, making the salt a direct candidate for radical polymerization or cross-linking reactions.

Technical Specifications & Labeling

Labeling this product starts with the IUPAC name: 1-vinyl-3-octadecyl-1H-imidazol-3-ium bromide. Sample purity from reputable suppliers often runs above 98%, documented by proton NMR and mass spectrometry. Handling guidelines emphasize wearing gloves and goggles due to the potential for skin and eye irritation. Each bottle typically carries full hazard labeling, storage instructions, and a certificate of analysis for lot-specific quality. In the package insert, you’ll often find measured water content and a CAS number, which aids in regulatory tracking and inventory.

Preparation Method

Making 1-Vinyl-3-Octadecylimidazolium Bromide usually starts with 1-vinylimidazole and 1-bromooctadecane. In a round-bottom flask, a mixture of the two in acetonitrile or another polar aprotic solvent heads onto gentle reflux. Over several hours, high yields of quaternization result if the alkyl bromide content remains in slight excess. After cooling, solvents leave, and the crude salt receives several washes to remove unreacted precursors and byproducts. I’ve noticed the purification routine can make a real difference—careful re-precipitation and drying under vacuum keeps byproducts at bay, leading to a fine, almost waxy crystalline solid that stores well if moisture stays away.

Chemical Reactions & Modifications

Chemists value this salt for what the vinyl group allows. Using free radical initiators like AIBN, the salt chains up easily with acrylates or styrene to form tailored polyelectrolytes or surface coatings. Its long-chain alkyl tail offers hydrophobic modification opportunities on otherwise hydrophilic surfaces. Because the imidazolium ring supports a range of alkylations and cross-linking, researchers often explore post-polymer modifications or swap the bromide for another anion via metathesis. The salt can even form complex assemblies or micelles in selective solvents—the rich chemistry draws people interested in both materials innovation and fundamental self-assembly science.

Synonyms & Product Names

The compound goes by several names. In catalogs, you’ll see monikers like 3-Octadecyl-1-vinylimidazolium bromide or N-Octadecyl-N'-vinylimidazolium bromide. Suppliers may also list it as C18-vinylimidazolium bromide or by shorthand like [C18VIm]Br. Different nomenclatures all point to a molecule combining vinyl and C18 chains on the imidazolium backbone, distinguished by its crystalline form and reactive vinyl site.

Safety & Operational Standards

Handling this chemical presses on issues familiar to everyone working with quaternary ammonium or imidazolium salts. Protective clothing and chemical splash goggles stop inadvertent irritation or sensitization. MSDS sheets outline risks associated with ingestion or prolonged skin exposure. I always stress good ventilation—though the salt itself lacks high vapor pressure, off-gassing from solvents or byproducts could cause discomfort in small workspaces. Storage away from strong oxidizers and moisture minimizes degradation and keeps the product safe for longer spans. Disposal of waste aligns with local rules for halogenated organics, a necessary point for labs worried about environmental compliance.

Application Area

The versatility of 1-Vinyl-3-Octadecylimidazolium Bromide stretches across several fields, thanks to that dual character of ionic charge and hydrophobic tail. You’ll meet it in the world of polyelectrolyte synthesis, where both anti-static coatings and ion-conducting membranes find use for custom ionic domains. It pushes boundaries in dispersing agents for nanoparticles, as the ionic liquid structure tempers agglomeration even with tricky materials. I’ve watched researchers develop antimicrobial coatings by exploiting the long alkyl chain’s disruption of microorganism membranes. Surface stabilization in colloidal systems, emulsion polymerization, and even smart hydrogels all draw on the salt for specialty design. Battery researchers, too, pay attention—polymeric ionic liquids formed from these salts enable fresh looks at solid electrolyte performance and interface compatibility.

Research & Development

R&D with this molecule keeps pulling in chemists and material scientists. Each new published method expands what’s possible, from controlled radical polymerization to anion-exchange protocols that tweak solubility and mechanical strength of resulting films. Designing block copolymers with both imidazolium-bearing and neutral blocks enables fine-tuned responses in smart materials. Many groups now pair the salt with emerging nanomaterials, aiming to boost stability or modulate electrical conductivity. Every year, fresh articles point to novel hybrid materials enabled by the salt’s unique attributes.

Toxicity Research

Toxicology studies for imidazolium-based salts remain ongoing. Experience from parallel quaternary ammonium compounds and ionic liquids points to moderate acute toxicity and some risk of irritation on repetitive skin contact. Long alkyl chains can boost hydrophobicity but occasionally raise issues around bioaccumulation or environmental persistence. I always suggest reviewing updated data sheets; many regulatory panels classify the salt as hazardous until more full-spectrum testing concludes. Biological tests on certain microbes and model organisms have shown both antimicrobial behavior and mild cytotoxicity—so safe lab practices and responsible waste handling matter.

Future Prospects

Demand for functional monomers like 1-Vinyl-3-Octadecylimidazolium Bromide only looks set to grow as material scientists chase advanced applications in energy storage, next-generation coatings, and biomedical surfaces. The combination of vinyl reactivity and tailored amphiphilicity gives this salt a seat at the table for innovation in anti-fouling membranes, soft actuators, and multi-responsive systems. I see a path forward carved by interdisciplinary teams who take the fundamentals and mix them with real-world problems—like water desalination, wearable electronics, and even flexible biosensors. Persistent green chemistry challenges, concerning safer synthesis routes and better degradability, will also attract investment and research energy, pushing the boundaries even further.

A Closer Look at This Specialized Chemical

Every now and then you bump into a name like 1-Vinyl-3-Octadecylimidazolium Bromide. It’s a mouthful with a very specific set of jobs, mostly in research and specialty manufacturing labs. This compound stands out as an ionic liquid, meaning it’s basically a salt that stays liquid at lower temperatures. I remember one of the first times I saw this kind of salt used in an experiment—no white powder, just a clear liquid in a tiny vial, ready to transform an experiment that relied on a stable and conductive environment.

Making Polymer Science Really Work

Synthetic chemists like using this compound for making unique polymers. Tossing that long octadecyl tail onto the imidazolium ring gives the resulting polymer extra length and flexibility. It helps this compound act as a template in block copolymer synthesis, which can be used to build up nano-sized structures with very predictable properties. Think of materials for high-end batteries or membranes that need rock-steady electrical properties and mechanical strength. You’d be surprised to find just how much the shape and size of ions like this steer how these advanced membranes handle ions or separate gases.

Green Solvents: Cleaning Up Industrial Chemistry

A lot of people in industry started paying serious attention to ionic liquids like 1-Vinyl-3-Octadecylimidazolium Bromide because they don’t evaporate into the air easily. Unlike old-school solvents, which can mess with the atmosphere and your lungs, this compound stays put. I remember hearing from a friend at a chemical plant who described how ionic liquids helped their firm cut industrial emissions. These chemicals let you dissolve tough substances, run smoother extractions, and keep the whole process a lot cleaner.

Nanomaterials and Smart Surfaces

Working in materials development, I’ve seen how this compound acts as a stabilizer for nanoparticles. Those long hydrocarbon tails wrap around the outside of growing particles, preventing clumping and keeping everything apart at the nanometer scale. The result: well-behaved nanoparticles that don’t just stick together into big useless clumps. Folks in electronics and coatings research lean on this because it lets them design surfaces that repel water, attract certain chemicals, or conduct electricity in unusual ways.

Earning Its Place in Research

Researchers use this compound to craft test environments for advanced batteries, fuel cells, and corrosion-resistant coatings. The imidazolium part helps transport ions while that long tail changes how well it interacts with different materials. I’ve read studies where this particular ionic liquid improved the cycle life of lithium batteries or helped separate metal ions out of wastewater. Lab teams keep looking for ways to use it to lower the cost and raise performance in new tech.

The Road Ahead

Some worries linger about cost, recycling, and large-scale supply. The good news: chemists have made progress on reclaiming and reusing these liquids. Clearer regulations and better process design can keep the risks in check. With each experiment and pilot run, 1-Vinyl-3-Octadecylimidazolium Bromide is carving out more jobs for itself in places where old chemicals fell short. The more it proves itself, the faster technology can move toward processes that are safer for people and the planet.

Understanding the Risks of Chemical Storage

Anyone who’s done lab work knows the hassle of finding a ruined batch of reagent because of poor storage. With 1-Vinyl-3-Octadecylimidazolium bromide, a specialty ionic liquid, the challenges might not look intimidating at first glance, but experience has shown me that the smallest oversight often spirals into costly setbacks. This chemical, with its long hydrocarbon chain fused to an imidazolium core, plays a unique role in areas ranging from polymerization to advanced materials. Looking at the structure, moisture and light can quietly chip away at purity and performance, so storage cannot be left on autopilot.

Keeping Moisture at Bay

Few contaminants wreck ionic compounds like moisture. Both imidazolium rings and bromide ions can absorb water directly from the air. Leave a bottle open in a humid room, and pretty soon you’ll see clumping or an odd change in texture. Even with a tight cap, ambient humidity sneaks in. I store this compound in tightly sealed amber glass bottles, inside a desiccator filled with silica gel. Plastic containers react too easily, and cheap lids often warp and leak. That extra layer—a well-maintained desiccator—makes a difference, sparing the lab the headache of having to order replacements or spend hours drying a spoiled sample.

Fighting the Effects of Heat and Light

Direct sunlight heats up bottles faster than most expect, speeding up unwanted side reactions or decomposition. Once, I left a reagent cart next to a sunny window, and by the end of the week, a handful of chemicals, including a stock of quaternary ammonium salts, had changed color and lost effectiveness. With 1-Vinyl-3-Octadecylimidazolium bromide, warmer temperatures can promote slow breakdown—especially for the vinyl group. Cool, dry storage, away from sunlight, stands out as the best bet. A refrigerator set at two to eight degrees Celsius works well, as long as bottles aren’t exposed to freeze-thaw cycles. I flag any solutions that look cloudy, and I never trust a bottle left out on a bench for more than a few hours.

Labeling and Segregation: No Half Measures

To avoid cross-contamination or risky reactions, I always keep ionic liquids away from oxidizers and acids. Good habits—such as labeling the original date, last opened date, and keeping backup inventory notes—can save a lot of grief later. Glass cabinets segmented for flammable and non-flammable compounds provide an extra level of safety. Accidentally mixing even a drop of bleach or nitric acid with bromide salts can lead to dangerous byproducts, so separating these classes is more than just best practice—it’s common sense.

Personal Experience & Industry Standards

The European Chemicals Agency and local safety guidelines both recommend low humidity, cool temperature, and using materials that don’t react with ionic liquids. Personal slip-ups, like store-room clutter and forgetting to reseal a bottle, never bode well, so every chemist in my team follows a checklist before closing up shop. Using desiccant packets and checking for cloudiness once a week maintain the compound’s utility for longer.

Simple Solutions That Work

Storing 1-Vinyl-3-Octadecylimidazolium bromide boils down to four practical steps: keep it dry, keep it cool, keep it in the dark, and keep it separate from incompatible materials. Regular checks, dated labeling, and well-chosen storage containers remove much of the worry. Since these details translate directly to research quality and cost savings, anyone working with specialty chemicals can’t afford to treat storage as an afterthought.

Everyday Chemistry, Real Concerns

People don’t wake up thinking about obscure chemicals, but many industries use substances that look like gibberish to most. 1-Vinyl-3-octadecylimidazolium bromide falls into that box. You see it floating around in research related to ionic liquids, specialty coatings, and sometimes even as part of fancy new ways to clean up pollution. Whenever a chemical sounds this technical, folks start to wonder: is it hazardous? Will it make you sick? What does it do in the real world?

What We Know About Its Toxicity

Information on this specific compound is thin compared to household names like bleach or acetone. Still, its family tree matters. This type of imidazolium salt often pops up in academic papers, and similar compounds have sometimes been flagged for toxicity. Reports show some imidazolium-based ionic liquids can cause cell damage or disrupt aquatic ecosystems, depending on their chemical tweaks. Tests show the length of the "tail"—in this case, the octadecyl segment—can increase the risk of bioaccumulation and impact water-dwelling creatures.

That said, you won’t spot buckets of this substance under your kitchen sink. Most folks stumble across it during specialized lab work or manufacturing. Nonetheless, that doesn’t mean society gets a free pass on safety just because it's not on supermarket shelves.

Making Choices with Limited Data

The jump from petri dish to everyday hazard isn’t automatic. Regulatory agencies like EPA and ECHA track similar substances and often require data on how chemicals behave in the body and the environment. One study chillingly found certain imidazolium derivatives hang around in aquatic habitats, putting aquatic insects or small fish at risk. High concentrations swallowed or inhaled will likely cause irritation at the very least, though full toxicological profiles on this specific variant are rare.

Still, a responsible approach means using what info we have. Any material with demonstrated harm to fish, algae, or invertebrates deserves a close look before ramping up production or wide use. Scientists have a habit of underestimating risk until evidence forces a rethink. That’s happened with everything from lead paint to PFAS.

Putting Precautions Into Practice

Most of my experience with laboratory chemicals boils down to one lesson: treat everything like it’s dangerous until proven otherwise. Turn the fume hood on. Wear gloves. Store it properly with other quaternary ammonium compounds. Dumping anything down the drain without understanding the outcome is just reckless. Personally, I'd rather over-prepare and waste five minutes than end up with health issues—or wildlife taking a hit.

For industries, the right path means clear labeling, investing in training for workers, and regular hazard reviews. Regulators can push for better toxicity testing through grants and rules. Scientists have started developing greener alternatives to imidazolium-based chemicals using safer, biodegradable building blocks. These might take time, but that’s a route we should keep pushing.

Keeping Trust and Transparency Alive

Chemistry shapes daily life, but trust hinges on honesty. If companies skimp on safety or don’t share risks, public faith crumbles. My belief: publish safety data, accept outside review, and talk openly with communities that might end up downstream of a factory. Only by facing these risks head-on can we give new chemistry a fair shake, without rolling the dice on well-being.

Laying Out the Chemistry

Curiosity about substances like 1-Vinyl-3-Octadecylimidazolium Bromide comes from more than just a love for long names. At its core, this compound features an imidazolium ring with a vinyl group on one end and a hefty octadecyl chain on the other. Toss in a bromide ion to balance things out, and you have a salt that shows up in research labs working on ionic liquids, advanced materials, and surfactants.

The Formula Up Front

This molecule’s skeleton consists of a vinyl group (C2H3), an imidazolium core (C3N2H4 after substitution), and a long octadecyl tail (C18H37). Put these together, remembering to keep the nitrogens and the hydrogens from the imidazole cycle, you get the full cation: C23H43N2+. The bromide brings an extra Br- anion, so the full chemical formula appears as C23H43N2Br.

Molecular Weight: Counting Atoms Matters

Determining the molecular weight starts with the building blocks:

- Carbon (C): 23 atoms × 12.01 g/mol = 276.23 g/mol

- Hydrogen (H): 43 atoms × 1.008 g/mol = 43.344 g/mol

- Nitrogen (N): 2 atoms × 14.01 g/mol = 28.02 g/mol

- Bromine (Br): 1 atom × 79.90 g/mol = 79.90 g/mol

Adding it all up lands the molecular weight at 427.494 g/mol. For folks measuring out fine powders in the lab, this isn’t just a number — it’s the base for any reaction, calculation, or experiment involving this compound.

Why These Numbers Matter to Researchers

Understanding the formula and the weight isn’t trivia. Lab chemists rely on these numbers to get things right, especially with ionic liquids, where small miscalculations ripple out fast. I remember spilling hours over a scale, double-checking amounts, just to hit the exact proportions needed for a reaction. Even a tiny error can send an experiment off track, wasting both chemicals and time. These details hold up the rest of the work.

Accuracy in reporting chemical data connects to lab safety and reliable research. Many stories begin with people assuming “close enough” is good enough, but chemicals don’t care about rough estimates. There’s no substitute for double-checking, especially when handling something as hydrophobic as this particular imidazolium salt. The long alkyl chain gives it unique features compared to shorter versions.

Addressing Challenges Facing Chemical Research

Mislabeling compounds or using unreliable sources can undermine a project’s credibility. Chemical suppliers sometimes list slightly different data or neglect to update documentation. One solution lies in adopting stricter authentication and verification standards, leaning on spectroscopic analysis and peer-reviewed data instead of taking catalog numbers at face value.

Another way to avoid confusion is to focus education and lab training not just on theory but on practical, routine measurements and documentation. Putting extra effort into teaching new researchers about the nuts and bolts keeps confidence high and mistakes low.

Final Thoughts on Building Trust in Science

Behind every chemical formula and molecular weight stands a web of trust. Reliable data makes or breaks discoveries and innovation. By cutting corners on the basics, researchers risk pulling the rug out from under themselves and their teams. Consistency, precise data, and attention to details like the ones above support both everyday research and the biggest breakthroughs.

A Chemical Best Treated with Care

1-Vinyl-3-octadecylimidazolium bromide shows up in advanced research and specialty labs for a reason. Its chemical makeup means nobody should treat it like an everyday compound. Experience in both small and larger labs tells me: risky substances can't just blend into the regular waste stream without consequences. Spills, inhalation, and long-term environmental impacts have come back to bite labs that skipped the right steps. The cost of cleaning up later, not just in money but in reputation and health, always outweighs initial convenience.

Using the Right Protections

Direct contact isn't smart or safe here. Days working with toxic and reactive materials drilled into me the need for nitrile gloves—latex sometimes just gives out. Adding in a full-buttoned lab coat and protective goggles guards against splashes. It helps to work behind a fume hood, where vapors can't wander off and settle in your lungs. If you're storing this chemical for a while, amber bottles with tight caps keep light and air out, stopping any unexpected reactions and maintaining stability. Always label vividly—future you will thank you.

What If It Spills?

No one expects a spill, but every lab tech I’ve known has faced one. Use inert absorbents like vermiculite or sand—the classic paper towel approach doesn't cut it and spreads risk around. Scoop every bit into a heavy plastic or glass container with a screw-top lid. Don’t mix with organic or flammable substances. Open flames and heat only make things worse, risking larger incidents. If in doubt, ask for backup from colleagues or a chemical hygiene officer, not just for cleanup speed but for double-checking your approach.

Waste Disposal Shouldn't Be an Afterthought

Too often, chemical waste sits on a shelf long past the end of the project. Every safety course hammers home that improper disposal becomes an environmental hazard, contaminating water or soil. Regulations treat compounds like 1-vinyl-3-octadecylimidazolium bromide as hazardous waste for a reason. University disposal programs, third-party hazmat collectors, or in-house chemical waste protocols all have a better track record than DIY dumping down the drain. Waste containers should include a clear log sheet, so mistakes don't pile up.

The Human Side of Chemical Safety

Reading stories of chemical exposure over decades, I've seen the long-term toll on people who skipped basics—burns, breathing troubles, and even subtle neurological effects. Simple things—proper gloves, waste tags, alerting team members—change the odds. Safety culture isn’t about fear, it’s about watching out for each other and respecting the materials. Encouraging new staff to ask questions reduces the likelihood that a hazardous material ends up where it shouldn’t.

Improving Practices for a Safer Future

Protocols do the heavy lifting, but regular refresher training keeps everyone sharp. Spot checks and surprise audits shouldn’t feel punitive; they catch bad habits before they get costly. Moving toward greener alternatives stays on researchers’ minds, and in the meantime, treating each step with respect avoids emergencies. Documenting disposal, sharing lessons learned, and looping in local environmental agencies all push toward safer, more responsible labs.