1-Vinyl-3-Tetradecylimidazolium Bromide: A Deep Dive

Historical Development

People started focusing on ionic liquids after the late 20th century, once they saw traditional solvents harming both workers and the environment. The imidazolium family arrived as chemists searched for safer, low-volatility substances with customizable properties. Research on alkyl-substituted imidazolium salts grew as it became clear that longer chains could give surprising properties. The search for functional, versatile, and less hazardous compounds pushed researchers toward 1-vinyl-3-tetradecylimidazolium bromide. The moment vinyl-functionalized systems appeared in journals, interest skyrocketed, since crosslinking in polymer matrices no longer seemed out of reach.

Product Overview

1-Vinyl-3-tetradecylimidazolium bromide bursts onto the scene as a surfactant and ionic liquid, with a strong ability for phase transfer and stabilization within colloidal systems. The long tetradecyl tail, attached to the imidazolium core, shifts the cation’s properties away from the more common short-chain variants. Its unique vinyl group sets it apart from older imidazolium salts, bringing crosslinkable or polymerizable functionality into the world of ionic liquids. This compound fits right in with next-generation anti-static coatings, specialty lubricants, advanced electrolytes, and engineered emulsifiers.

Physical & Chemical Properties

On the bench, this salt shows as a white to pale yellow powder or viscous oily material, thanks to its high molecular weight and long alkyl chain. 1-Vinyl-3-tetradecylimidazolium bromide dissolves well in polar organic solvents like methanol and DMSO, while splitting water solubility depending on chain conformation and temperature. The melting point often falls between 40 to 60°C, depending on hydration or impurities. This ionic liquid resists decomposition under moderate heating, but old-fashioned strong acids or bases break it apart. Electric conductivity drops compared to shorter alkyl derivatives, yet the surfactant properties spike, especially in microemulsion systems.

Technical Specifications & Labeling

Quality manufacturers list the compound’s purity at or above 98%, monitoring residual solvents and any color changes with each batch. Labels always display the molecular formula C25H45BrN2, clear storage temperature guidelines, hazard pictograms, and emergency handling advice. The typical batch lot number, CAS number, and shelf life information make the supply chain easier for both labs and industrial customers. Attention runs high regarding moisture control, since water can shift its physical behavior or interfere with downstream chemical processes.

Preparation Method

Synthesis generally starts with N-alkylation of N-vinylimidazole, using tetradecyl bromide in dry acetonitrile or a similar solvent. The reaction proceeds under an inert atmosphere, protecting the sensitive vinyl group from side reactions. One-pot approaches see temperature adjusted to drive the reaction forward without frying the vinyl functional group. Afterward, repeated washing and crystallization, often with ethyl acetate or diethyl ether, remove unreacted precursors, leaving behind the product as a relatively pure solid. Companies constantly tweak process variables: they try different alkylation catalysts or switch purification solvents to boost both environmental safety and yield.

Chemical Reactions & Modifications

This salt’s vinyl group unlocks post-synthesis chemistry rarely found in the ionic liquid world. Free radical polymerization brings the cation directly into polymer backbones, dramatically altering material flexibility, solubility, and ionic conductivity. Grafting reactions yield functional surfaces for selective separation technology. In my own projects, this compound survives transesterification, Michael additions, and mild oxidations. Even small tweaks to its structure—say, swapping halide anions, or lengthening the alkyl chain—can change how it assembles on surfaces or how it scatters light. Researchers continue to test new chemical modifications, pushing the boundaries of ionic liquid design for next-level performance.

Synonyms & Product Names

Scientists and tech specialists know 1-vinyl-3-tetradecylimidazolium bromide under several banners. Common names include 1-vinyl-3-n-tetradecylimidazolium bromide, [VC14Im]Br, and N-vinyl-N’-tetradecylimidazolium bromide. Industrial suppliers stick to names like VTI Bromide or simply list the systematic name for clarity. No matter which name appears on packaging, it draws the same attention in research circles.

Safety & Operational Standards

Care in handling stands out as the main rule in labs and factories. Based on both the bromide anion and the vinyl-imidazolium backbone, contact with skin and eyes triggers significant irritation. Respirable dust causes discomfort, and accidental swallowing raises toxicity concerns. Labs installing local exhaust ventilation and always specifying eye protection make a difference for worker safety. Spills require prompt cleanup with absorbent pads and strong ventilation, never a casual broom. Proper waste storage, double-sealed and marked as hazardous, helps prevent environmental release. Material safety data sheets from reputable manufacturers back precise guidelines for storage, handling, and transport.

Application Area

Engineers and chemists reach for this salt to tackle complicated emulsions, tough phase separation challenges, and hard-to-stabilize electronic interfaces. In electrochemistry, this ionic liquid gives batteries, fuel cells, and supercapacitors a reliable choice for non-volatile, high conductivity electrolytes. Its surfactant skills show up in nanoemulsion stabilization, especially during nanoparticle synthesis. Coatings companies explore the vinyl group’s bond-forming powers, testing anti-static and anti-fouling surfaces for electronic housings and medical equipment. Polymer scientists find new directions for crosslinked gels and membranes with tailored permeability and mechanical strength. Research journals fill up with papers showing this compound’s impact in sensor design, drug delivery systems, and water purification processes.

Research & Development

University groups and commercial labs keep building fresh polymerization techniques to exploit the vinyl moiety, aiming for light, tough, or conductive materials impossible with legacy solvents or salts. Companies invest in high-throughput screening to sort out which structure tweaks give optimal performance for fuel processing or advanced separations. Every year, findings reveal yet another trick involving charge transport, responsiveness to temperature, or interfacial tension. Researchers noting slow biological degradation rates keep troubleshooting safe disposal or recycling schemes, recognizing the need to keep such powerful chemicals from persisting in water or soil.

Toxicity Research

Lab animal studies and cell assays tell a story of high potency: sub-millimolar concentrations already disturb membrane structures and protein folding. Dermal and ocular testing support the call for strict personal protection in the workplace. Bromide anions carry their own toxicological risk, interfering with central nervous system function after cumulative exposure. Comprehensive environmental impact research grows in importance each year. Regulators keep a close eye on waste streams from industrial use, requiring meticulous record-keeping and risk assessments for new products introduced to the consumer market. To move forward responsibly, the chemical industry supports wider studies on breakdown products and bioaccumulation trends.

Future Prospects

This compound’s potential has hardly begun to play out, as labs move beyond simple solvents or electrolytes into nano-enabled devices and smart polymer matrices. The world of energy storage looks especially eager for ionic liquids that hold up under long cycling while resisting dendrite formation. Demand for flexible electronics and medical devices with sterilizable, anti-bacterial coatings keeps pushing innovation in crosslinkable ionic compounds. Circular economy principles motivate chemists to redesign not just for function but also for recovery and reuse, reducing hazardous waste and closing the loop. Startups and blue-chip suppliers look to licensing deals and patents, determined to shape the next generation of specialty materials built around functionalized imidazolium salts. Every new discovery brings chemical workers, public safety officials, and environmental scientists into urgent conversations about how to balance performance with stewardship.

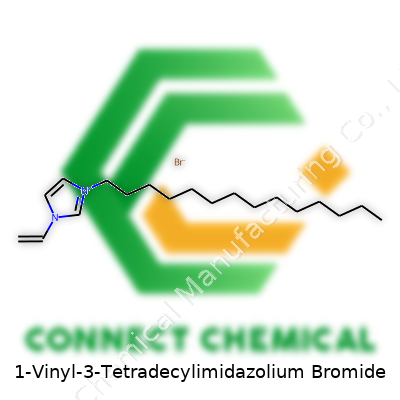

Unlocking the Structure

Getting to the heart of 1-vinyl-3-tetradecylimidazolium bromide means picturing a molecule in three parts. At its core, you find an imidazolium ring—a five-membered aromatic ring with two nitrogen atoms sitting at positions one and three. This backbone forms the stable center for a variety of ionic liquids. Two important groups branch from this ring: a vinyl spacer at the first nitrogen, giving it a reactive double bond, and a tetradecyl chain at the third, stretching 14 carbons like a tail. The overall structure forms a cation because the imidazolium ring holds a permanent positive charge. Tagging along is a single bromide anion, balancing out the charge but not binding directly to the core.

In plain terms, that’s a vinyl group on one side, a long-fat carbon chain on the other, and the aromatic core in the middle. Each of these parts brings something unique, and that’s why this compound keeps showing up in labs around the world.

Why This Structure Has Scientists Talking

Every piece of the molecule has a job. The long tetradecyl chain brings serious hydrophobic character, letting this compound interact and sometimes mix with oily, nonpolar substances. That’s important in fields like solvent extraction, where chemists separate out stubborn compounds that don’t play well with water. The imidazolium ring does more than just hold things together—it creates a pathway for ionic conduction and chemical stability, which you don’t often find together in organic chemistry. Slap a vinyl group on that nitrogen, and now you’ve got a reactive site ready for polymerization or grafting onto surfaces.

Studies from recent years (like the review by Zhang et al., 2022, in Chemical Reviews) highlight how the combination of the ring and the long chain opens doors in green chemistry. Imidazolium ionic liquids show low volatility, resist fire, and often replace more toxic chemicals in industrial processing. Their structure tunes everything: change the chain length, swap a vinyl group, and suddenly you get a liquid with a whole new set of skills.

Where the Challenges Lie

No chemical gets a free ride. One trouble spot: manufacturing these ionic liquids still uses significant energy and often hazardous reagents. Bromide, while handy for balancing charge, doesn’t always behave in environmentally friendly ways. Ongoing research tries switching it for more benign anions or recycling strategies to keep things sustainable.

Another issue comes up with the long tetradecyl group. It makes the compound more persistent in ecosystems, and scientists are only beginning to track the consequences of more widespread use. The Centers for Disease Control and similar agencies remind us: compounds that end up in waterways can have subtle but far-reaching impacts.

Ways Forward

Researchers deserve credit for pushing new synthesis routes that use renewable materials and create less hazardous waste. One example from Green Chemistry Journal (Wang et al., 2021) shows how enzymes, instead of harsh acids, build imidazolium structures with less environmental fallout. Redesigning the anion and tweaking the side chain have also led to less bioaccumulative and more rapidly degradable alternatives.

Transparency matters too. Sharing toxicology data and lifecycle analysis helps both chemists and policymakers make choices that leave a lighter footprint. Sometimes that means taking a step back from technical performance and asking, “How does this molecule interact with the world outside the test tube?”

The chemical structure of 1-vinyl-3-tetradecylimidazolium bromide isn’t just a diagram on a whiteboard—it’s the key to understanding its successes and its risks. Real progress comes not just from discovering new molecules, but from building them in ways that respect both science and society.

Why This Specialty Chemical Matters

From my years trading input with laboratory pros and research chemists, I’ve noticed certain ionic liquids pop up every time the conversation turns to advanced materials or electrochemistry. 1-Vinyl-3-Tetradecylimidazolium Bromide isn’t a household name, but engineers and scientists have a good reason to keep coming back to it. Its chemical structure, part imidazolium backbone, part long-chain alkyl tail, helps it work where more familiar solvents or surfactants let them down.

Stabilizing Nanoparticles for Research and Industry

Making nanoparticles and preventing them from sticking together is tricky. Many research groups reach for this ionic liquid to keep metal nanoparticles from lumping up. Imidazolium-based chemicals form a kind of shell around those tiny particles, stopping them from clumping. Gold and silver nanoparticles, for instance, respond to its stabilizing power. This opens the door to sensors, catalysts, or advanced coatings without the usual headaches of aggregation. It’s not just theory: the literature backs up higher yields and more reliable particle sizes.

A Secret Weapon in Electrochemistry

Electrochemical cells can demand materials that stay stable through heat, electrical current, or tricky chemical reactions. This substance finds a place in studies on lithium-ion batteries, dye-sensitized solar cells, and supercapacitors. One reason? The compound resists losing its structure during charging cycles or when exposed to voltage swings, which comes up again and again in journal articles. Its ionic nature also bumps up ionic conductivity, which keeps the current flowing smoothly and can help push for higher battery capacities or better charge rates.

Helping Polymer Chemists Build Smart Materials

Synthetic chemists turn to 1-Vinyl-3-Tetradecylimidazolium Bromide when they’re after specialty polymers. They use it as a monomer or as a functional additive during polymerization. With it, they've built membranes that filter ions for water desalination or fuel cell projects. Its long alkyl chain brings unexpected flexibility and lower permeability for unwanted contaminants, often a weak point in earlier designs. More recently, groups have published results on anti-fouling and antimicrobial coatings, tapping into the inherent anti-microbial properties of the imidazolium group.

An Emerging Choice in Green Chemistry

Solvent choice shapes lab safety and environmental impact. Many legacy organic solvents come with serious drawbacks: volatility, flammability, toxicity. Ionic liquids such as this one can replace traditional options in synthesis setups. They don’t readily evaporate; they present far lower fire hazards, and the research community acknowledges reduced emissions as a big plus. Teams focused on sustainable process design flag this liquid as a route for recycling or extracting metals from waste, because recovery and reuse comes easier than with older solvents.

Looking to the Future

For now, this ionic liquid looks like a specialty tool—something for niche applications or highly controlled processes. With new regulations around waste, fire safety, and chemical exposure, I’ve seen labs switch over from familiar but hazardous solvents to ionic liquids in surprising ways. If researchers keep showing value across electrochemistry, materials science, and green engineering, 1-Vinyl-3-Tetradecylimidazolium Bromide could shift from “advanced research chemical” to a staple in production-scale projects.

Knowing Your Ionic Liquids

Solubility often shapes the real-world value of a chemical. That’s hard to ignore with 1-vinyl-3-tetradecylimidazolium bromide. I’ve come across this ionic liquid in the lab and the way it prefers some solvents over others makes a big difference for researchers and some niche industrial uses.

The Structure Speaks Volumes

So why do chemists pay attention to its long alkyl chain? The tetradecyl tail brings a hydrophobic nature to the molecule, and the imidazolium head brings the charge. The 1-vinyl group sometimes brings reactivity people want, but for most, it's the solubility question that matters first.

What Happens in Water?

Taking this ionic liquid to water, don’t expect much. Its bromide part is happy in polar, hydrophilic surroundings, but the rest of the molecule holds back. That long tetradecyl chain doesn’t mix well with water. In experience, as well as in studies, it stays stubbornly out of solution beyond low concentrations. Maybe a small cloudiness forms, maybe a thin film at the top. People interested in ionic conductors, extraction processes, or even antimicrobial coatings run into this roadblock.

Moving to Organic Solvents

Things get easier with organic solvents. Solvents like chloroform, toluene, or dichloromethane pair up well with the long hydrocarbon chain. This dissolves the entire molecule so much more effectively, removing the separation headaches seen with water. At the bench, I found simple mixing gives a clear solution in these organic media, no heating or sonication needed. Alcohols like methanol and ethanol do a bit better than water, but the lower polarity means the chain can spread out more and the ionic head is tolerated.

Solubility Determines the Application

Where does this matter? Beyond the simple curiosity, picking the right solvent sets the success or failure of a reaction or a formulation. For polymer chemistry, the tendency to dissolve in organic phases brings better results when creating ion gels or processable films. Surface-active uses, like dispersing in oil phases or preparing nanoparticle suspensions, get much easier when the solvent isn’t fighting the molecule. Trying to use it in water-based setups often means surfactants, co-solvents, or emulsifiers just to maintain an acceptable dispersion.

Supporting Data and Observations

Researchers measured the solubility across solvents and saw swollen values in toluene, chloroform, and cyclohexane, while water and brines showed almost nothing at typical lab temperatures. The drop in solubility in water is commonly connected to the long alkyl chain increasing hydrophobicity, shifting the balance out of the polar realm. In peer-reviewed works, only millimolar amounts go into water, and evaporation usually brings the liquid out again.

Thinking About Solutions

So what to do if water solubility is really needed? Some teams tinker with shorter alkyl chains or add ethylene oxide units to boost water affinity, but that changes performance in the original application. Blending with surfactants or preparing as part of microemulsions can help for some cases, at the cost of added complexity and sometimes unwanted side reactions. Checking the solvent compatibility at the start of a project often saves both money and time down the line.

Wrapping Up

Anyone working with 1-vinyl-3-tetradecylimidazolium bromide ends up tailoring solvents to the job. Experience and the published literature both point to organic solvents for easy dissolving, and water mostly stays out of the picture without heavy modification. Recognizing this up front simplifies planning and sets research on a smoother path.

Respecting Chemical Hazards in Real Life

Anyone who’s spent time in a lab knows things get risky as soon as you start handling specialty chemicals, especially when the names get this long. Take 1-vinyl-3-tetradecylimidazolium bromide—an ionic liquid catching the eye of lots of researchers these days.

This stuff brings some neat properties for advanced applications, but it doesn’t come without risks. The science behind it tells you as much: we’re dealing with a compound that has both organic and ionic features, which means nobody really wants it all over their skin or in the air. In places I’ve worked, the best chemists keep a bottle of soap handy, but they also take chemical hygiene dead seriously. There’s a reason.

Treating Every Reagent Like It Bites

Look at the material safety data sheets. Even if a sheet says “low acute toxicity,” you treat it with respect because the long-term health data just isn’t there yet. With similar imidazolium-based chemicals, skin and eye irritation pop up plenty often in the research record. The longer alkyl chain on the tetradecyl group can boost hydrophobicity, making spills harder to clean up, and if you drop a bottle, you’d better not rely on paper towels. From my own time handling ionic liquids, gloves and a fume hood never felt optional, but essential.

Daily Laboratory Practices

Gloves should fit well and get changed when contaminated. Nitrile types are good for most organic liquids, and lab coats shield against splashes. I learned to keep safety goggles over my eyes, no matter how trivial the task seemed. If there’s any chance of a reaction or someone else using volatile chemicals nearby, a face shield adds another layer of protection. Standard fume hoods need regular air flow checks; you can’t always smell danger with low-volatility compounds like these.

When measuring, never use the bare hand to grab containers. If powder or droplets stick to a glove, take that glove off before you touch anything else in the room. Spill control kits stand by for a reason—the cleaner the workspace, the lower the odds of something turning into a big problem.

Disposal and Environmental Responsibility

We share responsibility for where our chemicals end up. Ionic liquids sound greener because of their low vapor pressures, but that can fool people into being careless with waste streams. Waste from these sorts of materials needs collection in labeled containers—never down the sink. My own experience working with environmental services reminded me that local waste rules often set stricter standards for emerging chemicals, since water-treatment plants can’t break down exotic compounds.

Emergency plans also matter. Labels need to be clear and up-to-date. Exits and eye wash stations should never be blocked. It's not just about ticking off a checklist but respecting the safety culture that keeps everyone in a lab heading home at night.

Staying Informed and Adaptable

The chemistry world changes fast, and so should our knowledge. New reports on ionic liquid toxicity turn up every year. People with boots-on-the-ground experience notice trends and raise alarms about common issues long before they become official policy. That’s why talking with colleagues matters just as much as reading up on academic literature.

Real safety never comes from a single rulebook. What works today might need an update tomorrow. A hands-on, team-based approach builds habits that keep risk where it belongs—in theory, not in the workplace.

Understanding Purity for Lab and Industry

Working with ionic liquids like 1-Vinyl-3-Tetradecylimidazolium Bromide brings a whole set of expectations, especially in purity. Synthetic chemists and process engineers count on batches hitting purity levels upwards of 97%. At this mark, side reactions and impurities sit low enough that researchers stay confident about results, especially when using the compound in catalysis or for novel polymer materials. Purity around 99% boosts trust for anybody preparing functional materials or running sensitive organic syntheses.

Research communities and chemical suppliers often share certificates of analysis. These spell out water content, residual solvents, and trace metals. Water often gives ionic liquids a hard time, changing solubility or even physical appearance. Even a few tenths of a percent can throw off precision applications. Impurities like halides or leftover organics introduce headaches for folks chasing repeatable electrical properties or targeting pharmaceutical standards.

From my own bench time, low-purity samples slow progress more than people expect. If a compound takes days to synthesize and purification steps drag, teams eat into budgets and patience. Some researchers try recrystallization or column chromatography to improve a low-grade commercial sample, but not every ionic liquid offers an easy fix. Choosing suppliers who consistently deliver near-anhydrous, high-purity material keeps projects on time and results reliable.

Storage Keeps Quality and Safety Intact

Once high-purity 1-Vinyl-3-Tetradecylimidazolium Bromide lands in the lab, storing it right becomes the quiet foundation of success. Keeping the container tightly sealed matters a lot. Air moisture creeps in, and bromide salts love to attract water — soon, crystals turn sticky or clumpy. In some batches, haze or even droplets inside the vial signal something’s slipping. Stashing bottles in a desiccator or with plenty of drying agent helps. The best practice is keeping it out of light too, because light can kick off small decomposition processes, especially with the vinyl group.

Room temperature won’t ruin the salt, but colder locations like a refrigerator mean more stability if months of storage are expected. I’ve seen samples last well over a year in dry, dark cabinets, but every freeze-thaw cycle offers a chance for moisture to sneak back in. Sharing fridge space with other chemicals takes planning, and no one wants their ionic liquid absorbing odors from aldehydes or amines.

Donning gloves counts for more than just personal safety: ionic liquids, especially imidazolium varieties, stain skin easily and hold onto fingerprints. Uncapped bottles near lab sinks or reagent shelves collect dust and contamination. Taking a minute for clean scoops and tight lids makes a difference over the lifespan of even a small bottle.

Solutions for Everyday Labs

Some teams skip headaches by buying small quantities and running quality checks on arrival: simple Karl Fischer titrations for water, NMR for purity, and regular TLC for decomposition. Labels tracking open dates give everyone a sense of shelf time. In larger settings, setting up shared storage guidelines prevents surprises, ensuring that every researcher pulls from a bottle with the same reliable punch.

Synthetic labs working in new directions should reach out and check technical support from vendors. Often, suppliers back purity with batch-specific data, and asking for help isn’t just for big clients. Feedback from real-world use cycles into the next production run, and collective care pays off for anyone who values both solid safety standards and experimental success.