Benzyldimethylstearylammonium Chloride Monohydrate: Beyond the Basics

Historical Development

The story of benzyldimethylstearylammonium chloride monohydrate weaves through more than a century of chemistry, echoing the rise of quaternary ammonium compounds after World War I. Early chemical engineers looked for ways to fight microbial contamination in both hospitals and food production. Research in the 1930s and 1940s gave birth to the so-called “quats,” compounds built for antiseptic and cleaning purposes. Among these was benzyldimethylstearylammonium chloride monohydrate. By the 1950s, this compound stood on pharmacy and hospital supply shelves in the form of aqueous solutions and powders. Chemists saw its hydrophobic tail and charged nitrogen head as a clever answer to the era’s infection control problems. Demand spiked, and the path toward bulk industrial use began.

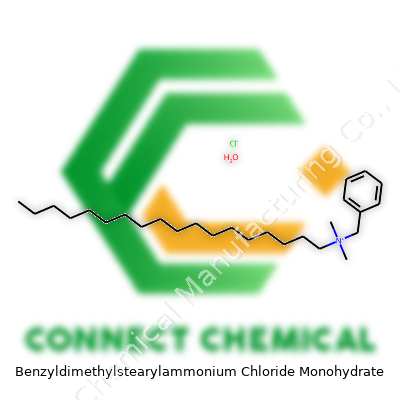

Product Overview

Benzyldimethylstearylammonium chloride monohydrate, often called BDSAC, falls into the class of surfactants known for their strong antimicrobial and antistatic properties. It carries a long hydrocarbon chain attached to a nitrogen core, balanced by a chloride ion and a molecule of water. This structure means BDSAC acts as more than just a cleaner. It brings together the oil-pulling power of surfactants and the germ-killing punch needed in crowded public spaces and medical facilities. Everyday folks rarely think about the chemical names behind disinfecting wipes or water treatment tablets, but this compound helps keep both environments safer for everyone.

Physical and Chemical Properties

BDSAC commonly takes form as a white or off-white powder, sometimes as flakes. It dissolves easily in water and ethanol, with a mild soapy scent. The compound’s quaternary ammonium skeleton allows for strong attraction to surfaces. This stickiness helps form an invisible barrier that repels dirt, oil, and most bacteria. It melts at relatively low temperatures—usually under 70°C—and resists degradation under standard warehouse conditions. Chemically, the positive charge on its nitrogen center binds to the negative ends of cell membranes in microorganisms, causing them to rupture. This has made BDSAC a staple in rooms demanding sterile surfaces.

Technical Specifications & Labeling

Suppliers typically detail purity levels above 98%, along with moisture content, pH in solution, and melting points. Packaging must keep out light and moisture to guard the compound’s stability. Labeling standards have grown tougher, fueled by both regulatory shifts and customer complaints about allergic reactions and improper use. As someone concerned with safe workspaces, I know that clear concentration instructions and visible hazard warnings go a long way to prevent accidental skin contact or respiratory irritation. Material safety data sheets shouldn’t hide critical details. Ensuring workers and users understand what is inside each container remains a priority, especially in industries where chemical exposure happens every day.

Preparation Method

Chemical production starts with a reaction between stearyl dimethyl amine and benzyl chloride, run in aqueous or alcoholic media. Manufacturers control temperature to reduce side reactions. The process handles hazardous reagents, so reliable ventilation, well-trained staff, and automated dosing rigs reduce spills and worker injuries. Once the main reaction finishes, purification steps, such as recrystallization in a polar solvent, extract the monohydrate form, which scientists have shown to offer better shelf stability than its anhydrous cousin. Quality control samples from every batch run through chromatography and titration to keep heavy metals and byproducts in check.

Chemical Reactions and Modifications

BDSAC’s big hydrocarbon tail can withstand moderate acids and bases but breaks down under strong oxidizing conditions. Chemists have experimented with replacing the stearyl group for other fatty chains, tuning the surfactant’s solubility and effectiveness against particular pathogens. Alkylation and quaternization reactions form the product’s core, keeping the nitrogen atom’s full positive charge intact. The benzyl group offers some flexibility, acting not just as a scaffold, but also in modulating affinity for different cell membranes. In the laboratory, modifications tweak charge density, aiming either for stronger bacteriacidal action or milder, skin-safe versions for personal care.

Synonyms and Product Names

Across the globe, BDSAC appears under a raft of names—Stearyl dimethyl benzyl ammonium chloride, Stearylbenzyl dimethyl ammonium chloride hydrate, and so on. Pharmaceutical and cleaning product companies spin their own brand names, hoping to mask the chemical’s tongue-twisting title. This proliferation sometimes sows confusion, especially in procurement offices and regulatory agencies where synonyms can lead to mix-ups. For me, reliable cross-referencing in chemical inventories keeps mishaps at bay and helps meet both local and international compliance rules.

Safety and Operational Standards

Safety procedures remain a frontline concern wherever workers handle BDSAC. The compound can cause skin and eye irritation on contact, and accidental inhalation sparks coughing and congestion. Engineering controls like fume hoods, splash guards, and PPE—including gloves, goggles, and face masks—offer frontline defense. I’ve seen poor safety habits escalate into long-term health complaints in production workers, so safety data sheets and emergency instructions need to be simple, clear, and updated regularly. OSHA and similar agencies worldwide set maximum allowable limits, but it falls to each facility manager to ingrain good habits and routine refresher training. Wastewater management grows increasingly important, since releasing quats into the environment has raised concerns about aquatic toxicity and bioaccumulation. Calls for stricter discharge requirements and greener alternatives have only grown louder.

Application Area

BDSAC enjoys a broad reach in disinfectant wipes, floor cleaners, textile antistatic sprays, leather treatment solutions, and water purification tablets. The food processing sector leans on it for sanitizing surfaces between production runs. Hospitals and public transportation agencies rely on its quick-acting germicidal power to control disease outbreaks. Away from human contact, it steps up in oilfields as a biocide in drilling fluids and pipelines. Industrial laundries benefit from its power to prevent static buildup, which helps avoid dust and debris settling on fresh fabrics. Regulatory shifts and consumer pressure in recent years have swayed some vendors toward less persistent disinfectants, but BDSAC remains a first-line agent in many high-risk, high-traffic zones.

Research and Development

Research teams continue refining quaternary ammonium compounds looking for new blends that balance antimicrobial punch with milder toxicological profiles. I’ve seen university labs test BDSAC against multi-drug-resistant bacteria, searching for formulations that blunt the odds of pathogen adaptation. Advances in synthetic pathways have brought down production costs and boosted consistency between batches. By adjusting the length and branching of the hydrophobic tail, scientists can target specific bacteria or tweak performance in hard water. R&D groups watch for the next regulatory curveball, always weighing which modifications meet new environmental or safety standards without losing performance.

Toxicity Research

BDSAC’s toxicity profile shadows that of similar quats. Acute exposures can irritate skin and mucous membranes, while high-dose ingestion risks gastrointestinal upset, vomiting, or worse. Chronic exposure studies in animals point to mild liver or kidney changes at sustained high doses, but most toxicity reviews show limited absorption through intact skin. BDSAC residues in water streams, though, remain contentious. Environmental scientists cite evidence of toxicity to some aquatic species, especially invertebrates and algae. They raise flags about quats encouraging toughened biofilm strains in hospital drains and wastewater. International regulators have started capping discharge levels, but gaps in long-term health studies keep the conversation alive. Stronger data transparency and standardized test protocols seem overdue.

Future Prospects

The market outlook for BDSAC responds to three tracks: tightening health regulations, demand for greener disinfectants, and the rise of antibiotic-resistant pathogens. Chemical firms work on “degradable quats” that fade fast after application, aiming to soothe regulators’ worries about environmental persistence. I hear more buyers asking for information on biodegradable profiles, allergenicity, and combined product claims. Hospital procurement boards have looked for alternatives, but the proven track record of BDSAC in infection control remains hard to match. Future product development may draw from biotechnology, with peptide-mimicking quats or microencapsulation promising smarter, targeted action. The industry needs to step up communication with consumers, supporting risk-balanced regulations and pushing companies toward transparency, proving to communities that powerful disinfectants can fit both high safety standards and environmental responsibility.

Why This Chemical Shows Up in So Many Places

Walk through any hospital or nursing home, and strong cleaning solutions fill the air. Disinfectants matter here. Benzyldimethylstearylammonium chloride monohydrate, a long name with a focused purpose, gets mixed into many of those products. This compound’s track record in killing bacteria and some viruses makes it a staple in surface sprays, wet wipes, and sometimes industrial sanitizers. At home, people might not realize it hides behind generic labels on bathroom or kitchen cleaners.

Quaternary ammonium compounds—quats for short—like this one do more than scrub away dirt. They push back against germs left behind on counters, medical instruments, or even in swimming pool water. I’ve handled plenty of daycare messes, and reading the label shows the power of these ingredients to keep a classroom safer during flu season. In healthcare, they bring peace of mind by lowering the risk of spreading bugs like staph or E. coli.

Beyond Disinfection: Other Roles in Daily Life

This chemical doesn’t stop at killing microbes. Textile makers count on it too. Think soft bed sheets in hotels and uniforms that resist microbes—manufacturers treat them with just such compounds. Food workers also value equipment that stays cleaner for longer. I’ve seen its name in ingredient lists on hard-surface cleaners for restaurants.

Personal care products carry their own risks and rewards. Some makers add trace amounts to shampoos or conditioners. The aim is to reduce static or provide a smoother feel. My own stubborn winter hair can confirm how well these surfactants flatten the frizz. Still, most personal hygiene products make only minimal use of this chemical because high concentrations would irritate the skin. Companies usually steer clear of putting strong disinfecting substances in products meant for direct skin contact.

The Ongoing Debate and Health Considerations

No discussion would be honest without addressing the flip side. Concerns about overexposure come up, especially in hospitals. Prolonged skin contact sometimes causes irritation or allergic reactions. Quat disinfectants, including this one, sometimes trigger headaches or breathing discomfort. This risk jumps up for custodial workers or healthcare staff using sprays several hours a day. I once spoke with a janitor who switched hand soaps after a stubborn case of dermatitis, traced back to constant contact with cleaning agents containing this group of chemicals.

Questions about resistance are growing louder. Pathogens adapt, and there’s suspicion that heavy reliance on harsh disinfectants nudges bacteria into new territory, growing tougher against standard cleaning agents. This is a worry that hides beneath the surface, but research out of universities in both North America and Europe shows bacteria in labs developing adaptation traits with frequent exposure.

Smarter Ways Forward

Anyone who relies on these products can take steps to balance cleanliness and safety. Gloves offer easy protection for hands. Good ventilation helps cut down on inhaling vapors. Switching between different active ingredients—rather than cleaning only with one—keeps bugs guessing and might slow resistance.

Clear labeling helps too. People want to know what chemicals linger in their homes or workplaces. Companies can step up with better warnings and instructions for those using cleaning agents all day. Schools can provide education about safer handling.

Benzyldimethylstearylammonium chloride monohydrate works well where real disinfection is critical, but the story doesn’t end with a clean surface. Appreciating both its power and its trade-offs creates smarter choices for everyone involved in keeping places safe.

Why Care about Safety?

The name might sound like it’s straight out of a chemistry exam, but benzyldimethylstearylammonium chloride monohydrate pops up in hospitals, cleaning products, and plenty of labs. It’s a substance with teeth: strong as a disinfectant and a real risk if you don’t show respect. I’ve worked in labs where folks nearly learned about toxic compounds the hard way. Years of experience taught me that treating every bottle like it could bite saves health and careers.

Direct Contact Is Serious Business

It won’t wait for mistakes. This salt irritates the skin, eyes, and respiratory system. Touch it, and your hands can tingle and burn. Splash in the eyes—redness, pain, possibly worse if you ignore it. Breathing in dust or mist sends your lungs looking for revenge. Looking at usage reports, I’ve seen how quickly things go south without gear. The standard cotton lab coat and a wimpy pair of gloves don’t cut it.

So what keeps you safest?

- Wear nitrile or neoprene gloves—latex doesn’t do the job.

- Safety goggles protect your vision; a faceshield is better for bigger spills.

- A long-sleeved chemical apron blocks splash surprises.

- Pull on a quality vapor mask if you’re using it in bulk or anything fume-heavy.

Ventilation Isn’t Just a Box to Tick

No point in gearing up if vapor hangs in the air. Working in open rooms with a proper fume hood cuts down your risk right away. I’ve seen overzealous bleach and these ammonium compounds set off headaches for an entire crew—all because they ran only a tiny vent fan. Don’t trust cracked windows or old air systems. If you smell anything, it’s probably too late: get out, air the place, and fix your process.

Storage Matters Just as Much

Stuffing bottles under the sink isn’t good enough. This chemical reacts with strong oxidizers and acids. Mix-ups cause fires and toxic byproducts—no one wants that emergency. I keep mine sealed tight, upright, with clear labels in a cabinet dedicated to chemicals like it. Away from heat, away from sunlight. I check caps for cracks before putting them back. I’ve found damaged containers just from careless handling; those leaks show up quickly and rarely quietly.

Spills: Fast and Focused Fixes

Spills need fast action—delay means health issues or property damage. For small accidents, absorbent pads and neutral cleaners work. For anything bigger, leave the room and suit up before returning. Absorb, clean, rinse, dry. Warn coworkers before restarting business as usual. Any contaminated gear gets sealed and marked for hazardous disposal. I keep spill kits checked and nearby because in real labs, trouble doesn’t send invitations ahead of time.

Training and Emergency Prep

Chemicals don’t care if you’re new or a veteran. Hands-on training sticks better than manuals. Know where the eyewash is, memorize the path to the safety shower, rehearse the emergency phone list. In my team, reflexes matter—we run drills until it feels normal. Stories from hospitals make it clear: hesitation leads to real injuries.

Staying Ahead

Regulations like OSHA and REACH supply clear guidance. Reading those isn’t a one-off. They change as we learn what works and what doesn’t. I keep up by reading updates and talking with safety reps. It saves time, money, and health every year. Nothing beats walking away from your shift in the same shape you started, with no nasty surprises hiding in your bloodstream.

What Matters in Chemical Storage

A lot of people overlook the basics of handling specialty chemicals. Benzyldimethylstearylammonium chloride monohydrate works as a widely used disinfectant and surfactant, but treating it like table salt leads to trouble. I’ve seen what happens when storage gets sloppy—containers cake up or give off odd smells, which means money and time wasted, and workers at risk.

Why Moisture Throws a Wrench in the Works

Any compound with “monohydrate” in its name interacts with water easily. The product’s powdery texture absorbs humidity like a sponge. I remember a facility facing big problems one muggy summer. Their open storage shelves collected condensation, practically inviting clumps to form. Material stopped pouring, and cleaning the mess took days. In most labs and factories, keeping a dry storage space makes all the difference. Dehumidifiers bring the humidity below 50%. Sealed containers—preferably with tight screw caps—keep out moisture from the start. Even a sturdy desiccator cabinet suits smaller amounts.

Heat and Sunlight: Hidden Enemies

Chemicals and heat rarely go hand in hand. Heavy exposure warps the texture, and breakdown can creep in slowly. Once, I found a batch stored near an east-facing window: sunlight all morning, baking the bottles into hardened rocks. Workers had to throw out the whole lot. A steady, cool room—below 25°C—delivers better results. Fluctuating temperatures only increase the odds of clumps and chemical instability. Stick to shaded shelves, away from any hot pipes or equipment.

Choosing the Right Containers

Some plastics break down from long-term contact with chemicals like this one, so skip thin bags or flimsy bins. High-density polyethylene jars do the trick, and solid glass works for many labs I’ve worked in. Both resist chemical reaction and add a barrier against stray moisture. Skip reusing old bottles with faded labels. Chemical confusion might cause hazards or bad reactions. Clean, properly labeled containers set a clear standard and avoid costly accidents.

Keep Food and Chemistry Far Apart

One lesson no one should have to learn twice: food and chemicals never mix. Years ago, I stumbled across a break room fridge where someone stored chemical samples, and no one felt at ease after. Always keep this chemical out of any area used for eating, drinking, or preparing food. Accidental exposure or cross-contamination can cause severe health problems—even just by mistake.

Fire Safety and Emergency Awareness

Dust from quaternary ammonium compounds can ignite given the right circumstances. Some come packaged with flammable hazard symbols. Keep them away from ignition sources. Set up storage in rooms with clear signage and ready access to personal protective equipment—goggles, gloves, and proper ventilation help a lot. Make sure anyone working nearby knows the basics of chemical safety, and keep materials such as spill kits easy to reach.

Staying Informed and Up to Date

Laws shift and new safety research comes out all the time. I always suggest checking safety data sheets directly from the manufacturer for the latest details. Solid chemical safety practices draw on real experience and reliable guidelines. Consistent habits in handling and storing specialty chemicals build a safer workspace—and save time, money, and peace of mind in the long run.

Understanding Safe and Practical Levels

Benzyldimethylstearylammonium chloride monohydrate usually enters the conversation in cleaning products, industrial formulations, and disinfection. Questions about how much to use deserve careful attention—too little, it can miss the mark; too much, risks grow for users, surfaces, and even regulatory headaches. People like me have grown up seeing industrial chemicals work wonders in homes and factories alike, but success always depends on responsible use.

What the Science and Guidelines Say

In surface disinfection, this compound shows its best side in concentrations between 0.05% and 0.2%. Health agencies and manufacturers back this range because it balances effectiveness against microorganisms with user safety. Go to a data sheet from NIOSH or resources from the European Chemicals Agency—they all press for this range in basic cleaning and disinfectant tasks.

For heavy-duty industrial uses like corrosion control or algicidal work, higher concentrations sometimes make sense—up to 0.4% or a bit more under controlled conditions. These uses usually call for workers to handle chemicals with a healthy dose of respect, wearing gloves and eye protection and watching for skin irritation. There’s little room for cutting corners.

Why Concentration Matters in Real Life

I’ve watched people reach for that bottle of disinfectant in a school bathroom, assuming stronger means better. The truth tells a different story. Overconcentration can eat away at flooring and leave behind sticky residues that trap dirt. Families expecting a clean space may get chemical burns instead. Hospitals and factories set rules for a reason, not just to check boxes, but because lives and livelihoods depend on sticking to the right numbers.

Concentrations on labels matter. If instructions call for a 1:100 dilution, that comes out to about 0.1% if your stock solution starts strong. Anything outside the recommended bracket opens the door to trouble—both for effectiveness and for potential health risks.

People sometimes forget how strong quaternary ammonium compounds can be. Reports of contact dermatitis or eye irritation show up in workplaces that push the dose too high, toss out safety instructions, or ignore routine training. Regulators take note: the European Union only allows specific levels, and in the United States the EPA monitors them too.

Paths to Smarter Use

Manufacturers benefit from transparent labeling, clear usage instructions, and links to data sheets. By giving facility managers access to the facts, cleaning crews waste fewer supplies and avoid unnecessary risks. Workers do better when training involves real scenarios, not just slide decks. A story I recall from a warehouse manager stands out—after a string of rashes, they switched to premixed solutions instead of letting each shift eyeball their own doses. Problems dropped overnight.

Waste management must enter the picture too. High concentrations in runoff hit local water systems. Mandating low-phosphate and biodegradable detergents helps—so does enforcing limits at both the point of use and discharge. In my community, water testing relies on these limits to keep rivers safe for fishing and swimming.

The Big Picture

Dosage and concentration determine safety and performance with chemicals like benzyldimethylstearylammonium chloride monohydrate. Informed choices keep people safe, protect the environment, and stretch resources. Those on the front line deserve the facts, not just rules. Wise use today sets up future generations for cleaner water and healthier spaces.

A Closer Look at Environmental Hazards

Benzyldimethylstearylammonium chloride monohydrate shows up in many cleaning products, disinfectants, and various industrial applications. People often reach for products containing similar compounds at home, trusting claims of improved sanitation or greater cleaning power. But once these compounds go down the drain, the story grows complicated.

Based on chemical structure, this compound falls under quaternary ammonium compounds, or “quats.” Quats make strong surfactants and disinfectants, but their toughness makes them slow to break down in nature. Many studies confirm that quats stick around in rivers, lakes, and soil for long periods, which means they keep interacting with plants, microbes, fish, and insects.

Real Evidence of Harm

Researchers have documented toxic effects on aquatic life. Science journals point to reduced growth and even death in algae, small crustaceans, and some fish exposed to pretty tiny concentrations of these chemicals. What I find worrying: even at levels measured in parts per billion, some organisms start showing stress.

Quats disrupt cell membranes, so the same chemical action that makes them great for killing germs also harms life in rivers and lakes. Scientists have watched populations of sensitive species drop in places where quats collect. Even sewage treatment plants only partially remove them; much of the residue washes straight into the environment.

Persistence Builds Up Risk

With repeated use, benzyldimethylstearylammonium chloride monohydrate doesn’t just disappear. It attaches to particles in water and settles in soil or sediment, hanging around much longer than common organic waste. Over time, that persistence means a steady build-up. Farm runoff, stormwater, and household drains all add to the total load on local waterways.

One real-world example: researchers in Europe measured quats in wastewater and downstream rivers and found levels high enough to hurt beneficial bacteria that break down pollutants naturally. When these bacteria struggle, the broader health of the ecosystem takes a hit. Some conditions look subtle — a shift in which microscopic organisms survive — but all the changes add up.

Weighing Benefits Against Risks

It’s clear that disinfectants and cleaning agents bring public health gains, especially in hospitals and food industries. I use them at home and want to keep my family safe. But choosing products without considering environmental costs creates new problems, sometimes out of sight.

That doesn’t mean banning useful chemicals overnight. It means taking responsibility. Some companies already research alternative compounds that break down faster or don’t threaten aquatic life. The rest of us can help by limiting our use of unnecessary disinfectants, choosing greener cleaning products, and supporting wastewater treatment upgrades. Clear labeling and transparency let shoppers make informed choices.

Many people think that rinsing something away makes it go away. But my own experience living near a stream shows just the opposite — the choices we make at the sink matter far downstream. Regulators, chemical makers, and everyday users all share a role in the health of our water and soil.