Didecyldimethylammonium Bromide: Looking at an Old Chemical with New Eyes

Historical Development

Exploring the history of Didecyldimethylammonium Bromide (DDAB) reminds me of the shifting landscape of industrial chemistry. DDAB traces its roots back to the surge of quaternary ammonium compounds during the twentieth century. Back in the '40s, rising demands for stronger, broad-spectrum disinfectants pushed chemical companies to innovate beyond basic soap and bleach. The quarternaries, with their potent surface-active and antimicrobial properties, quickly became a favorite among hospitals and food processors grappling with infection control. Through the decades, tweaks in chemical structure—longer alkyl chains, better anion compatibility—helped DDAB outpace older cousins like benzalkonium chloride, especially when controlling resistant pathogens.

Product Overview

DDAB comes as a white powder or crystalline substance with a faint amine odor. Most chemical suppliers package it in airtight drums or polyethylene-lined containers to protect against moisture and air, since even short exposure degrades its lifespan. A quick glance at the product information sheet highlights three key selling points—high purity (usually north of 98%), ease of dissolution, and strong antimicrobial action at low concentrations. Workers who have handled this compound know its tendency to cake up if stored in humid conditions, so keeping an eye on the stockroom thermometer isn’t just about comfort, it preserves chemical stability.

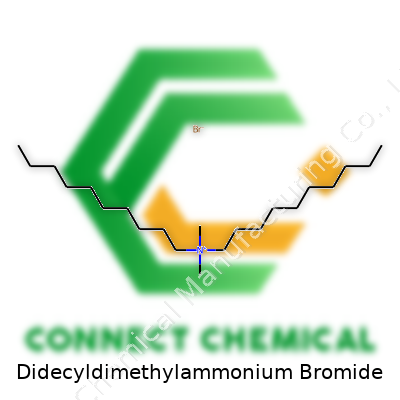

Physical & Chemical Properties

The molecular architecture of DDAB sheds light on its behavior and role in practical applications. With the formula C22H48BrN, DDAB features two decyl (C10) chains, a dimethyl ammonium core, and a bromide counterion. Melting occurs around 80–85°C, and above this point, DDAB flows into a viscous liquid. Since it dissolves well in alcohol and slightly in water, it adapts for sprays, wipes, and concentrated liquid disinfectants. DDAB stands out due to its cationic head, which readily binds to cell membranes, disrupting their function. This makes it lethal to bacteria, viruses, and fungi. Its low volatility also means fewer inhalation hazards compared to lighter quarternaries.

Technical Specifications & Labeling

Accurate labeling ensures everyone from warehouse staff to research chemists stays safe and uses the product correctly. Tech sheets should mark out the chemical name, formula, batch number, lot details, and hazard warnings in a big, clear typeface. Newer regulations demand pictograms for corrosivity and aquatic toxicity. The UN number (UN 3241) matters during transport, flagging the compound for controlled handling. Most DDAB stocks ship in concentrations ranging from technical grade (95–98%) for industrial cleaning to reagent grade (99% and higher) for advanced lab use. For workers, knowing these numbers helps prevent cross-contamination—one mistake with similar-looking containers can compromise entire workflows or put lab techs at real risk.

Preparation Method

The manufacturing process relies on reliable organic synthesis. DDAB production usually starts with dimethylamine, reacted first with decyl bromide to form decyldimethylammonium bromide. Tacking on another decyl chain through the same quaternization route finishes the molecule. Manufacturers optimize every step under controlled temperature and pH to yield pure product and minimize side reactions. Residual solvents and byproducts, if left unchecked, reduce the antimicrobial effects of DDAB, so extensive washing and crystallization often follow. Scale-up from bench to plant scale means constant monitoring—not just for yields, but to avoid runaway reactions or dangerous bromine emissions.

Chemical Reactions & Modifications

One thing you notice in industrial chemistry: even familiar compounds like DDAB never stay static. With new pathogens and regulatory shifts, companies pivot to chemical modifications. By swapping the bromide counterion for chloride, you get a product that may cost less and degrade more safely in the environment. Some manufacturers blend DDAB with other quats to create broad-spectrum disinfectants targeting biofilms or specific spore-formers. Research groups sometimes attach functional groups to the alkyl chains, tweaking hydrophobicity and testing against resistant bacterial strains. What emerges is a living chemical landscape, where yesterday’s solution faces constant challenge and reinvention.

Synonyms & Product Names

The chemical trade relies on a tangle of names. DDAB appears under several synonyms, including Di-n-decyl dimethyl ammonium bromide, DDABr, and decyldimethyldidecylammonium bromide. Catalogs from Sigma-Aldrich, TCI America, and local suppliers often list it under a proprietary label. These variations can confuse buyers hunting for a consistent source. Checking the CAS number (2390-68-3) cuts through ambiguity. In my time searching lab stockrooms, skipping this cross-check has led to some frustrating delays and accidental substitutions on high-stakes projects.

Safety & Operational Standards

Anyone who’s worked near industrial containers of DDAB understands the importance of handling standards. Contact with skin leads to irritation; inhaling its dust creates respiratory hazards. Safety Data Sheets stress gloves, goggles, and local exhaust ventilation. Spills require neutralizing agents to reduce environmental runoff. On bigger scales, plant protocols call for frequent health monitoring for workers, and vapor-phase detection alarms in storage spaces. Regulation has tightened since the early days—now, discharge into public waterways falls under heavy scrutiny, and effluent must meet strict toxicity limits. Not just a matter of regulatory compliance, these steps have proven real-world benefits for workplace health and neighborhood safety.

Application Area

Hospitals, food processing plants, veterinary clinics, and even cruise ships rely on quaternary ammonium compounds like DDAB to limit outbreaks. DDAB brightens up as surface wipes, hand-wash formulations, and room foggers where the goal is to keep pathogens away. During influenza seasons, I've watched custodial teams load up on these compounds, blending them just right for floors, medical gear, and public restrooms. Outside infection control, researchers use DDAB in gene delivery experiments, benefitting from its ability to form lipid bilayers and carry DNA into cells. Water treatment facilities mix DDAB into some pipeline cleaning regimes, taking advantage of its persistent antibacterial action. In the aquatic industry, DDAB takes out parasites and algae in recirculating tank systems.

Research & Development

R&D teams have never stopped tinkering with DDAB, looking for ways to beat resistant microbes and cut down toxicity. Take surface coatings with DDAB-impregnated polymers—newer products keep releasing the disinfectant slowly over time, offering a longer barrier on high-touch surfaces. Scientists lean into structure-activity studies, probing how small shifts to the decyl chains boost performance against hard-to-kill organisms like norovirus and MRSA. With green chemistry protocols, the aim swings toward eco-friendliness, searching for DDAB derivatives that break down faster after use. Collaborative research between academic labs and industry supply chains keeps innovation alive, connecting the tough questions of occupational safety with the practical needs of global sanitation.

Toxicity Research

Scrutiny over quaternary ammonium compounds has sharpened as environmental standards rise. Toxicology studies show that improper releases threaten aquatic life, especially in slow-moving waterways. Fish and invertebrate exposures at moderate concentrations show gill damage and reproductive disruption. On land, people working repeatedly with DDAB sometimes develop contact dermatitis or allergic reactions. Chronic exposure links up with bronchial irritation and, in rare cases, more serious lung damage. Regulatory boards require comprehensive animal and cell-line studies before approving new applications, and manufacturers must run fate-and-transport models to predict environmental buildup. The call for responsible stewardship rings louder year on year, not only for regulatory purposes but out of shared responsibility to those downstream or downwind.

Future Prospects

Looking out toward the next decade, DDAB faces a crossroads. Demand for cleaner hospitals and safer food plants keeps its stock high, but skepticism over persistent chemicals drives both research and regulation. The industry leans into developing biodegradable alternatives, formulating “greener” blends that punch down pathogens without polluting water or soil. Advances in nano-encapsulation may allow controlled release, minimizing exposures and improving safety for workers. Machine learning and computational chemistry start mapping out how to tweak the molecule for maximum performance with minimum harm. I expect stricter labeling and lower permissible limits—changes that push for innovation but also for careful, thoughtful use. The story of DDAB, rooted in old chemistry and modern challenges, echoes questions every industry faces: how to balance efficacy, safety, and the long-term health of people and planet.

What Didecyldimethylammonium Bromide Actually Does

Take a look under the kitchen sink or that broom closet in the hospital, and there’s a good chance you’ll spot cleaning products promising to kill germs. Didecyldimethylammonium bromide is an ingredient that turns up in many of those bottles. It’s not a name most people recognize, but it carries real weight in fighting against bacteria, viruses, and even mold. This is a quaternary ammonium compound, often called a “quat," and it’s prized by professionals and custodians for buckling down on messes nobody wants to deal with, especially in healthcare, schools, and the food industry.

How the Compound Enters Daily Life

A few years back, I spent some time shadowing a janitorial crew at a hospital. Every so often, the utility room would fill with the smell of disinfectant, sharp and unmistakable. They relied on products containing quaternary ammonium compounds just like didecyldimethylammonium bromide, especially during outbreaks of illnesses like norovirus. The faith in these cleaning agents comes from their proven track record. A 2020 CDC guidance mentioned quaternary ammonium compounds directly, emphasizing their virus-killing punch, so it’s not just word-of-mouth. This ingredient takes care of high-touch surfaces: doorknobs, bed rails, cafeteria counters, you name it. In places where soap and elbow grease aren’t enough to stop the spread of disease, this compound picks up the slack.

Questions About Safety and Environmental Impact

Nothing comes without trade-offs. Disinfectants containing didecyldimethylammonium bromide have raised questions about long-term health. If you touch surfaces shortly after they’re wiped down, or breathe in the mist from sprays too often, skin and respiratory irritation can crop up. Kids and pets face the highest risk because they're more likely to come into frequent contact with freshly cleaned floors and tables. And there’s another side: once the cleaning water goes down the drain, the compound can stick around in the environment. In the past few years, studies have highlighted concerns about these chemicals gathering in wastewater, affecting aquatic life, and even influencing antibiotic resistance.

Pulled from direct experience, the custodial team in the hospital took this seriously. They used gloves, ventilated rooms well, and made sure the cleaning solutions were properly diluted. These practices are recommended by the Environmental Protection Agency and places like the National Institutes of Health.

Moving Toward Smarter Use

As these facts become better known, businesses and organizations don’t ignore them. Alternatives such as hydrogen peroxide cleaners or steam cleaning crop up, especially in schools, offices, and places with small children. Some tech-forward companies experiment with ultraviolet light disinfection. For settings that demand total sterility, like operating rooms, the tried-and-true chemicals like didecyldimethylammonium bromide still stick around, but it makes sense to save the heavy-duty stuff for riskier spots and times.

Helping workers understand safe handling, rotating disinfectants to slow down resistance, and considering biodegradable options all play a part in making hygiene both effective and responsible. In the end, didecyldimethylammonium bromide won’t vanish from shelves overnight, but careful, informed use serves everyone better.

Understanding What We’re Using

Didecyldimethylammonium bromide gets used in plenty of disinfectants. Grocery stores, schools, and even homes lean on this chemical to keep surfaces free from bacteria and viruses. That promise sounds attractive—no one wants to risk unsafe counters or pet bowls. What gets tricky is how easily we overlook what’s in the cleaning spray we use near dinner plates, kids, or our pets’ favorite napping spots.

The Science Behind the Safety Talk

Quaternary ammonium compounds, which include didecyldimethylammonium bromide, have a track record for knocking out pathogens. The Environmental Protection Agency lists it on several disinfectant labels. Yet, government and independent researchers have pointed out that regular or careless use may irritate skin, eyes, or trigger lung reactions. If a child wipes the counter and then licks their fingers, or a cat walks across a freshly cleaned table, the risk jumps higher.

Manufacturers argue that people rarely suffer real harm, especially if folks follow printed instructions. Still, not every label gives long or detailed warnings. Many of us rush to sanitize surfaces and forget gloves or ventilation. Here’s a reality: household risks add up with repetition, especially if curiosity tempts a child or a puppy to taste or touch.

Pets Face a Different Challenge

Dogs and cats spend daylight inches from floors, or licking paws and fur. A pet stepping across a cooled surface might pick up trace residues. The ASPCA lists quats among chemicals that may trigger mild irritation or, in serious cases, poisoning. Swallowed cleaners—especially for smaller pets—bring on drooling, vomiting, or worse.

Wild claims often get made about "safe for pets" labels. My own experience as a dog walker showed how quickly even a trace of cleaner can leave a pup scratching or sneezing. A visit to the vet taught me to keep both the bottle and the just-cleaned floor out of reach.

Protecting Families and Furry Friends

A few habits make real differences. Always choosing diluted versions, rinsing surfaces pets or children will touch, and opening windows brings fresh air. Reading inserts or online safety sheets, not just the bolded parts of a bottle, helps too. Gloves keep skin away from the chemical, and good habits teach kids and teens to respect what’s under the sink.

Public safety data supports switching to soap and water for lightly soiled surfaces. If a deeper clean is needed, following application and dwell times and then going over the area with a clean, wet cloth helps a lot. Every year, poison control centers get calls about accidental ingestions from kids and pets. Knowing the number, and getting professional advice fast, pays off.

Looking Forward

Cleaning products serve an important role, especially in the era of fast-spreading infections. Balancing effectiveness against long-term safety stays at the foreground. With more green or bio-based alternatives emerging, more shoppers are demanding full ingredient lists and clear usage instructions. My hope is that more companies step up with research-backed guidance and that we keep passing down cleaning habits that value both hygiene and health.

Taking Care With Chemicals: Lessons From Real Life

Workplaces often contain substances that can harm you if you treat them lightly. I’ve spent time in laboratories and on factory floors where a moment’s inattention to chemical storage led to costly mistakes. Didecyldimethylammonium bromide calls for careful respect. This powerful quaternary ammonium compound takes down bacteria and fungi with ease, which makes it valuable in disinfectants and cleaning agents. At the same time, its strength brings risk if people cut corners on storage or handling.

Inside the Storage Area: Where Accidents Start or Stop

Store didecyldimethylammonium bromide in a cool, dry place away from sunlight. That sounds simple, but I’ve watched the consequences of ignoring this advice: chemical containers swell and leak when they spend too long in hot or humid conditions. Chemical vapors fill the air in confined spaces, and workers complain of headaches and breathing problems. Keeping storage temperatures under 25°C helps lock out those risks. Avoid moisture, too. Humidity triggers clumping, spills, or reactions you do not want to deal with. Good ventilation steps in as your best friend here. Airflow reduces the chance of dangerous buildup and keeps the area safe for you and others.

Prioritizing Safe Handling: Beyond the Basics

I have opened drums and containers filled with disinfectant compounds and felt a sting in my nose from just a careless whiff. PPE is not just a checklist item. Go for chemical-resistant gloves, safety goggles, and a lab coat or apron. That gear blocks skin contact and shields your eyes—two places you do not want didecyldimethylammonium bromide to touch. In busy workplaces, it only takes one mishandled splash or spill to ruin a day or worse.

Handling this compound with dry, clean hands makes a difference. Wet gloves or tools grab and transfer chemicals. Have running water and an emergency eyewash station close by—every facility storing disinfectants owes this to workers. Even small splashes can trigger serious irritation. The risk does not stop there. People sometimes underestimate how easily these substances can make their way into mouths or onto food. No eating, drinking, or smoking belongs anywhere near storage or handling stations.

Labeling, Training, and Community Responsibility

Clear labeling keeps accidents at bay. Mark all storage containers and include hazard warnings so no one grabs something by mistake. Think about the temporary workers or new hires—walk them through the safety data sheets, storage policy, and spill cleanup plan. I’ve watched confusion breed mistakes in facilities where training runs thin. Knowledge keeps you protected when alarms sound or mistakes happen.

Chemical safety also demands a plan for waste and leaks. Never dump unwanted didecyldimethylammonium bromide down the drain. Local environmental rules matter. If the compound escapes into the wrong place, water supplies and wildlife pay the price. Store empty containers as carefully as you do full ones. Residue causes trouble if ignored.

Simple Steps, Big Impact

Handling didecyldimethylammonium bromide safely boils down to keeping eyes open, speaking up, and refusing shortcuts. It pays to work in a team that follows the rules—not just for regulatory compliance, but for real-life safety. I trust a workplace with strong training, clear labeling, and ready safety gear. Protect yourself and your coworkers—respecting chemicals shows you respect life.

Understanding What Makes a Safe and Strong Disinfectant

Didecyldimethylammonium bromide, known among cleaning professionals as DDAB, shows up in the lists of hospital-grade disinfectants for a reason. People put it in sprays, wipes, and even mop buckets because it packs a punch against bacteria, viruses, and fungi. But mixing it right makes all the difference. Too strong harms more than germs, too weak fails to stop the spread. Using the right amount isn’t just about getting a clean surface, it’s about protecting your health and avoiding unnecessary risks.

The Range That Works—and Why It Matters

Guidelines from reliable sources like the EPA and peer-reviewed research often land between 0.1% and 0.5% DDAB for surface disinfection. Hospitals and labs usually stick to the upper end—closer to 0.3% to 0.5%—especially when cleaning up after infectious outbreaks. On routine jobs, like wiping classroom desks or cleaning gym equipment, you’ll see solutions mixed around 0.1% to 0.2%. That level deals with most germs you’re worried about in daily life. Use less, and you lose the protection DDAB promises. Regular use above these recommendations doesn’t always bring extra safety, but it does increase the risk of skin irritation, damage to surfaces, and even possible asthma in cleaning staff.

Putting the Numbers to Work in Real Life

Anyone holding the bottle needs a clear path to the right mix. Bottles should spell out how much to use per liter or gallon of water. If the label’s faded or missing, then trusted references like the CDC or government agencies have the numbers online. Pouring out a “glug” or tossing in an unmeasured capful invites mistakes. One time in a nursing home I visited, staff used double the recommended amount, hoping to stop a flu outbreak. The air in the halls turned harsh, residents coughed more, and metal handles started to corrode. The outbreak didn’t slow any sooner, but cleaning costs jumped, and maintenance spent weeks fixing the damage.

Why Not Go Stronger?

Mixing DDAB up to concentrations above 0.5% won’t always give you more peace of mind. Some viruses and spore-forming bacteria need extra contact time or a different disinfectant altogether—chlorine for example, not just a stronger DDAB. Stronger mixes raise the odds that someone, maybe a custodian or daycare worker, develops rashes or suffers breathing troubles. Keeping to well-studied ranges means cleaning up germs without leaving new problems behind.

Supporting the Facts with Science

Peer-reviewed journals and agencies such as the World Health Organization point consistently to those mid-range concentrations. Over many years, hospitals have tested what gets the job done. Researchers show that 0.1% can inactivate most enveloped viruses on clean surfaces in minutes. Heavier contamination and dirt may call for a stronger mix, but cleaning away visible soil before disinfecting does nearly as much work as bumping the concentration.

How to Make This Work Across Workplaces

The real trick isn’t just knowing the number. It’s teaching everyone who handles the stuff what the safe range looks like and why it matters. Clear charts in staff rooms, easily understood instructions, and routine checks help keep everyone on the same page. If you handle cleaning at work or home, don’t leave these steps to chance. Using the right DDAB concentration could be the easiest win in public health you control today.

Everyday Encounters and Why They Matter

Most people don’t realize how many disinfectants and cleaners contain Didecyldimethylammonium Bromide. Skim the label on a commercial wipe or hospital-grade surface spray, and odds are good you’ll see its long chemical name in the ingredient list. This compound helps kill bacteria, fungi, and some viruses—a key line of defense for many facilities. Plenty of us work, study, or spend time in places treated with these potent cleaners.

Health Hazards Aren’t a Distant Worry

Work in the cleaning industry, healthcare, or even in facility management and you probably know someone who complained about rashes, eye redness, or coughing after handling products with “DDAB.” Peer-reviewed studies and safety sheets make it clear—touching or inhaling this chemical can irritate the skin, eyes, and lungs. Sometimes these reactions show up as a burning sensation, itching, or even headaches if exposure is frequent. A review published by the National Library of Medicine draws a clear connection between prolonged contact and asthma-like symptoms in workers.

Disinfectants often bring good intentions—keeping us safe from germs. Still, when used in poorly ventilated spaces or mixed with hot water, vapor can hang in the air, leading to accidental inhalation. My cousin used to clean offices overnight, and he’d mention “the chemical smell that lingers.” Over the months, he developed chronic sinus irritation. The substances we use, without much thought, can damage our own defenses before we notice the warning signs.

Environmental Impact Deserves Attention

One overlooked issue relates to where the run-off goes. After surfaces get scrubbed, residual chemicals get washed down drains and enter local water systems. Research funded by the European Commission indicates that quaternary ammonium compounds remain stable in water, putting aquatic life at risk and even disrupting microbial activity in soil. Over time, persistent exposure to high levels of these compounds threatens more than just targeted pathogens—it throws off the environmental balance most people take for granted.

Reduction and Protection: Real Solutions

Some solutions don’t involve overhauling everything. Switch to the least concentrated version of a cleaner that gets the job done. Rotate products, so no one chemical becomes the default for every cleaning task. Provide gloves and proper masks, especially for workers who handle concentrated formulations. Train people to avoid mixing quats with other chemical cleaners, as combining products often produces more irritating fumes. Manufacturers and employers together can choose safer alternatives, such as hydrogen peroxide-based disinfectants or hypochlorous acid, which break down faster in the environment and leave fewer residues.

Basic changes—opening windows, using fans, or cleaning during off-hours—reduce accidental buildup of airborne chemicals. Businesses can look at investing in air filtration systems for spaces that need regular heavy-duty cleaning. As more evidence piles up linking chemical exposure to real health effects, routines must adapt. Precaution isn’t just a slogan—it matters for every person and community exposed, often without even knowing the risks.