Dodecyldimethylethylammonium Bromide: A Ground-Level Commentary

Historical Development

Dodecyldimethylethylammonium bromide, a quaternary ammonium compound, started its journey about a century ago. Folks in the early chemical industries took a keen interest in quats because they noticed a link between structure and microbe-killing power. As hospitals battled infectious diseases and public sanitation ramped up, formulators searched for tools that could wipe out germs without causing massive harm to users. Scientists experimented with alkyl chains and different ammonium salts, figuring out which could deliver the punch without breaking the bank. With the twelve-carbon tail and simple structure, dodecyldimethylethylammonium bromide fit right in with growing lists of antimicrobial agents. Documentation in scientific literature ramped up in the mid-to-late 1900s as production processes became more standardized and available to large-scale buyers.

Product Overview

Dodecyldimethylethylammonium bromide often gets tossed into the bucket of cationic surfactants. With a long dodecyl (twelve-carbon) tail, two methyl side groups, and an ethyl group, it manages to pack a punch in detergency and surface activity. In the lab, it comes across as a white, crystalline solid that dissolves in water with ease. Its main selling point lies in its antiseptic and disinfectant values. Unlike old-school soaps that rely on fatty acids, this one latches onto cell membranes and pokes holes where microbes can’t repair the damage. It does double duty: cleaning up surfaces and lowering surface tension so active ingredients get evenly spread.

Physical & Chemical Properties

A big part of understanding any chemical involves looking at what it feels and acts like. Dodecyldimethylethylammonium bromide’s molecular formula, C15H34BrN, gives it a molar mass of about 324.34 g/mol. It typically shows up as a white or off-white powder, stable at room temperature and nonvolatile in most open-air settings. You don’t find any sharp odor, but the solid will cake up under humid conditions. It dissolves rapidly in both water and ethanol and creates stable, clear solutions. As a cationic surfactant, it offers a positive charge—so it binds tight to negatively charged cell walls and dirt particles. It melts at around 187°C, offering solid shelf-life and handling flexibility, and behaves well through transport and bulk storage.

Technical Specifications & Labeling

Product quality depends on more than chemical composition; regulatory labeling and manufacturing methods weigh in heavily. Purity usually sits north of 98%, with moisture content kept below 2%. Packaging needs to protect the material from exposure to air and dampness—poly-lined fiber drums or high-density plastic containers do the trick. Regulatory details, such as CAS number (a key identifier in international inventories) and recommendations for protective equipment, sit on the front of the product sheet. Handling instructions stress avoiding powder inhalation and keeping material away from open flames—basic, sensible precautions for both small-batch labs and industrial factories. There’s no room for cutting corners with labeling, since mishandling even a mild irritant can set off a safety chain reaction.

Preparation Method

Preparation always feels like a chemistry lab classic. Take dimethylethylamine and react it with dodecyl bromide under reflux. The result is an alkylation reaction—simple in design, a bit stubborn when scaling up. Every chemist who’s worked with quaternary ammonium compounds has chased purity, using recrystallization from water or an alcohol. Purification matters because leftovers can throw off both toxicity risk and performance in the field. Even minor byproducts, if not handled, can introduce skin irritation or cloud an otherwise transparent cleaning solution. Operators weigh temperature control, stirring speed, and timing to squeeze each percentage point of yield.

Chemical Reactions & Modifications

Dodecyldimethylethylammonium bromide doesn’t play tricks in most reactions—it’s stable in neutral and mild alkaline settings, but mixing with strong oxidizers, acids, or basic groups kicks up byproducts or breakdown. Some researchers go after modifications of the alkyl chain or counterion to alter its antimicrobial spectrum—changing from bromide to chloride lets it play in slightly different markets or formulation environments. Thanks to its cationic charge, it forms complexes with various anionic polymers and can precipitate in the presence of certain soaps and detergents. In specialty applications, chemists try swapping different chain lengths or adding fluorinated groups to see whether improved resistance to breakdown or increased targeting of hard-to-kill bacteria can be achieved.

Synonyms & Product Names

This substance picks up plenty of aliases—N-Ethyl-N,N-dimethyldodecan-1-aminium bromide and Dodecyl(dimethyl)ethylammonium bromide top the list. Chemical companies market it under house brands, with product codes stuck on the end. For regulatory and import/export work, sticking with the standard IUPAC and CAS number keeps paperwork smooth and avoids legal headaches. Generic “quats” or “cationic surfactant” tags help field technicians and cleaners remember what it does at a glance, since few outside the chemistry world memorize these tongue-twisters.

Safety & Operational Standards

In the world of chemical safety, hard lessons shape every protocol. Anyone who’s worked with quaternary ammonium compounds knows gloves aren’t optional. Prolonged skin contact risks irritation, drying, or sensitization. The powder form can kick up dust, so splash goggles and respirators keep sneezing to a minimum in the plant. Storage should be cool, dry, and away from food or acids. Documented uses show the chemical doesn’t accumulate in the body, but accidental ingestion or inhalation in large amounts can trigger trouble—nausea, coughing, or more severe symptoms in folks with respiratory issues. Hospitals, cleaning contractors, and manufacturers drill their people on proper dilution and spill clean-up. Local regulations set allowable discharge levels, as aquatic organisms feel the impact of residual quats dumped into sewage or stormwater.

Application Area

Quats like dodecyldimethylethylammonium bromide fill important roles across industries. In healthcare, beds, tables, and surgical tools need constant attention, and this chemical takes down bacteria that linger long after most surface cleaners wear off. Food processing plants lean on it for conveyor belts and cutting surfaces, since greasy buildups and biofilms can threaten entire batches. Municipal water systems use it to blast biofilms out of pipes and tanks, improving flow and water safety. In the home, it sneaks into fabric softeners and bathroom cleansers, binding to fibers to keep them lint-free and germ-resistant. You find it doing heavy lifting in animal husbandry—disinfecting stalls and equipment without causing toxicity to livestock. Personal care, textile finishing, industrial waste treatment—a never-ending list.

Research & Development

R&D moves at its own pace, sometimes racing to match outbreaks or new regulatory standards. Over the past few years, concern about superbugs has challenged scientists to refine, combine, or rotate old quats to keep microbe resistance at bay. Researchers test derivatives with longer or shorter chains, or design blends with secondary ingredients that block adaptive responses in bacteria. Analytical labs plot the breakdown rates and environmental fate of each variant, fine-tuning recipes so product runoff doesn’t choke rivers or disrupt wastewater plants. Industry-government partnerships fund large-scale screening programs, especially as worker safety and biohazard risks draw sharper scrutiny. In my years working with startup manufacturers, the scramble to prove a product “greener” or less toxic has driven both small-scale lab trials and big pilot runs.

Toxicity Research

Toxicity often divides camps into cautious optimists and doom-sayers, but history teaches caution. Acute toxicity for humans lands on the lower end when compared to most industrial pesticides, yet repeated or high-concentration exposure creates problems: skin dryness, rashes, and sometimes respiratory distress. For aquatic life, sensitivity jumps up dramatically. Algae, fish, and invertebrates take the biggest hits, leading to increased pressure for closed-loop wastewater recycling in chemical-heavy industries. Ongoing work measures long-term effects on non-target organisms and potential for bioaccumulation, while reformulations promise less harm downstream. Transparent reporting on exposure rates in the workplace and routine baseline health checks catch earlier warning signs. Regulators keep one eye on published literature and another on persistent reports of irritation in the field.

Future Prospects

Changes in sanitation demands, global movement of people and products, and the slow-but-steady shift toward green chemistry set the stage for the next act. As resistant strains of bacteria show up in places they never did before, demand for “smart” disinfectants with multiple modes of action grows. Manufacturers tinker with ways to reduce environmental persistence through faster breakdown or improved wastewater remediation. More rigorous toxicity screens on analogs and formulations could push some out while opening the door for new blends. Within the cleaning, water treatment, and healthcare fields, folks want products that combine strength with safety—not just on paper, but across daily use, disposal, and long-term impacts in the environment. For now, quats like dodecyldimethylethylammonium bromide will keep a place on the shelf, but frequent re-evaluation remains a must for everyone who makes, handles, or relies on them.

More Than Just a Complex Name

Dodecyldimethylethylammonium bromide might sound intimidating, but it’s a workhorse that pops up in labs and industries far more than most people realize. I’ve crossed paths with this compound during my years in chemical research, usually with latex gloves on, a pipette in one hand, and the scent of disinfectant in the air. Sometimes, the everyday things we trust for cleanliness or stability rely on molecules like this one.

The Cleaning Powerhouse: Disinfectants and More

Many hospital janitors probably don’t know this name, yet they wipe down surfaces with solutions containing this exact molecule. That’s because dodecyldimethylethylammonium bromide falls into the quaternary ammonium salts family—a group known for their ability to tackle bacteria, fungi, and viruses. Studies continue to back up their safety and effectiveness for cleaning in sensitive places like hospitals and food factories, keeping infection risk lower.

At home, it plays a part in some surface cleaners too. Its antibacterial punch helps knock down the germs lingering around kitchens and bathrooms, offering a fresh-smelling, less risky space. Some researchers raise concerns about overuse of quats (as they’re called), but responsible use reduces the chance of creating overly resistant germs.

Sweeping Away Problems in Science Labs

Any scientist who has handled DNA, proteins, or cell cultures knows reproducibility gets tricky in the lab. Dodecyldimethylethylammonium bromide brings reliability to the table. In biochemistry labs, its surface-active nature means it gets used as a detergent. When researchers want to break open cells, this compound disrupts membranes, helping release the contents without wrecking everything inside. It keeps proteins happy in water—or at least less likely to clump or fall apart. In my own experience, switching to a better detergent can save days or even months of wasted work.

This compound also steps in during gel electrophoresis, a standard method for separating biological molecules. Here, it assists by evenly coating proteins, so they travel consistently through the gel. This routine utility makes it a backbone in numerous published experiments, and laboratory manuals continue to list it among their preferred detergents for reliable results.

Potential Risk: Environmental and Health Footprints

Quaternary ammonium compounds, including dodecyldimethylethylammonium bromide, do not vanish after washing down drains. While their chemical stability makes them useful, it also means traces linger in water streams. Researchers have measured these compounds in water supplies across Europe and North America, linking high levels to toxicity in aquatic organisms. Over time, this could stress fish populations and disrupt food webs.

Health professionals have raised eyebrows, too. Frequent handling without proper protection can irritate skin or trigger allergic responses. That hits home for those cleaning hospitals or working daily in chemical plants. Following clear safety protocols and wearing proper gear makes a difference—my own slight rash, years back, disappeared after stricter glove use.

Rethinking Solutions

Solving these challenges isn’t easy, but careful chemical management helps. Manufacturers focusing on safe disposal and green chemistry see results. Substituting less persistent alternatives, developing better wastewater treatment filters, and revisiting how much disinfectant companies really need to use pays off for people and the planet. The science community has started encouraging more transparency about what goes into cleaning products and how these choices affect both health and water systems. As someone who’s spent more hours handling this chemical than I care to count, I take comfort knowing that attention to detail—both in the lab and in policy—promises a safer path forward.

Looking Closer at This Chemical

Dodecyldimethylethylammonium bromide pops up in laboratories and cleaning products. Chemists appreciate how it helps break down oily stains and disrupts cell membranes in bacteria. This sounds useful, but handling any chemical like this shouldn't ever feel routine or casual.

What Happens on Contact?

My own lab time showed me, even years out of school, that safety goggles and gloves always help. Dodecyldimethylethylammonium bromide can irritate the skin and eyes. Breathing in its dust makes your throat burn and sends you coughing. NIOSH, the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health, sets strict airborne limits for this type of ammonium compound. You get headaches, dizziness, and difficulty breathing at high exposure.

The Real Risks

Not many folks outside scientific jobs hear about quaternary ammonium compounds, but stories filter through the chemical safety network. One research technician missed the warning labels, skipped the gloves, and ended up with red, burning hands for a week. He reported the mistake during a monthly safety meeting—it became a lesson for new hires. Long-term exposure links to greater asthma risk, and people with sensitive skin sometimes develop rashes that don’t disappear overnight.

The Environmental Protection Agency lists similar bromide and chloride versions as toxic to aquatic life. Spilling this down the sink at home or work does more harm than most think. Some states push users to collect waste and treat it as hazardous. Even dilute rinse-water, after cleaning lab glassware, goes into special disposal—not into the regular drain. These simple steps keep sewer systems and local ponds cleaner for wildlife.

Why Take Extra Steps?

Plenty of surfaces need disinfecting and plenty of industries use surfactants. The safest approach borrows from hospital routines: put on nitrile gloves and goggles. Always work near a fume hood or at least with open windows. Keep a clean workspace by storing bottles away from heat and food. I still hear colleagues say, "We’ve never had an accident," but that kind of mindset gets people in trouble.

If something splashes on your skin or eyes, rinse right away for fifteen minutes and call for help. Don’t just shrug it off. I’ve watched old professors run these drills with students—even stubborn kids understand the message after that.

Better Labels and Training Matter

Clear warning labels cut bad surprises. A rushed morning often tempts people to skip reading instructions. Refresher training sends everyone back to basics. Chemical suppliers carry Safety Data Sheets for every shipment. My own department posts them near each lab bench, a requirement since the nineties. New researchers must sign a paper confirming they’ve read all the rules. These habits sound repetitive but help prevent long-term harm.

Smart Alternatives and Next Steps

Some organizations rethink using dodecyldimethylethylammonium bromide where a greener surfactant does the job. Biodegradable cleaners reduce the risk in schools and homes, and product developers keep searching for new formulas that clean well without raising health concerns. Until the perfect substitute arrives, strict safety routines remain essential. Lab technicians, janitors, and everyone in between benefit from preparation, and everyone goes home safe at the end of the day.

Why This Compound Calls for Attention

Dodecyldimethylethylammonium bromide stands out as a surfactant and disinfectant in labs and industries, especially in cleaning and hygiene products. Its value in research and commercial use all traces back to its chemical stability. Storage isn’t just a checkbox; if this material turns bad, it doesn’t just lose punch—it might create waste or, worse, safety risks for anyone handling it. I’ve seen the fallout when simple products went wrong in storage: clumped powders, odd smells, or changes in color that set off all kinds of alarms. Nobody wants to throw out a costly batch because the cap sat loose or sunlight streamed through a window at the wrong time.

Humidity and Moisture: The Biggest Enemies

This chemical pulls moisture out of the air like a sponge. Left on a shelf with high humidity, it can start to cake, which makes dosing inconsistent and creates cleaning headaches. I learned the hard way in a crowded storeroom how clotted samples can compromise high-stakes research. Best defense? Store it in a tightly sealed container. I prefer using airtight glass or heavy-duty plastic jars with screw caps. Tossing in a silica gel pack helps soak up stray moisture, keeping things dry and easy to handle. Keeping it in a cool, dry cabinet—definitely not out in a steamy storeroom—protects both the product and the team using it.

Heat, Light, and the Problem of Degradation

Exposure to heat can nudge this chemical out of its stable zone, prompting breakdown. It doesn't like swings in temperature. So, a spot away from heaters, boilers, or sunny sills is smart. Sunlight also tweaks chemical bonds over time. I’ve watched plenty of samples fade or morph when someone stacked chemicals near lab windows. For this one, the darker, the better—closed, opaque containers inside shaded cupboards or lab fridges (if recommended on the label) work fine. Room temperature usually suffices, but checking the manufacturer’s details matters for peace of mind.

Safe Handling and Accident Prevention

Strong labeling and routine checks keep surprises at bay. My shelves are marked with clear names, hazard warnings, and last check dates. Spills count as more than a nuisance with chemicals like this. Goggles, gloves, and a tidy workspace shield skin and eyes. I learned in my first lab job that even seasoned colleagues can let things slide if storage gets sloppy—and cleaning up becomes a race the clock when powders drift or mix. If you spot discoloration, odd smells, or cracked containers, that’s the moment to swap out stock and update logs. Staying vigilant pays off every time.

Disposal and Environmental Responsibility

Expired or degraded chemicals should never hit the drain or regular trash. I always reach out to the building’s hazardous waste handler or use a dedicated chemical waste program. Proper disposal cuts down on environmental risks and protects water sources—nobody wants this stuff where it shouldn’t be. Safety Data Sheets (SDS) tell the proper disposal steps, and following them protects not just the user, but the community as well.

What an Attentive Storage Routine Delivers

Paying close attention to each bottle’s condition, using strong containers, and watching temperature and moisture make a big difference. Respect for the chemical often translates to safer labs and workplaces, with less waste and fewer mishaps. Chemicals demand a certain diligence, and for dodecyldimethylethylammonium bromide, tight controls keep everything running smooth—for the science, the business, and the people behind each project.

Chemical Dangers Land in Your Hands

Dodecyldimethylethylammonium bromide often shows up in disinfectants and cleaning products. It’s a tough surfactant, breaking down grime but not always disappearing as quickly as we might hope. I’ve dealt with a few chemicals like this in my research days, and safe disposal calls for more thought than simply pouring it down the drain. Ignoring the risks brings environmental damage and possibly harms water treatment processes.

Why Safe Disposal Matters

The stuff isn’t just soap. In large doses, quarternary ammonium compounds disrupt aquatic life and upset the balance in wastewater facilities. The Environmental Protection Agency highlights cases where improper chemical disposal killed off microbes inside treatment plants, leading to contaminated water heading back into the river. These incidents often started in people’s homes and small labs. That’s why handling leftovers properly matters for everyone.

Practical Steps for Getting Rid of Leftovers

Many of us have the instinct to rinse out empty bottles or toss small leftovers into the trash. That move turns a household problem into a bigger community issue. Most city guidance treats this compound as hazardous waste, so the cleanest route uses local hazardous waste collection services. Every county I’ve lived in set aside days a few times a year to collect old paint, solvents, and surplus cleaners. Check city or county websites—they keep lists of what they accept.

Dorm rooms and offices often wind up with small beakers of old lab chemicals or cleaning agents. Label every container, no matter how little is left, and keep different chemicals from mixing. Transport them in sealed, leak-proof containers, and never combine leftovers to ‘save space’. During college, my lab once got fined over a mismatch between labels and containers; a simple mistake introduced new hazards for workers and the Earth beneath us.

Alternatives to Dumping: Rethinking Use and Purchase

Only buy what you plan to use within six months. If you find extra, see if you can return it to a supplier or swap supplies with a neighbor or another department before considering disposal. Some manufacturers offer take-back programs for surplus stock, especially in industrial settings. This reuse saves money and spares waste stations.

Across industries, people reduce their reliance on hazardous surfactants by replacing them with safer alternatives. Plant-based cleaners work for some jobs, limiting the need to juggle dangerous leftovers. At home, using up the last drop means less to throw away, which simplifies the next step.

What Law and Community Have to Say

State and local rules treat compounds like this as threats to clean water and soil. Heavy chemical dumping has led to lawsuits and high cleanup costs for both companies and homeowners. The EPA maintains records of Superfund sites where improper disposal polluted drinking water, costing millions in repairs. Everyone’s property values and health get tangled in these mistakes.

Many cities run year-round efforts to help residents hand off tricky chemicals safely, free from judgment or fines for odd leftovers. Their goal lines up with yours: protect your neighborhood’s water and land.

Final Thoughts

Whether in a school lab, industrial site, or home garage, every step you take to dispose of dodecyldimethylethylammonium bromide with care has real impact. Ask questions, follow your local guides, and focus on using less so that fewer hazardous materials threaten the places we live and work.

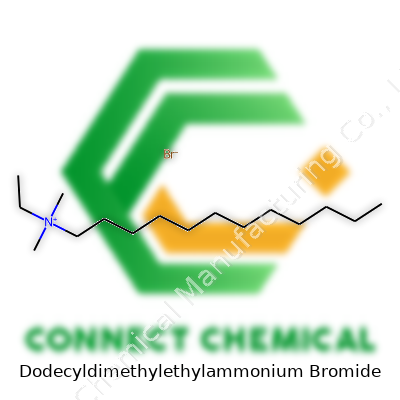

Understanding the Structure

Dodecyldimethylethylammonium bromide may sound wordy, but the structure comes down to a few recognizable parts. Picture a nitrogen atom at the core, bonded tightly to three groups: two methyls, one ethyl, and a long dodecyl chain. That’s twelve carbons in a row, like a piece of spaghetti, stuck to the end of a nitrogen. Right next to that, the bromide ion balances things out. This setup—one nitrogen, four carbon-containing “arms,” and a counterion—puts this molecule in the quaternary ammonium family.

Why Structure Shapes Function

In the lab, I learned that long chains attached to a charged group can break apart grease and kill bacteria. With dodecyldimethylethylammonium bromide, that dodecyl tail doesn’t just add heft. It forms a kind of “grease hook,” digging into oily molecules while the charged nitrogen sticks to water. This feature explains why cleaning products, disinfectants, and surfactants often favor such compounds. The positive charge on the nitrogen plays a huge part in this behavior. Water forms a loose shell around it, and oily dirt sees the long tail as a place to hide. As a result, when I’ve mixed solutions of this compound into water, it quickly finds dirt, wraps it up, and lifts it away.

Health and Handling: What to Know

Some people overlook safety when working with quaternary ammonium compounds. First time I handled dodecyldimethylethylammonium bromide, I remembered the sting it left after careless handling. Skin dryness, eye irritation, and mild burns crop up if you ignore gloves and eye shields. Papers from the National Institutes of Health highlight that repeated exposure causes more issues, from allergies to breathing trouble in sensitive folks. Beyond the lab, using cleaners with similar formulas in poorly ventilated bathrooms can bring coughing or sneezing.

This concern matters more now, since quats pop up everywhere in sanitation. I once visited a school that switched to heavy-duty disinfectants during flu season and noticed parents voicing concern about chemical residues. Science backs up that these residues, especially in small kids, raise the risk of skin irritation and even low-level asthma. The long dodecyl tail means the molecule doesn’t break down as quickly as simpler ones, leading to buildups if rinsing gets skipped. Wastewater stories repeat this trouble: after several days, water treatment centers detect quaternary ammonium remnants sticking around, sometimes affecting helpful bacteria in their systems.

Possible Solutions and Responsible Use

This structure gives dodecyldimethylethylammonium bromide impressive cleaning power. It’s tempting to pour a little more and scrub a little less. Based on studies and personal experience, using measured doses—never more than directions call for—cuts risk and waste. I once trained janitorial staff to switch from “eyeballing” to measured dispensing pumps, which slashed both chemical costs and accidental skin contact.

Improved formulations exist on the market, too. Some manufacturers add ingredients to help the molecule rinse off better or to break down faster in the environment. Communities near water plants often push local governments to set rules limiting how much of these compounds settle in the waterways. Support for research continues to grow, targeting compounds that do the same cleaning but degrade faster, contain less toxic side-products, or show minimal impact on aquatic life. Strict lab habits and good labeling reduce accidental mix-ups. Access to up-to-date chemical safety data makes a bigger difference than any quick-fix kit.

The structure of dodecyldimethylethylammonium bromide illustrates how chemistry reaches into daily life. Cleaning, disinfecting, and even the local water supply show the mark of this single molecule, shaped as much by twelve carbons in a row as by a charged head group and a careful counterion in tow.