N-Methylimidazolium Bis((Trifluoromethyl)Sulfonyl)Imide: A Commentary

Historical Development

The world of chemistry has a long track record of pushing boundaries, and ionic liquids like N-Methylimidazolium Bis((Trifluoromethyl)Sulfonyl)Imide show just how creative researchers can be. In the late twentieth century, curiosity about non-volatile solvents drove research groups in Japan, Germany, and the United States to look for safe ways to conduct reactions outside the limitations of traditional solvents. N-Methylimidazolium-based ionic liquids began getting real attention after the introduction of bis((trifluoromethyl)sulfonyl)imide anion in the 1990s, when academics realized its broad electrochemical window, low viscosity, and robust thermal stability. Engineers and chemists sought ways to reduce volatile organic emissions from labs and factories, and this compound fit the bill with its very low vapor pressure. Instead of shuttling around hazardous or highly flammable solvents every day, researchers were given a powerful tool with high chemical stability, and low toxicity in many contexts.

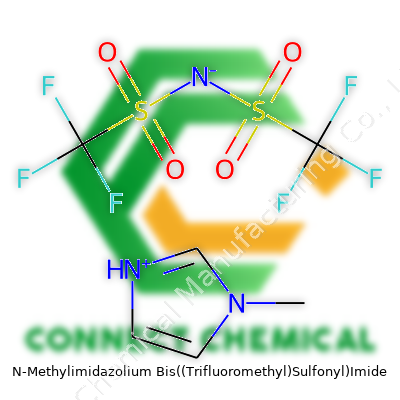

Product Overview

N-Methylimidazolium Bis((Trifluoromethyl)Sulfonyl)Imide, usually abbreviated as [MIM][NTf2] or simply “methylimidazolium ionic liquid,” presents itself as a clear, often faintly yellowish liquid at room temperature. The combination of a cationic imidazolium ring—bearing a methyl group on the nitrogen—and a large, highly delocalized anion, bis(trifluoromethylsulfonyl)imide, gives this compound a unique chemical personality. This pairing creates a substance that flows easily, resists evaporation, and supports tough chemical transformations. Companies in the electronics, battery, and pharmaceutical fields rely on it, not for show, but because it deals so well with heat, current, and polarity challenges. There’s less fuss about flammability and leaks, and the material also offers opportunities for “green chemistry” applications as a replacement for petroleum-based solvents.

Physical & Chemical Properties

N-Methylimidazolium Bis((Trifluoromethyl)Sulfonyl)Imide typically appears as a low-viscosity liquid at room temperature, with a melting point below zero Celsius in most formulations. Its high thermal and electrochemical stabilities make it valuable in processes running above 200°C and in systems involving strong electrical potentials, like battery electrolytes and certain electrochemical devices. The high density shows up in practical handling—bottles feel heavier compared to typical solvents. Water solubility varies based on the exact side-chain composition but tends toward moderate to low. Electrical conductivity and a broad electrochemical window find use in supercapacitors and electroplating. The liquid feels slick to the touch (lab gloves always, of course) and rapidly wets glass and metal surfaces. Its low vapor pressure cuts down on losses to the air—workers aren’t enveloped in pungent odors.

Technical Specifications & Labeling

Suppliers print detailed technical sheets with information like molar mass, purity levels (usually above 99%), color, water content (typically below 0.2%), and storage recommendations. Certification often includes testing for halide impurities, acidity, or metal traces, because these can wreck sensitive reactions. Labels feature the chemical name, UN numbers for transport, CAS number, and the most current hazard pictograms. Shipments always come in tightly sealed, opaque bottles, since light or moisture exposure slowly shifts the properties over time. Any responsible source provides batch-specific certificates with analytical results—chloride or residual solvent levels, for instance—since applications in electronics or pharmaceuticals tolerate almost no contamination. I’ve seen colleagues audit these specs with portable GC-MS in the lab before starting big synthesis runs, to avoid surprises after a major outlay of time or materials.

Preparation Method

Chemists usually start by alkylating imidazole to get N-Methylimidazole, which reacts with an alkylating agent like methyl iodide to produce N-Methylimidazolium iodide. This intermediate then undergoes ion-exchange—mixing with a source of bis((trifluoromethyl)sulfonyl)imide, typically lithium or sodium NTf2. After stirring in water or acetonitrile, the methylimidazolium salt extracts into dichloromethane or another phase. Rigorous washing removes halide and metal residues, followed by distillation or solvent removal under vacuum. Cleanliness counts; trace halides, water, or protic impurities all weaken the liquid’s special properties. In commercial settings, the process scales up with filtration, distillation columns, and nitrogen purges, so that tons of material remain just as pure as what’s produced in smaller flasks.

Chemical Reactions & Modifications

N-Methylimidazolium Bis((Trifluoromethyl)Sulfonyl)Imide dislikes nucleophilic attack on its anion, which helps it stay stable in harsh conditions. The methyl group on the imidazolium can, in principle, be swapped for longer alkyl chains to alter viscosity, melting point, and solubility. Researchers explore these modifications to fine-tune the liquid for different devices or chemical transformations. Strong oxidizers and certain acids can eventually decompose the ionic pair, but most organic and inorganic reagents cannot. While not the right fit for every chemistry, its ability to dissolve both polar and nonpolar molecules opens up catalysis, metal extractions, and controlled crystal growth. In one interesting example from my own bench work, I’ve seen these liquids act as both solvent and catalyst in cycloaddition reactions, helping deliver higher yields in tough carbon-carbon bond forming steps.

Synonyms & Product Names

Chemical circles call it [MIM][NTf2], N-Methylimidazolium bis(trifluoromethylsulfonyl)imide, or 1-methyl-3-imidazolium bis(trifluoromethylsulfonyl)amide. Product names in catalogs might add designators like “EMIM” for ethyl variants or list the ionic liquid under the “IL” segment, such as “IL-10227.” Keeping track of synonyms matters: small labeling mix-ups between methyl and ethyl or propyl derivatives can derail a process, because these side chains shift the physical and chemical behavior significantly.

Safety & Operational Standards

Reports show N-Methylimidazolium Bis((Trifluoromethyl)Sulfonyl)Imide brings lower acute toxicity than many solvents, but safety remains non-negotiable. Industries using the liquid enforce strict containment, personal protective equipment, and thorough ventilation. Safe transport protocols stem from international chemical safety guidelines. Teams train for spill response and know how to neutralize and contain leaks—though incidents rarely escalate due to the fluid’s low volatility. Waste must stay out of waterways, since the anion resists rapid biological breakdown. I’ve walked through factories where automated solvent recycling units recover and purify ionic liquids, reducing both environmental impact and raw material bills. Still, researchers and plant engineers should review new safety data as it gets published, since toxicity and chronic exposure data keep improving and shift best practices.

Application Area

N-Methylimidazolium Bis((Trifluoromethyl)Sulfonyl)Imide pops up across industries because of its standout combination of chemical stability, thermal resilience, and electrical properties. Battery manufacturers prize it as an electrolyte for lithium-ion and next-generation battery designs aiming for higher stability and longer lifetimes. Electronics makers count on it for electroplating specialty metals and in chip fabrication processes where no stray ions must disrupt sensitive circuitry. Pharmaceutical chemists like the solvent’s ability to separate or crystallize active ingredients in hard-to-handle synthesis steps. Catalysis researchers take advantage of its thermal and chemical footprint to produce plastics, fuels, and fine chemicals with fewer byproducts. Green chemists see a chance to trim reliance on flammable or toxic organic solvents, reducing waste as companies shift toward sustainability.

Research & Development

Academic and industrial labs keep N-Methylimidazolium Bis((Trifluoromethyl)Sulfonyl)Imide in focus. Research projects probe new side chains, seek to model solvent effects in computer simulations, and examine its role in activation or stabilization of intermediates. Funding agencies increasingly back projects that explore recyclable or bio-based versions of ionic liquids to sidestep reliance on fluorinated building blocks. Patent filings show companies expect broad commercial impact, especially as battery and semiconductor industries continue to grow. My own team has explored the influence of slight structural tweaks—swapping a methyl for an ethyl—to nudge melting points or solubility in targeted directions, in the hope of unlocking new reaction types.

Toxicity Research

Toxicologists approach N-Methylimidazolium Bis((Trifluoromethyl)Sulfonyl)Imide with careful testing. Animal studies point to low acute toxicity; accidental skin contact or inhalation, though, can cause irritation and should not be dismissed as risk-free. The anion itself has raised questions about persistence and possible ecological harm. Regulatory groups call for ongoing research into biodegradability and chronic impacts, especially if ionic liquids become mainstay substances in major industries. Life-cycle and environmental fate studies have begun, but as with many new chemical tools, unanswered questions remain. Until a longer-term picture comes into focus, responsible labs handle all ionic liquids as potentially problematic if released out of controlled settings.

Future Prospects

N-Methylimidazolium Bis((Trifluoromethyl)Sulfonyl)Imide stands at a crossroads for industrial chemistry. On one side, new applications for batteries, supercapacitors, plastics, and specialty pharmaceuticals draw interest and investment. Firms and universities run pilot-scale syntheses and try to lower cost and improve recycling. On the other, growing public and regulatory scrutiny around fluorinated chemicals presses researchers to invent next-generation materials that balance performance and safety. Long-term, ionic liquids like this one either evolve towards improved environmental credentials, or face replacement by greener alternatives. Every leap forward will depend on close collaboration between academia, industry, regulators, and the people who actually handle these chemicals on the ground, ensuring both progress and responsibility go hand in hand.

Stepping Into The World of Ionic Liquids

A lot of lab benches get crowded with glass beakers and the old standbys like sodium chloride. Tucked in between the caffeine and the caffeine substitutes, someone might catch sight of a tongue-twister – N-Methylimidazolium Bis((Trifluoromethyl)Sulfonyl)Imide. It isn’t exactly a household name. But many modern technical advances lean on deep science with names that don’t roll off the tongue. This compound belongs to the ionic liquid family, a family that keeps showing up in both research and industry for reasons anyone who hates sticky messes would appreciate: it barely evaporates, isn’t flammable under normal lab conditions, and can often dissolve materials that water can’t touch.

Battery Technology Leaps Forward

Reaching for longer-lasting gadgets means relying on breakthroughs in batteries. The lithium-ion battery market hungers for electrolytes that won’t easily catch fire or degrade. N-Methylimidazolium Bis((Trifluoromethyl)Sulfonyl)Imide steps in here. Its stable, non-volatile behavior makes it a friendly face for companies experimenting with rechargeable batteries. Some studies focus on its role as an electrolyte that resists breakdown much longer than old-school solvents. This reliability can stave off explosions and device meltdowns. Growing up with stories of phones catching fire in people’s pockets, the value of safety in everyday electronics makes immediate sense.

Green Chemistry and Cleaner Tech

Research labs chase green solutions. Traditional volatile organic solvents keep chemical manufacturing cheap, but spill headache-inducing fumes and risk accident. Ionic liquids like this one flip the script. They break down organic leftovers and separate mixtures with less hazard and lower emissions. Some start-up companies push for “greener” chemical processes in everything from extracting rare metals (think microchips and magnets in your hybrid car) to pharmaceuticals. I always hold my breath a little less in a lab that leans on less-toxic alternatives.

Challenges and Paths Forward

There’s a catch. These ionic liquids sometimes come with sticker shock, which pushes big chemical companies to look for ways to recycle them or find cheaper building blocks. Sourcing fluorinated compounds can also add its own environmental burden. Instead of relying solely on new chemicals, many researchers probe methods for using these ionic liquids in closed-loop processes. This means grabbing used solvent and scrubbing it for another go rather than dumping waste into the environment.

Towards Broader Impact

The more common these materials become, the more I notice them drifting out of cloistered chemistry journals into real-world products. I’ve seen electrolytes with higher thermal stability showing up in prototypes for grid storage, fuel cells, even specialty lubricants for situations where you’d rather not take flammability risks—think aircraft electronics and satellites. Their less-volatile profile is crucial during long operating hours or in remote locations.

Wide adoption will depend on cost dropping and better information about exactly what happens when these liquids meet soil and water. I see chemists and engineers leaning harder into lifecycle analysis, trying not just to perfect performance but to keep the “green” promises of these molecules. Given the surge in demand for safer, smarter energy and manufacturing, it makes sense to keep a sharp eye on both their promise and their pitfalls.

Storage Rules Aren’t Just Red Tape

Growing up, my dad kept bleach and paint thinner in a locked cabinet, away from the kitchen and bathroom. He didn’t trust warning labels alone—he’d seen too many horror stories on the news. This personal instinct for caution reminds me how chemical storage rules get written in blood—often after enough people have suffered when rules were skipped.

Temperature, Light, and Air: More Than Just a Checklist

Some chemicals react badly if you give them a little sunlight or the wrong breeze. Take hydrogen peroxide. Light and warmth speed up its breakdown. At a community pool job, I watched a batch bubble and fume because it got stored by a south-facing window. That single mistake wasted hundreds of dollars and forced an afternoon of mopping up chemical water—the smell stayed for days. Even something as ordinary as bleach turns nasty if mixed, by accident, with ammonia-based cleaners. Simple mistakes create dangerous vapors or breakdowns that put people at risk.

Containers Count: Not All Plastics Are Equal

A neighbor once reused old soda bottles to store gasoline in his garage. Convenience beat safety and he nearly paid for it. Certain plastics don’t hold up against strong acids or solvents. Even labels fade or peel off over time. At a lab job in college, strict labeling wasn’t just about looking neat: it meant you don’t accidentally grab acetone instead of isopropyl alcohol, or open a container that spent months weakening in the wrong plastic shell. Choosing the right bin, drum, or bottle keeps contents stable and workers safe. It isn’t just about spills—it’s about stopping contamination that nobody can see until it’s too late.

Ventilation Limits Headaches and Disaster

Not every chemical gives off visible fumes, but that doesn’t mean the air stays safe. In smaller businesses or older buildings, poor airflow means dangerous gases can sneak up and make people sick. I’ve worked with people who got headaches and coughs from vapors they didn’t even notice, only to find out later that a simple vent hood would have done the trick. Some chemicals, like acetone or lacquer thinner, create explosive vapors if they're stored in bulk without proper air movement and spark-free environments. Effective storage spaces look beyond the container and include real plans for keeping air safer, especially in shared workspaces.

Regulations and Responsibilities

Local and national rules matter more than most folks admit. The EPA and OSHA publish clear standards for a reason—one need only look at recent chemical plant accidents to see what happens when corners get cut. The fines sting, but the health consequences linger far longer. Documentation isn’t just paperwork for inspectors; it tracks what’s on site, how long it’s been there, and the safest way to clean up when spills occur. Fire marshals, insurance companies, and public health officials expect that someone always knows what’s getting stored, where, and how it’s protected from the unexpected.

What Better Storage Looks Like

In the real world, thoughtful chemical storage always beats last-minute improvisation. Use sturdy, compatible containers with clear, chemical-resistant labels. Keep incompatible products apart, especially acids and bases, and invest in flammable storage cabinets where rules demand it. Keep everything out of direct sunlight, away from extremes of heat and cold, and check ventilation as part of routine safety checks. Teach everyone who touches these materials—not just managers—what the risks look like, and give them the freedom to call out questionable setups before mistakes turn costly. That’s not just law; it’s common sense built through generations of bad experiences and better solutions.

A Look at This Popular Ionic Liquid

N-Methylimidazolium Bis((Trifluoromethyl)Sulfonyl)Imide usually turns up in labs and industries hunting for alternatives to toxic solvents. In my experience working with chemicals meant for cleaner technologies, people see this class of ionic liquids as less volatile, less likely to catch fire, and simpler to handle than classic solvents like benzene or acetone. These perks make it attractive for batteries, chemical synthesis, and even electroplating.

Hazards Hiding in Plain Sight

Even if something doesn’t blow up or evaporate into a toxic fog, it can still spell trouble. Just because this compound gets tagged as an “ionic liquid” or “green solvent,” people might dismiss concerns. Safety depends on more than just boiling points and chemical trends. In practice, questions about toxicity keep coming up when labs bring in new materials.

Touching, breathing in, or swallowing unknown chemicals opens the door to nasty surprises. N-Methylimidazolium derivatives are no exception. Animal test data for closely related imidazolium-based ionic liquids often flag irritation and injury when in contact with skin or eyes. Some studies show these substances cling to biological tissues, sometimes messing with liver enzymes or cell membranes. My background in chemical handling tells me that gloves and goggles aren’t optional—these are the basics, not window dressing.

Long-term effects of chronic exposure aren’t mapped out for every variant, and that goes double for N-Methylimidazolium Bis((Trifluoromethyl)Sulfonyl)Imide. The fluorinated "bis" part adds another layer. Compounds with strong carbon-fluorine bonds break down slowly, if at all. Perfluorinated chemicals in other settings have built up a bad reputation for sticking around in soil, water, and living things. Even companies that set up ionic liquid processes sometimes treat spent solutions as hazardous waste because of these persistence risks.

Environmental Footprint Matters

No one has concrete data for every last ionic liquid, but trends point to trouble if lots of this stuff escapes the lab or factory floor. Small leaks add up over years, ending up in wastewater. Sewage treatment struggles to filter out long-lived, fluorine-heavy substances. My own time spent inspecting spill response drills convinced me that early and honest risk assessment beats trying to clean up after the fact. It’s cheaper, too.

So, What Should Happen Next?

People should treat N-Methylimidazolium Bis((Trifluoromethyl)Sulfonyl)Imide with due caution. Reliable gloves, splash goggles, and chemical fume hoods support a safer workplace. Spill kits and clear storage labels are just as important. Accurate material safety data sheets should travel with these bottles, not get lost in a pile of paperwork.

Regulators, scientists, and industry need to dig deeper into how this ionic liquid behaves in real-world conditions. Standard chemical screening tests won’t cover everything. Partnerships between academia and manufacturers can produce better toxicological profiles, so it’s not just guesswork. Efforts to develop safer versions—less persistent and less bioaccumulative—would shrink risks if this trend toward ionic liquids keeps rolling.

New technology needs realism more than hype. For now, treat “greener” solvents with a dose of respect, not complacency. Using experience and trusted data as guides, the smart approach means erring on the side of caution, not just best-case scenarios.

Pushing Past the Hype of High Numbers

You see “99% purity” shouted from the labels of many products. Some folks hear that and figure, great—nearly perfect. Step back and think about all the things that 1% can actually represent. That small leftover might include everything from harmless extra salts to things no one would want in their food, supplement, or lab materials. For example, pharmaceutical-grade sodium chloride clocks in at 99.9% or higher, and even that last little bit gets scrutinized under strict guidelines. Purity isn’t just about big numbers, it’s about what that other stuff is. After seeing some low-cost vitamin brands cut corners, I always check those extra decimals and demand a Certificate of Analysis.

The Role of Regulations and Real-World Testing

No two jars of “the same” compound are truly identical. Different countries draw different lines for what they accept. American or European pharmacopoeias usually want 99.0% or above for lab chemicals, especially anything involved in studies or medicine. Food ingredients often don’t require such gold standards, but the best suppliers still put their powder or liquid through high-performance liquid chromatography. I toured a supplement factory once—those folks tested basically every drum against a set list of impurities. It’s not the label that earned trust, but the evidence in the paperwork.

Where Lower Purity Slips In

Industrial and agricultural sectors often make do with lower purities: you might see 95% or even less if the product just acts as a fertilizer or goes into concrete. The stakes rise once that product touches our skin or goes into our mouth. Regulatory agencies keep a close eye on what nasties could sneak in with each impurity: banned heavy metals, allergens, or rogue bacteria. I once helped a friend trace a weird rash to trace contaminants in a “natural” essential oil. Cost sometimes pushes companies to loosen standards, so savvy buyers know cheaper goods can bring more hidden risks.

Trouble Brews When Purity Isn’t Prioritized

Think of famous product recalls—tainted heparin in 2008, baby formula scandals, supplement contamination reports. Each story shows purity isn’t just a technical stat. A few extra points on the purity score can save lives, especially with medicines or infant foods. The FDA and other watchdogs run random tests for good reason. People trust that the fancy percentage means the company stood behind their process and checked for the worst possibilities—not just the easy-to-measure ones.

Demanding More Transparency and Better Habits

Average people don’t always ask for specs or independent testing, but we all could stand to push for it. Anyone buying food additives, supplements, or ingredients for their business should look for batch analysis, third-party audits, and a supplier who answers questions without dodging or giving vague answers. If suppliers had to publish contaminant limits and batch numbers the way craft breweries list hops, maybe all of us would sleep easier. Higher purity might not guarantee perfection, but it nearly always means less risk and fewer unwanted surprises on a bad day. Standards matter, but real peace of mind needs both the number and the story behind that number.

Understanding the Risks in Everyday Terms

N-Methylimidazolium Bis((Trifluoromethyl)Sulfonyl)Imide, or [BMIM][TFSI] if you go by its common shorthand, keeps showing up in labs that push into battery technology, electrolytes, or green chemistry. It’s easy to see why chemists like it. It doesn’t evaporate at room temperature, it helps boost ionic conductivity, and it dissolves all sorts of stuff. But this same chemical can cause headaches—maybe more—if handled sloppily.

Safety isn’t just a classroom lecture about risk assessments. Every bottle in the chemical store brings some danger. [BMIM][TFSI] falls in that camp since the trifluoromethyl and sulfonyl groups throw in environmental questions, while its imidazolium base can irritate eyes or skin. One slip-up during preparation or cleanup, and somebody could get exposed or worse, send it down the drain.

Practical Handling: Gloves, Goggles, and Good Sense

Respect for safe handling always starts with reliable gloves—nitrile or better. Splashing, even a drop, means a serious eye irritant. Standard laboratory goggles do more than tick boxes. They keep accidents from turning into ER visits. Lab coats won’t just keep your clothes clean—they matter for protecting skin from splash as well.

Ventilation deserves just as much attention. If you pour or mix this stuff, use a chemical fume hood. Heavy use in a closed-up room leads to air quality problems fast. Good habits in the lab stack up over time, reducing small exposures that people barely notice, but can trigger headaches or allergic responses after years on the job.

Storage Means More than a Label

Anybody who has managed a chemical cabinet knows what warm, damp air does to sensitive compounds. [BMIM][TFSI] prefers a dry, cool spot, tightly capped. Humidity will mess with its purity, so keep it dry. Double-contain bottles if possible, especially if sitting near acids or bases. A leak next to an incompatible chemical can ramp up risks, including fire.

The Realities of Disposal

Disposal gets tricky. You can’t dump ionic liquids or their solutions down the drain. Not only will that run afoul of safety and environmental standards, but sewer systems can't remove persistent fluorinated compounds. These days, responsible labs collect used ionic liquids in labeled, sealable containers for hazardous waste pickup. It’s more paperwork, but makes all the difference for downstream water and wildlife.

Experience says small labs sometimes short-circuit this process, especially as wastestreams get crowded or budgets get tight. But agencies like the EPA haven’t stopped watching—violations catch up eventually. Safe disposal turns into good science stewardship.

Facts, Not Overpromises

Ionic liquids keep powering up research, but people and ecosystems absorb the bill when shortcuts happen. The American Chemical Society, National Institutes of Health, and local hazardous waste teams all publish best practices. Every lab member, from PI down to undergrad, should spend time with these guides.

Working with new chemicals means treating every step—handling, storage, and disposal—with attention and training. It’s not just about ticking safety boxes; it’s about keeping progress from turning toxic. With proper respect, everyone goes home safe, and research keeps moving ahead, not backward.