Octadecyldimethylbenzylammonium Chloride: From Early Discovery to Modern Innovation

Historical Development

Scientists first introduced quaternary ammonium compounds in the early 20th century, looking for effective disinfectants to answer widespread public health problems. Octadecyldimethylbenzylammonium chloride stands as a result of that search. During the 1940s, hospitals and industrial circles prioritized strong antimicrobial products, which put this quaternary ammonium compound on the map because of its persistence on surfaces and broad microbial killing power. Companies and public health agencies have since relied on this family of chemicals for everything from controlling pandemics to sanitizing food-processing plants. Over decades, new forms and derivatives arose, but octadecyldimethylbenzylammonium chloride kept its seat in disinfection toolkits because of its proven track record.

Product Overview

This compound appears as a white to off-white powder or solid, dissolves well in alcohol and water, and carries a faint odor that most people can barely detect. Manufacturers often ship it as a concentrated solution and expect users to dilute before use. You’ll find variants with different chain lengths or substitutions, but the bulk of the business runs on the C18 chain version for its balance of antimicrobial strength and physical stability. Broad use across public, agricultural, and private sectors supports robust global demand, which keeps prices relatively stable year after year, even as regulations and standards become stricter.

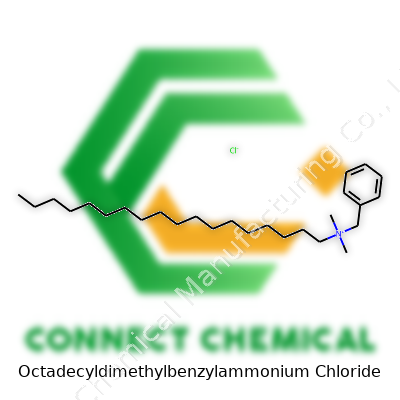

Physical and Chemical Properties

Octadecyldimethylbenzylammonium chloride features a long hydrocarbon chain tied to a benzyl ring and a quaternary ammonium head. This setup makes the molecule surface-active, gathering at interfaces between oil and water, which helps dislodge dirt and break up microbial cell membranes. Its melting point sits around 60-70°C, and it dissolves well in polar solvents. The product’s cationic nature encourages it to stick to negatively charged surfaces like glass, cotton, or skin, which means less product gets washed away during rinsing compared to older, anionic soaps. The compound resists breakdown under dry or cool storage but will slowly hydrolyze in heat or strong acid, which explains why the industry stresses proper storage protocols.

Technical Specifications and Labeling

Each batch comes with a guaranteed purity level—usually at least 98% for industrial or pharmaceutical uses. Manufacturers list impurities, moisture content, pH of a 1% solution, and presence of free amine, since those factors can interfere with antimicrobial action or create side reactions in sensitive applications. Bulk containers require clear hazard and handling symbols due to caustic and irritant features. International shipping tags rely on harmonized codes and the GHS labeling system so customs and users know to keep the product away from skin, eyes, or incompatible chemicals like nitrates or strong oxidizers.

Preparation Method

Commercial suppliers normally start with stearyl chloride and react it with dimethylbenzylamine under controlled temperature in a sealed vessel. This quarternization reaction proceeds quickly in water or alcohol, as long as you keep the reaction mixture free from contamination or excess humidity. Once finished, technicians filter off by-products, strip unwanted solvents, and refine the remaining solid through recrystallization or activated carbon treatment. The process takes skill because any leftover reactants sap product quality or yield, so reputable vendors run frequent batch tests to flag off-standard shipments. Responsible plants also recycle or treat their waste residues, since improper disposal damages both company reputation and water quality in local communities.

Chemical Reactions and Modifications

This molecule resists hydrolysis in mild conditions but reacts with strong bases or oxidizers, splitting the chain or knocking off the benzyl group. Chemists sometimes tweak the hydrocarbon tail for specialty uses—for instance, shortening it for better cold-weather solubility or adding bulky groups for hospital-use wipes needing slower evaporation rates. In biocidal blends, formulators avoid mixing it with anionic surfactants, since the two neutralize each other at the molecular level. Current research pays close attention to how modified analogues work against viral coats or break up protein matrices, hoping to optimize cleaning efficiency without boosting toxicity for aquatic species downstream.

Synonyms and Product Names

Suppliers recognize this chemical under a host of alternative terms such as "stearyl dimethyl benzyl ammonium chloride," "C18 benzalkonium chloride," or "stearyl quaternary ammonium salt." Patented formulations attach their own trade names, promising specialized release profiles or combined action with other surface-active agents. Lab catalogs and import papers still rely on unique registry numbers to prevent identity slips or mislabeling, especially as more regions enforce strict customs controls over biocidal imports and exports.

Safety and Operational Standards

Long experience handling industrial quaternary ammonium compounds has built a layered safety culture. Warehouse and facility workers need splash goggles, chemical gloves, and tight containers with clear signage to cut down on skin and eye injuries. Emergency flushing stations show up wherever the compound gets handled or mixed, since even diluted solutions can burn mucous membranes. Because the molecule stays active at very low concentrations, waste streams and rinsate water go through treatment plants or settling ponds to avoid accidental release into rivers or lakes. Governments update safety datasheets based on real-world spill reports, so staying current with new safety rules acts both as self-protection and as a mark of responsible stewardship.

Application Area

Custodians in schools, hospitals, and public transit rely on octadecyldimethylbenzylammonium chloride to wipe down furniture, doors, and bathroom fixtures, knocking out bacteria, fungi, and enveloped viruses. Livestock farmers treat cattle pens or hatcheries, trying to limit outbreaks without using harsh, bleach-based sanitizers that degrade quickly in sunlight or damage rubber. Textile processors use it to give fibers antistatic, moth-resistant, or mildew-inhibiting finishes. Some paint makers add small amounts for mildew-resistance in humid bathrooms or kitchens, and water treatment plants tap into its flocculant power to separate oily waste or kill off harmful algal blooms. Products as humble as mouthwash or floor wax build part of their appeal around “hospital grade” claims, thanks in no small part to this dependable quaternary compound.

Research and Development

Drug discovery teams and environmental engineers study octadecyldimethylbenzylammonium chloride, looking for gaps and opportunities. For instance, labs test new analogs with altered alkyl chains, hunting for antimicrobial action with less aquatic toxicity. Wastewater researchers run pilot filters trying to catch trace residues, hoping to keep rivers and aquifers clean downstream from large disinfection plants. Product engineers mix compounds for continuous-release coatings, aiming for surfaces that destroy germs for days rather than giving up at the first wet wipe. Safety experts watch microbial resistance trends, studying how overuse might shift populations of tolerant bacteria, then recommend shorter rotation cycles or different combinations in sensitive wards.

Toxicity Research

Laboratory tests show octadecyldimethylbenzylammonium chloride irritates skin, eyes, and respiratory linings in concentrated form. Chronic overexposure can delay wound healing and provoke rashes, so labels on retail sprays and wipes highlight both dosage and rinse instructions. Environmental toxicity looms larger as more residues reach rivers and lakes. Aquatic species like daphnia and fish react at parts-per-million levels, and repeated exposure disrupts bacterial communities in soil and water. Scientists weigh the benefits of strong household cleanliness against risks to downstream wildlife, and public agencies run risk assessments to limit allowable concentrations in treated water leaving city plants. Responsible reformulation and tighter waste disposal rules address both short-term worker safety and long-term water health.

Future Prospects

Global demand for disinfectant solutions rises along with population density, climate change-driven disease risk, and tighter public health codes. Researchers evaluate whether tweaks to molecule structure can reduce aquatic toxicity or slow resistance development, using data from new DNA sequencing and environmental sampling technologies. Startups develop biodegradable analogs, hoping to keep killing germs without overloading rivers or farm fields. Governments and environmental bodies draft ever-stricter regulations, pushing producers to list exact concentrations and ingredients in consumer products. Companies able to demonstrate lower environmental burden stand to grab new contracts, especially in regions tightening chemical import standards. Expanding research investment promises new blends for agriculture, food safety, and long-life surface sanitizers, but success rides on making products safer for both people and nature. Personal and community health, industrial innovation, and environmental stewardship converge in this ongoing evolution of an old but still important chemical.

The Science of Staying Clean

I walk into a hospital or school and know that people have scrubbed, sprayed, and wiped every surface I see. A lot of the time, chemicals like octadecyldimethylbenzylammonium chloride do the heavy lifting. This compound sounds like something a chemist invented just to trip us up. In reality, it works day in and day out, keeping bacteria, mold, and viruses on the run.

Disinfecting in Healthcare

In a medical environment, invisible threats hang around on surgical tools, bed rails, and floors. A huge number of surface disinfection products list quaternary ammonium compounds as their main ingredient. Octadecyldimethylbenzylammonium chloride belongs in this group. It breaks down the cell walls of germs fast, stops them from multiplying, and has made itself part of everyday infection control. Studies from the CDC show hospitals that train cleaning crews to use "quats" like this one see lower rates of hospital-acquired infections.

Cleaners and Sanitizers in Daily Life

Everyday folks use this stuff, too. Walk into almost any public building—schools, offices, gyms—and you’ll spot wet wipes or sprays designed to quickly kill surface germs. Home cleaning brands have turned to this ingredient for everything from kitchen counters to bathroom tile. Food processing plants and restaurants also trust the compound to keep workspaces free from Salmonella and E. coli. If food comes into contact with a surface treated with this chemical, low residue means less concern compared to bleach.

Public Safety and Transport

People ride buses, touch handrails, push elevator buttons. Shared surfaces can spread colds, the flu, and worse. Transit authorities increasingly spray down spaces with products containing octadecyldimethylbenzylammonium chloride. I’ve seen daily deep cleans on subways since the COVID-19 pandemic, and this ingredient rarely misses an appearance in the sanitizer blends. Research from the National Institutes of Health highlights that regular disinfecting of high-contact spaces cuts viral transmissions by large margins.

Drawbacks and What Needs Attention

Chemicals that kill microbes don’t stop with bacteria—they can harm aquatic life if flushed down the drain. Some people find their skin irritated after repeated contact. Too much reliance on quats can also let resistant strains pop up, just like overused antibiotics. Responsible users keep this in mind. That doesn’t mean throwing out disinfectants, but it does call for education. Using protective gloves, letting surfaces dry fully, and never mixing these with other cleaners are basic steps that help.

Looking at the Road Ahead

The cleaning industry continues to look for greener, smarter blends that still knock out germs. Some schools and hospitals now alternate cleaning agents to slow down resistance. Others train staff to measure and apply exact amounts, which stops waste and environmental overflow. Research keeps rolling on new formulas, but for now, octadecyldimethylbenzylammonium chloride stands as a frontline defender in keeping spaces safe.

The Real Story Behind a Common Cleaner

Walk through almost any cleaning aisle and you spot labels filled with long chemical names. Octadecyldimethylbenzylammonium chloride is one such mouthful. Most people know it through its nickname – quats – in their favorite disinfectant sprays, wipes, and surface cleaners. The stuff works by smashing apart cell membranes in bacteria and some viruses, making it a go-to ingredient in the fight against germs.

Exposure at Home: What Science Says

Nobody wants their kitchen and bathroom harboring dangerous bugs. But using strong disinfectants around the house always brings up the question: what else are we spreading around? Scientific studies show that quats can cause mild skin or eye irritation in certain folks, especially when used without gloves. Prolonged or frequent contact, like during daily cleaning, can dry out skin or cause redness. Children and pets can sometimes be more sensitive, since they may crawl or play on floors and surfaces that got a heavy spritz.

Research on animals finds quats can sometimes cause mild breathing irritation if inhaled in large amounts, such as with a mist or spray in a tight space. Humidifiers once used them, but reports of lung problems in kids and pets led many makers to switch formulas. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) sets strict rules for how these chemicals enter the home, including labeling, concentration limits, and how products must be used so that risk stays low. That matters: my own pets used to hang around while I cleaned, but I learned fast to keep them out of freshly cleaned rooms until surfaces dried.

Impact on Pets and Children

Dogs, cats, and even birds show unexpected sensitivity to many household cleaners. Cats will lick just about anything. Dogs eat crumbs straight from the floor. Unlike adults, kids rub their faces, crawl, then stick fingers into their mouths. Dermal exposure and accidental swallowing become real concerns. Poison control centers list dozens of calls every year about chemical cleaners, some leading to vomiting, drooling, and worse. Not just from guzzling the bottle—sometimes even licking a damp spot or licking paws after walking on a freshly cleaned floor is enough to cause mild poisoning.

Some veterinary journals highlight that quats haven’t been studied as deeply in pets as in people, but cases of mild gastrointestinal distress do show up. My local vet has handed out leaflets reminding folks to lock away all cleaners, not just the obvious ones.

Good Habits for Cleaning Safely

Store cleaning products on high shelves and use child- or pet-proof locks. Always read the fine print on the label and mix cleaners only as instructed—mixing chemicals such as these with bleach or acids can release toxic fumes. Wear gloves if your skin dries out easily. Wipe away excess solution, then allow surfaces to air dry before letting anyone touch or walk on them. Open a window or turn on a fan while you clean.

Plant-based cleaners or plain soap and water do the trick in many cases, saving quats-based products for deeper, occasional disinfecting. If someone in the house has asthma or sensitive skin, look for options without strong chemical disinfectants.

Using science-backed information, paying attention to product labels, and building safer habits can protect families and pets from unnecessary risk, without giving up a clean, healthy home.

Understanding Chemical Safety

Octadecyldimethylbenzylammonium chloride pops up often in hospitals, labs, and cleaning supply closets thanks to its antimicrobial power. It kills germs well, but it’s still a chemical that brings along some safety responsibility. Years of working around powerful disinfectants have taught me that the difference between safe and risky comes down to habits, not luck.

The Role of Temperature and Moisture

Heat and humidity speed up chemical changes, so keeping this compound in a cool, dry spot protects its strength and user safety. Basements with leaky pipes or stuffy rooms with broken AC don't cut it. I've seen what a muggy storeroom does—sticky containers, drippy rings on the shelves, and labels curling up. Under those conditions, chemicals like this one break down, packaging weakens, and the risk for leaks climbs.

Rooms meant for chemicals usually have temperature control—think low humidity and out of direct sunlight. Refrigeration isn’t necessary, just avoid keeping it anywhere above typical room temperature. Some colleagues used to stash extra cleaning chemicals in a closet near the furnace room to 'save space.' Instead, that space nearly baked the bottles. Cool storage matters.

Container Choice and Labeling

By law and logic, original packaging protects both the product and the people working with it. The original container’s seal keeps out air and damp. If the label peels off, confusion grows. Nobody wants a 'mystery jug' in a chemical stash. On a hospital cleaning crew, I saw unused quats poured into soda bottles more than once. Accidents followed. Clear labeling, no cross-contamination, and no improvising containers—these aren’t rules just for rules’ sake; they prevent dangerous mistakes.

Separation from Incompatibles

Mixing chemicals has never turned out well in my experience. Octadecyldimethylbenzylammonium chloride doesn’t get along with oxidizers or acids. Splashing or leaking from neighboring bottles causes problems fast. Shelving that keeps incompatible chemicals apart works better. Open bins for random bottles let spills mix instantly, which I’ve learned the hard way.

Accessibility and Security

Locked storage keeps the workplace safe. I’ve seen kids wander into unlocked storage rooms in community centers; one time, a child tipped over a cleaner bottle and suffered burns. Access only for trained staff—no exceptions. Store the chemical below eye level and away from food items. Stacking limited amounts on shelves marked clearly for “dangerous chemicals” makes a real difference.

Ventilation and Emergency Prep

Poor airflow in storage areas lets fumes build up. A chemical room with a vent fan that runs every hour has always felt safer to me. If there’s a spill, a nearby eyewash station and a written emergency chart cut down panic time. For small workplaces, even placing water and gloves nearby can help until professional responders arrive.

Simple Practices, Serious Results

Safe chemical storage shapes workplace trust. Every clear label, every trip to the trash with old containers, and every quick mop of a spill matter. By focusing on everyday habits—proper temperature, strong labeling, sealed lids, secure access—people protect both themselves and those around them. Mistakes shrink and confidence grows each time someone opens that chemical cupboard, sure that what’s inside has been stored right.

Why Dilution Matters

People hear a mouthful like octadecyldimethylbenzylammonium chloride and think science fiction, but it’s a common disinfectant that keeps workspaces, hospitals, and homes safer. The punch it packs against germs depends a lot on how it’s mixed. Too little and harmful microbes survive. Too much and surfaces grow sticky or unsafe for humans and animals. I’ve used quaternary ammonium compounds on jobs in food service and facility maintenance, and slack dosing kills trust as much as germs.

Suggested Dilution Ratios

Common products mix this chemical at concentrations between 200 and 400 parts per million (ppm) for regular surface cleaning – about 1:256 or half an ounce per gallon of water. This guideline matches what health authorities like the CDC and EPA advise for controlling harmful bacteria and viruses. Higher concentrations, up to 800 ppm, serve for hospital floors after blood spills or high-contamination cases, under close supervision.

These numbers are not just for lab coats. If you go too strong, surfaces can end up sticky, and residue builds up. If you go too light, surfaces remain contaminated. I’ve seen both outcomes in real kitchens and patient rooms. Cleaning crew leaders worth their salt measure out solutions carefully, using a test strip or titration kit.

Personal Safety Counts

As with any chemical that's tough on germs, personal safety takes top priority. Always use waterproof gloves—broken skin and harsh disinfectants don’t mix. Good ventilation keeps chemical fumes from building up in closed rooms. Eye protection matters, especially around atomized sprays or if you’re pouring concentrate. Every mentor I had in building maintenance drilled that home. Over the years, I’ve seen folks ignore those steps and pay for it with dry, cracked hands and irritated noses.

Proper Application Methods

Pouring diluted disinfectant onto a rag and wiping surfaces in a clear pattern works for tables and counters. With floor cleaning, mops or auto-scrubbers distribute the solution. It’s important not to mop yourself into a corner. Spray bottles are handy for small fixtures and shared equipment, but you want to avoid spraying near electronics or uncovered food.

Letting surfaces stay visibly wet for the product’s contact time—usually anywhere from 5 to 10 minutes—finishes the job. Rushing this step just wastes product and effort. On my old routes, managers checked for compliance with a simple timer. This routine, more than the brand name on the bottle, kept illness from spreading in my experience.

Improving Daily Practices

The best solutions use color-coded bottles and measuring tools as part of daily culture. Clear instructions posted above dilution stations leave less to chance. Training new workers hands-on with test strips, rather than handing out printed instructions, builds real confidence. Early in my career, I saw how these tight habits stopped cross-contamination in its tracks.

Some issues still crop up when workers skip steps to save time—shortcuts don’t work. Better training and spot-checks can fix most slips. Leadership that walks the walk, showing up for occasional deep cleans, sends a stronger message than just memos ever could.

What’s at Stake

This compound is a useful tool, but it’s not magic. Community health improves most with careful use, routine checks, and practical training. People working with it need to respect its strength by using accurate measurements and protective equipment every single time.

Understanding What’s in That Disinfectant Bottle

Octadecyldimethylbenzylammonium chloride shows up under trade names like “quats” in hospital wipes, sprays at the gym, and sometimes in household cleaners. Consumers trust these products to kill germs. Yet, safety fades into the background in the rush to clean surfaces. My experience working at a science museum involved plenty of time with cleaning agents. After seeing colleagues react to a variety of disinfectants, I started reading more about what actually goes into them.

Breathing Isn’t Always Easy

Let’s get real—breathing in fumes from quats is no pleasant experience. According to studies published by the CDC and OSHA, inhaling the mist can irritate lungs, nose, and throat. I’ve watched coworkers develop watery eyes and scratchy throats after spraying down tables with quat-based products. Prolonged exposure? Reports suggest asthma and other respiratory symptoms can creep up, especially for custodians and daycare staff constantly reaching for disinfectants.

Skin Contact Is No Joke

My hands have turned red and chapped more than once after using wipes soaked in octadecyldimethylbenzylammonium chloride. The product can cause dermatitis—fancy way to say “your skin flares up and itches.” Gloves help, but not everyone remembers to grab some rushing between tasks. Long-term contact ramps up the risk, too, based on cases reported among healthcare workers.

Accidental Swallowing Isn’t Unheard Of

Kids get into everything. It’s easy to picture a child picking up a just-cleaned toy and putting it straight into their mouth. Poison control centers warn that ingestion can lead to nausea, vomiting, and burns in the throat. The bright packaging on some wipes looks harmless, but it’s not. Hospitals treat accidental poisonings every year, and the numbers aren’t small.

Environmental Impact Deserves a Closer Look

Quats like this one don’t just vanish after soaking into rags or swirling down drains. Research by the USGS points to residues collecting in waterways, showing up in sediments and sometimes entering food chains. Aquatic life reacts badly—even low levels have been tied to problems in fish and invertebrates. Local communities downstream from big laundries and hospitals face bigger consequences than many realize.

What Makes Common Sense With Quats?

Wearing gloves and working in well-ventilated spaces matters. Overusing any chemical cleaner makes no sense—surface grime isn’t always a threat, and overdisinfecting means unnecessary exposure. Read the label, use the smallest effective amount, and give cleaned surfaces time to dry before touching. If sharing spaces with kids, keep bottles and wipes locked away.

Looking Toward Cleaner Solutions

Alternatives are catching on. Plain soap and water work for everyday cleaning in many cases. For those who want disinfection, products carrying EPA “Safer Choice” labels signal lower risks. Green cleaning teams in schools and offices show it’s possible to cut hazardous exposures without slacking on hygiene. Pushing manufacturers to list ingredients in plain English would help everyone make informed choices.

Everyone Deserves Safe Spaces

Cleaning shouldn’t come with invisible hazards. Octadecyldimethylbenzylammonium chloride kills germs, but too often at a cost to those using it most. Workers, families, and communities can all push for safer use, clearer guidance, and real alternatives. A bottle of cleaner shouldn’t make life harder when the goal is keeping everyone safe.