Octyltrimethylammonium Bromide: Beyond the Laboratory Bench

Historical Development

Chemists in the mid-20th century began to explore new ways to coax water and oil into mixing, not just for kitchen emulsions but to tackle challenges in industry and research. Amid this work, the quaternary ammonium compound family grew. Octyltrimethylammonium bromide showed promise as an effective surfactant, thanks to its unique alkyl chain structure that started showing up in practical applications by the 1960s. At the time, advances in phase-transfer catalysis also helped to push its adoption. Chemists found that by adding a chemical like this, they could bridge the stubborn gap between water-soluble and oil-soluble substances, speeding up and enhancing chemical reactions that previously dragged on or required harsh conditions. Tracing this compound’s commercial development, you’ll spot a direct line between the growth of organic synthesis and the rise of surfactants willing to ‘do the dirty work’ between phases.

Product Overview

Octyltrimethylammonium bromide sits among the more accessible quaternary ammonium compounds, affectionately known in some circles as OTAB or OTMA-Br. It comes as a white to off-white powder or crystalline solid, dissolving easily in water and alcohol—turning even a stubborn phase boundary into a manageable interface. Manufacturers tout its value for boosting reaction rates, stabilizing dispersions, and improving the throughput of chemical processes where traditional surfactants fall short. Whether a student in an underfunded classroom or a seasoned chemist managing a pharmaceutical plant, the compound’s versatility and reliability attract plenty of attention.

Physical & Chemical Properties

Octyltrimethylammonium bromide stacks up with a molecular formula of C11H26BrN and a molar mass near 252.24 g/mol. Its melting point lands at about 237°C, but under real-world storage, it handles fluctuation with little fuss—so long as humidity stays low. Solubility in water, ethanol, and hot methanol makes it a faithful partner in complex mixtures. The compound owes its amphiphilic nature to the octyl group’s hydrophobic tail and the charged ammonium head—giving it that signature surfactant behavior. In practical terms, this means it can wrap organic molecules in an aqueous solution or pull water-dwelling ions into organic solvents with ease.

Technical Specifications & Labeling

Quality standards from leading chemical suppliers suggest a purity above 98%, with clear labeling for lot numbers and manufacturing dates. Regulatory compliance, including GHS labels for handling and transport, can’t go overlooked—users expect hazard statements, precautionary advice, and specifics on storage conditions. Popular suppliers run both batch-to-batch content verification and document every analytical result, so chemists and engineers get what the label promises every time. Incorrect or incomplete labeling can backfire quickly, endangering workers or blunting process performance, so manufacturers compete to earn trust here with certifications and traceability.

Preparation Method

Producers usually lean on a quaternization reaction between trimethylamine and 1-bromooctane. The process runs under mild heat and controlled pH, using solvents like ethanol or acetonitrile to keep things moving. Operators must maintain tight control of reaction stoichiometry and time—run it too short, and you’re left with reactants that didn’t get the memo; run it too long, and impurities creep in. After reaction, washing and recrystallization weed out byproducts. One of the most memorable lessons from my time in a teaching lab: students who rushed recrystallization saw cloudy products and poor performance, while careful, patient work paid off with gleaming crystals ready for any challenge.

Chemical Reactions & Modifications

With that exposed ammonium head and hydrophobic tail, octyltrimethylammonium bromide behaves like a chaperone for charged molecules in organic phases. It stands out in phase-transfer catalysis, ferrying reactants across immiscible barriers so reactions hit their target. Under basic conditions, it won’t decompose, but strong acids, oxidizers, or prolonged heating can break it down. Chemists sometimes tweak the tail group—swapping octyl for other alkyl chains—to fine-tune solubility or interaction strengths for particular applications. Each modification shifts behavior, so research continues into variations that improve selectivity or handling under tough conditions.

Synonyms & Product Names

Depending on the supplier, octyltrimethylammonium bromide shows up as OTAB, OTMA-Br, or simply octyltrimethylammonium bromide. Academic papers and patents often use these terms interchangeably, creating confusion if users don’t check CAS numbers or product codes. The lesson: always check the fine print on your supplier’s certificate of analysis before starting an experiment or production run to avoid mismatches or costly setbacks.

Safety & Operational Standards

Direct contact with octyltrimethylammonium bromide can irritate skin, eyes, and respiratory tracts. Anyone handling the powder in lab or plant settings wears gloves, goggles, and respirators as needed. Safety training drills the importance of sealed containers, airtight storage, and labeled workspaces—leaks or spills create hazards that stretch beyond a single bench, given this compound’s persistence in the environment. Spill kits with absorbents stand ready, and waste gets collected according to hazardous material guidelines. Workplace rules often reflect learning from hard lessons—protect each other, double-check labels, and keep a clear protocol in place even during overtime hours.

Application Area

Industries turn to octyltrimethylammonium bromide for far more than its scientific cachet. Water treatment plants depend on it to clear up oils and organic dyes from wastewater, relying on the compound’s knack for pulling grease out of a stubborn emulsion. Pharmaceutical research labs find it indispensable for phase-transfer catalysis, especially where sensitive molecules won’t survive harsh conditions. Even in cosmetics, OTAB stabilizes formulations and helps active ingredients penetrate where they can do the most good. Researchers keep pushing into new applications, expanding possibilities in nanotechnology, antimicrobial coatings, electronics, and green synthesis routes. Each new success story traces back to OTAB’s ability to bridge different chemical worlds.

Research & Development

Academic teams and private-sector labs continue to experiment with octyltrimethylammonium bromide to overcome roadblocks in synthesis and materials science. A major theme shows up again and again: reducing solvent consumption and energy use while increasing yield. Research into surfactant recycling, selective catalysis, and controlled-release drug delivery leans heavily on this compound’s adaptable profile. Major grants support work into hybrid materials, while feedback from real-world operations feeds a loop of improvement—making sure each iteration delivers more value and fewer environmental headaches. Communities that support open sharing of procedures and results speed the pace of innovation, showing the value in collaboration alongside competition.

Toxicity Research

Safety committees and regulatory agencies demand thorough investigation into any chemical used on a large scale, and octyltrimethylammonium bromide is no exception. Peer-reviewed studies report moderate toxicity for aquatic species, raising flags about unchecked disposal into waterways. In mammals, toxicity levels run low to moderate, but repeated exposure in high concentrations calls for care. Years ago in one academic project, I saw firsthand how even low-toxicity surfactants unsettle biological test systems—planning disposal and monitoring use isn’t an afterthought, but a baseline responsibility. Agencies recommend strict limits for occupational exposure, while researchers keep exploring greener alternatives or improved formulas with lower impact.

Future Prospects

Industrial and academic momentum points toward a bright, though closely scrutinized, future for octyltrimethylammonium bromide. Manufacturing improvements focus on greener synthesis routes, starting with renewable feedstocks and factory designs that cut emissions and waste. User demand for more effective, less hazardous surfactants drives ongoing tweaks to structure, purity, and partner chemicals. Regulations and consumer pressure push companies to address toxicity concerns, adopt closed-loop processing, and invest in continuous safety upgrades. If the past half-century offers any lesson, it’s that compounds like OTAB won’t disappear—rather, their evolution is tied directly to how scientists, engineers, and regulators learn from each challenge and build solutions that blend practicality with environmental and human health.

A Closer Look at Its Role in Chemistry and Industry

Octyltrimethylammonium bromide steps into the picture as a specialty chemical with several hats. In the lab, this compound helps chemists push boundaries in separations, analysis, and even drug delivery. Its main feature is the long octyl chain sticking out from the ammonium core—this tail lets the molecule act like a traffic controller for other substances: one end loves water, the other hates it. With this personality, it’s a textbook example of a surfactant, a substance that can help keep oil and water together—or apart—depending on what the job demands.

Essential in Making Separations Work

My first memories of octyltrimethylammonium bromide, or OTAB, come from my time in a university chemistry lab. I saw it as a helper for liquid-liquid extractions. Pulling out one compound from a messy mixture isn’t just about luck—it’s about coaxing molecules to choose sides. OTAB forms “micelles,” tiny clusters that grab hold of oily substances floating in water. This trick helps scientists purify products, analyze environmental samples, and even test medicines. According to a study in the Journal of Chromatography A, surfactants like OTAB can boost sensitivity in chromatography, making it easier to spot low levels of pesticides and pollutants. In environmental science, every percent of improvement in detection can turn a foggy water safety report into a clear warning.

OTAB as a Phase Transfer Catalyst

Dive deep into industrial chemistry, and OTAB takes on another role. It smooths the path for chemical reactions where the pieces won’t play nicely in the same solution. Let’s say an oil-based reactant and a water-soluble partner need to come together. OTAB sits between them, pulling one closer to the other. On a practical level, this opens doors to safer, faster, and less wasteful chemical making. The value comes in pharmaceuticals and specialty materials, where clean reactions mean fewer headaches down the line. Citing research from Green Chemistry, using phase transfer catalysts like OTAB slashes energy and solvent needs in chemical plants, ticking boxes for both profit and the planet.

Influence on Drug Delivery and Nanotechnology

Doctors, pharmacists, and patients rarely hear the name, but OTAB shows up behind the scenes in medicine. In drug delivery research, scientists build nanostructures to carry medicine to the right spot. The structure needs to hold together until it reaches its target, and OTAB helps by forming small capsules or vesicles. Studies in Colloids and Surfaces B: Biointerfaces show that surfactants like OTAB help create stable particles, giving life to new ways of treating cancer or infections. With diseases like cancer, the stakes don’t get much higher, so every advance in delivery counts.

Is OTAB Safe? Addressing Health and Environment

Any chemical with this much reach brings questions. Safety comes up everywhere OTAB is used. It doesn’t show up in household products or foods, but anyone working with it should handle it thoughtfully. According to the European Chemicals Agency, OTAB can irritate skin and eyes, so gloves and goggles are smart protection. Environmental risks remain; persistent surfactants can build up and affect water life. Regulators and companies need monitoring and better waste practices—win for everyone if chemical benefits don’t come at a hidden environmental cost.

Moving Forward: Greener Chemistry

Scientists keep searching for ways to make useful tools less risky. OTAB brings value, but the next step involves either recycling it more efficiently or designing chemicals that do the same job with a lighter footprint. Investment in greener alternatives comes slow, but real progress stacks up when researchers, companies, and regulators work in the same direction.

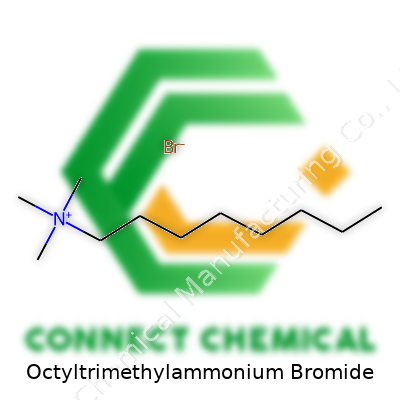

Understanding Octyltrimethylammonium Bromide

In the world of chemistry, a clear formula can tell you a lot about a compound’s real-life character. Octyltrimethylammonium bromide shows up with the formula C11H26BrN. It sounds like a mouthful, but the basics are simple: you’ve got a long hydrocarbon chain (the octyl part), a common ammonium head, and a bromide riding shotgun. That combo turns out to be important for more than one reason.

Why This Formula Catches Attention

Octyltrimethylammonium bromide doesn’t get much love in everyday conversation, yet anyone who’s spent time in a chemistry lab knows it by reputation. As a quaternary ammonium compound, it loves breaking through greasy barriers. I remember scrubbing glassware that seemed untouched by regular soap. Add a solution of this stuff, and stains just slide right off. That cleaning power links back to the formula—one part grabs water, another grabs grease, and together, they chase filth off surfaces. There’s a reason serious labs stock it.

Synthetic chemists use the formula strategically. The octyl chain, with its eight-carbon backbone, is long enough to both dissolve and interact with oily substances. Match that with three methyl groups clinging to the nitrogen, and you’ve got a shape designed for both dispersal and attraction. Bromide’s not there by accident, either. As a counter-ion, it helps maintain molecular balance and lends stability during reactions. It plays a critical role, especially in phase transfer catalysis—helping substances mix that normally refuse to, like oil and water. In my own projects, blending polar and nonpolar reactants without some ammonium salt usually wasted hours and yielded nothing. Throw this compound in, and suddenly, everything flows.

Impact Beyond the Lab Bench

We’re living in a moment where people want their cleaning agents to hit hard without leaving behind toxic waste. Facing regulations and growing consumer awareness, researchers are hunting for options that break down safely. Octyltrimethylammonium bromide walks a narrow path—it works well, but throw it down the drain in large amounts, and water systems feel it. I’ve seen local river cleanups where excessive ammonium compounds fueled algae blooms. Fish populations drop, and suddenly, everyone notices. The lesson sticks: what helps in the lab can hurt outside it. Knowing the formula helps you handle it right, treat waste carefully, and make smarter choices about solvents and cleaners.

Room for Safer Chemistry

Some researchers now explore ways to tweak the formula. Maybe chop off a few carbons or swap bromide for another ion. The idea is to keep the cleaning punch while making disposal safer. Biodegradable surfactants and less persistent molecules are edging into the spotlight. I keep an eye out for green certifications and updated guidelines, knowing every improvement matters. Even a small change to the formula can shift environmental impact, which means paying careful attention isn’t just a chemistry nerd’s obsession—it’s a responsibility.

Solutions for Responsible Use

Anyone working with octyltrimethylammonium bromide gets a chance to lead by example. I label and store it where spill risk drops to almost zero. Colleagues discuss safer handling and push for less waste, keeping water clean for everyone down the line. Knowledge about the formula isn’t just theoretical—it guides real decisions that ripple far beyond the beaker.

What is Octyltrimethylammonium Bromide?

Octyltrimethylammonium bromide (OTAB) turns up in chemical labs and some manufacturing setups. It’s a type of surfactant, helping mix oil and water or making certain reactions run smoother. Sometimes, it gets called a “quaternary ammonium compound” by chemists. The real question is whether this stuff poses a danger—either to those working with it or to folks who might get exposed another way.

Health Hazards: What Happens with Direct Contact?

Getting OTAB on your skin or in your eyes may lead to irritation. Some research shows quaternary ammonium compounds can cause redness or a burning feeling with skin contact, and a splash to the eyes might sting. Long sleeves and gloves are standard not just for this reason, but because nobody wants to tempt fate. Breathing in the powder or vapor could tickle your throat or bother your lungs. While my work with surfactants has never resulted in dramatic mishaps, it only takes one careless move to turn curiosity into a trip to the wash station. Responsible labs label OTAB as hazardous and train their teams to handle spills or skin contact fast.

Swallowing or Inhaling: The Bigger Threats

Ingesting OTAB isn’t something anyone plans on, but accidents do happen. Most sources, including safety data sheets and government chemical databases, agree that these compounds can harm the gastrointestinal tract and might even impact the nervous system in large enough doses. Workers exposed to high levels over time could show symptoms like nausea, dizziness, or headaches. The chemical’s structure means it can cross barriers in the body more easily than some less complex compounds. As for inhalation, the powder form deserves respect—once airborne, its small particles can reach deep into the lungs. Chronic exposure ought to be taken seriously, and it’s best not to gamble with damaged protective equipment.

Environmental Concerns

Using any quaternary ammonium compound brings questions about water systems and aquatic life. OTAB isn’t an exception. These substances can hang around in water for quite a while, and studies suggest impacts on fish and microorganisms. Quats aren’t super biodegradable, which means they can build up. Facilities with proper filtration and disposal methods keep most of the risk in check, but spotty oversight or shortcuts spell trouble for downstream neighbors. I’ve seen wastewater test results turn up unexpected traces of chemicals like OTAB long after the initial disposal, which shows how tough cleanup can get.

Reducing the Dangers: Simple Steps that Work

Keeping risk low for workers requires a few basics — gloves, goggles, masks if dust gets loose, and fresh air in the work area. People should get clear rules on how to store OTAB so it won’t spill or spread, and clean-up kits need to be easy to find. In my experience, regular reminders and “near miss” recounts keep safety real, not just a checklist item. For waste, organizations benefit by following the best practices for hazardous chemical disposal, never sending leftovers down the drain. Manufacturers and suppliers ought to update safety sheets as studies reveal more about OTAB’s possible dangers, helping everyone make informed decisions.

Science, Regulation, and Personal Responsibility

Authorities like OSHA and the European Chemicals Agency list OTAB as hazardous, so the information stands on solid ground. Workers and managers can push for safer alternatives if risks seem high, or just lock in solid prevention routines. Honest discussion and knowledge-sharing help everyone—from the lab bench to local water authorities—keep the invisible risks from becoming tomorrow’s problem. Ultimately, it boils down to respect for what might look like just another white powder sitting on a shelf.

Understanding the Risks of Lax Storage

Octyltrimethylammonium bromide doesn’t look dangerous on first glance. The white crystals seem harmless, but a closer look at the data tells another story. Touching it with bare hands irritates skin, and breathing in its dust can make anyone’s day a lot worse. It even causes real harm to the environment if washing down a drain. Anyone who has spent time in a research lab knows it takes a small mistake for cleanup to become an emergency.

Lessons From Everyday Lab Work

Letting any chemical lie around open invites trouble, and quaternary ammonium compounds like this one demand extra care. Scientists running busy benches learn fast that even a single open jar draws flies—spilled powder turns floors slippery and seems to spread everywhere, ending up on door handles or keyboards. The powder clumps if it gets damp, making it impossible to weigh out correct amounts for the next experiment. Once, a rushed grad student left the lid loose, and the dehumidifier struggled all night pulling the scent out of the air. The lesson stuck: seal things up and don’t cut corners on storage.

Moisture, Light, and Temperature: Enemies of Safety

Manufacturers pack this compound with tight lids because it loves to absorb water. Humidity turns it sticky and causes slow degradation, tweaking how it works in a reaction. Direct sunlight matters more than some expect—it can break down organics or mess with color, making monitoring more difficult. Storing chemicals next to radiators or in windowsills seems convenient until containers warp or crack, risking the whole lot.

Safe Steps—Practical and Proven

Good storage means keeping it in airtight containers, out of sunlight, off the floor, and away from heat. Polyethylene or glass works best. Tucking it onto a powder shelf at room temperature, away from acids and oxidizers, helps avoid mishaps. Labels show date received, and the user’s initials, making it simple to track who last handled it. Expiry dates aren’t a joke—using off-smelling material can ruin projects and risk fines or lost time.

Chemical hygiene officers set clear rules at most universities, backed by federal guidance. The Occupational Safety and Health Administration publishes recommendations, urging sturdy shelving, spill trays, and locking doors if the space sits unattended. Regional environmental agencies ask for logs or inventory sheets. A small expense on proper cabinets saves time and headaches in the long run.

Personal Choices Shape Safety

It’s easy to skip steps late at night or after a long day. Still, one overlooked container can lead to a write-up or weeks lost on troubleshooting. I learned from colleagues who marked their containers in bold marker with hazards spelled out—no one wants to fumble for a datasheet mid-accident. Glove use, keeping goggles handy, and quick access to a spill kit all play a role in safe storage routines.

Simple Steps Leave Lasting Impact

Octyltrimethylammonium bromide poses little risk if treated with respect and attention. Every bottle tucked away, every label double-checked, every glove worn, builds confidence and safeguards the lab, equipment, and the people working in it. Responsible storage lessens risk, protects results, and prevents avoidable disasters, making work both safer and more efficient for everyone involved.

What Makes Octyltrimethylammonium Bromide Unique?

Octyltrimethylammonium bromide, known by chemists as OTAB, caught my attention back in grad school. Surfactants like this form the backbone of many lab techniques, and OTAB often sparks curiosity when talk turns to why some substances mix so well with water—while others just float away. The root of its behavior traces directly to the structure of its molecules. Each OTAB molecule sports a long hydrocarbon tail and a charged ammonium head, with a bromide tag-along.

Mixing with Water: The Dual Personality Effect

Pour a pile of OTAB into water, and a surprising thing happens—the powder dissolves, but only up to a certain point. This molecule wears two faces: the hydrocarbon tail shies away from water, curling up every chance it gets, while the trimethylammonium head interacts freely with water molecules through ionic interactions. The soluble part kickstarts the whole process, latching onto water’s dipoles. The hydrophobic tail works against this, and as the solution gets crowded, the tails start hiding together, forming structures called micelles. Micelle formation serves as a natural limit for OTAB's solubility in water. This trait shapes its use as a phase transfer catalyst, especially where chemists need to bring substances together that usually won’t mix.

Organic Solvents: More Room to Stretch Out

People sometimes ask if OTAB could dissolve better in organic solvents. The short answer: it depends. Polar organic solvents like ethanol let both halves of OTAB feel at home, so OTAB dissolves quite well. Move to less polar solvents (say, chloroform or ether), and OTAB, despite its non-polar tail, bumps into trouble. The ionic head resists, and full dissolution often drops. One study tested OTAB in solvents like methanol, acetone, and benzene—the solubility falls off as solvent polarity drops. The data support what anyone working in the lab would see: the ionic character gives OTAB that boost in polar solvents.

Real-World Uses Shaped by Solubility

Manufacturers developed OTAB for more than just chemistry demonstrations. Thanks to its balanced solubility, it’s a mainstay in making emulsions and nanoparticles. Without these, drug delivery wouldn’t look the way it does now, and experienced pharmaceutical formulators rely on OTAB’s dual preferences to wrap and transport drugs inside the body. Environmental scientists also use surfactants like OTAB for water treatment, marshaling those micelle-forming tendencies to scoop up oily contaminants or heavy metals.

Challenges and Safer Handling

Anyone who spends long hours in a lab knows that unnecessary exposure adds up. OTAB’s broad utility means safety stays central in planning. Splashes in the eye or on the skin prompt quick action—wash and move on. Some studies hint at mild toxicity, especially with long exposure. It underscores the push toward better labeling, improved PPE, and training staff to spot trouble before it grows. Labs and production lines ramp up ventilation and encourage gloves, and digital logbooks help track any exposure over time.

Improving Outcomes by Understanding Solubility

Better awareness of OTAB’s solubility profile leads to fewer mistakes and smoother experiments. I have seen colleagues waste hours chasing a stubborn emulsion with the wrong solvent. Data-driven approaches—consulting the literature, running small tests—save gallons of solvents and dozens of lab hours. Simple steps, like adding salt to encourage micelle formation or tweaking temperature, often unlock the trickiest solubility cases. Chemistry starts on paper, but good sense and careful hands keep mistakes away from the bench.