Tetraethylammonium Hydrogensulfate: An In-Depth Commentary

Historical Development

Scientists started studying the chemistry of quaternary ammonium salts well before the second half of the twentieth century. Out of this field, tetraethylammonium hydrogensulfate (TEAHS) grabbed attention thanks to early curiosities around its unique ionic nature and practical role in physical chemistry. Synthetic organic labs in the mid-1900s explored how such salts shaped ion transport in solution; only years later did electrochemical research start relying on TEAHS as a dependable supporting electrolyte. Its reputation among chemists possibly set in earnest across the 1960s and ’70s, as broader interest in organic salts and their interactions in aqueous or nonaqueous media took off. Having handled TEAHS in university, I recall the dependable white crystalline powder in reagent bottles—you don’t forget the slightly tangy but sharp scent, the firm texture, and the strict warnings companies included due to its corrosive nature. Even today, TEAHS stands as both a legacy and a workhorse among ionic compounds in the laboratory.

Product Overview

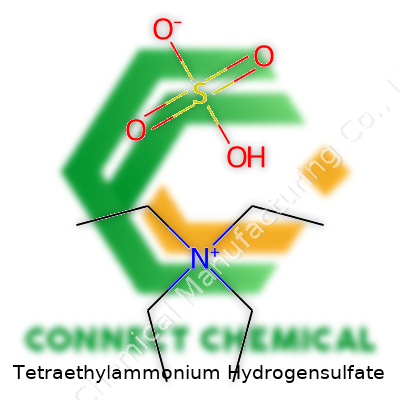

Tetraethylammonium hydrogensulfate appears as a solid salt, commonly sold in white crystalline form. Most suppliers tailor their labeling to match chemical purity standards—over 98% is standard for lab grade. The structure involves a tetraethylammonium cation paired to a single hydrogensulfate anion (C8H21NO4S), making it easier to spot cross-disciplinary interest, from synthetic chemistry to bioelectrical research. You won’t find any frills here: it’s a salt through and through, stable on the shelf if kept dry, and straightforward to handle if you respect its acidic and corrosive tendencies.

Physical & Chemical Properties

TEAHS offers a melting point near 178–181°C—a property I’d always remember, watching it hold up well under gentle heating plates. High water solubility stands out in lab records and from experience: a solid chunk seems to just vanish as you swirl it in deionized water, with the resulting solution picking up on the hydrogensulfate’s moderate acidity. Beyond water, it promises strong solubility in polar solvents like ethanol or methanol. Chemically, the salt resists decomposition under standard storage and doesn’t lose structural identity unless severely heated. A big attractor for electrochemists stems from its broad electrochemical window and minimal tendency to coordinate with metal cations; it stays out of the way during redox measurements, which is no small feat compared to some other ammonium salts.

Technical Specifications & Labeling

Reagent bottles, at least in the institutions I’ve worked, indicate purity, hydration state, and batch number. For certified quality, labs stick to minimum standards: 98-99% purity, non-hygroscopic form, and absence of any obvious discoloration or excessive particulate matter. Durable polyethylene or amber glass containers with secure, tamper-evident lids keep out moisture. Labeling includes hazard statements about skin and respiratory irritation as well as mandatory handling symbols—no shortcuts allowed per OSHA or GHS guidelines. Since spectroscopic and chromatographic applications rely on interference-free background, chemical specification sheets detail residual water content, sodium, potassium, and common metal ion traces, all of which can mess up precise readings.

Preparation Method

Synthesizing TEAHS isn’t especially complicated in a capable lab but requires patience and the usual acid-base respect. The standard approach brings tetraethylammonium hydroxide into careful titration with concentrated sulfuric acid. Mix them slowly, usually in an ice bath to control exothermic heat. Stirring helps prevent localized overheating—watch the pH; as soon as a faint acidic point registers, you’re nearly there. Evaporate the solution under reduced pressure, then let crystals form as the solvent dwindles. Wash the product with nonpolar solvents; recrystallization often follows to flush out leftover impurities. The process drives home lessons about acid-handling—from proper glassware to gloves and goggles—and attention to detail, since a small slip can spoil purity or even ruin a batch.

Chemical Reactions & Modifications

Most reactivity centers on the hydrogensulfate anion—bring in strong bases, and you’ll wind up with the neutral sulfate salt and water. Throw it into mixed-solvent systems with organic bases or acids, and you’ll spot exchange reactions churning out other quaternary ammonium salts or harnessing the hydrogensulfate as a counter-ion in synthetic transformations. TEAHS can participate in phase-transfer catalysis, though it plays second fiddle to more lipophilic analogues. A handful of organics labs use it as a starting point to derive larger tetraalkyl analogs, especially for custom synthesis routes where cation identity shapes solubility or crystallinity. I’ve seen students try to push its reactivity, but most end up marveling at its stubborn solid-state nature outside those canonical ion-exchange or proton-transfer scenarios.

Synonyms & Product Names

Much of the literature calls it Tetraethylammonium bisulfate, a nod to the hydrogensulfate formula. You’ll see shorthand as TEAHS, TEA hydrogensulfate, or even TEA·HSO4 among veteran chemists. Reagent catalogues opt for the full chemical descriptor to avoid confusion: N,N,N,N-Tetraethylammonium hydrogensulfate. Some older references relate to ammonium ethyl sulfate, but that name rarely appears outside archival journals.

Safety & Operational Standards

Working with TEAHS means recognizing the risk factors that come with both corrosive anions and quaternary ammonium cations. Short exposure leaves mild skin and airway irritation; longer, repeated contact risks dermatitis or more stubborn respiratory effects. Regulatory guidance from OSHA, GHS, and EU directives requires safety goggles, gloves, and ideally a fume hood—certainly not optional in modern labs. TEAHS also breaks down in heat to release toxic gases, so careful thermal practices forbid open flames or strong oxidizers nearby. Spill protocols stress quick absorption with inert media and strict segregation from incompatible substances like alkalis or oxidizers. Disposal follows hazardous material codes—straight into the general chemical waste stream with acidic annotation. Not everyone likes the paperwork, but tracing every step prevents nasty surprises, especially in institutional settings with large student or staff populations.

Application Area

TEAHS claims its spot in electrochemical research as a top supporting electrolyte for polarographic and voltammetric studies. It doesn’t latch onto active metals, keeping results clean in both aqueous and nonaqueous investigations. Biologists who chase nerve impulse mechanisms rely on it to block potassium channels without the confounding effects that come from sodium or lithium interference. The salt helps dissolve problematic organics in analytical labs, sometimes doubling as a phase transfer agent or solubilizing additive in synthetic or preparative chemistry. Outside pure science, a handful of pilot-scale processes in pharmaceutical and fine chemical manufacturing employ it to steer specific ion-pairing mechanisms or extract valuable actives, though its use doesn’t stretch as far industrially as broad-spectrum ammonium salts like tetrabutylammonium bromide. Still, its performance in low-concentration, high-purity conditions leaves plenty of room for scientific applications.

Research & Development

Recent years have seen renewed interest in TEAHS in the context of advanced batteries and electrolytic systems, especially as scientists watch ionic liquids and room-temperature salts for next-gen energy storage. Structural modifications of ammonium salts feed into a wider hunt for robust, thermally resistant ionic conductors—TEAHS’s stability and high conductivity in water position it well in basic feasibility studies. Its role in neurological studies endures, as experimental pharmacologists use it to probe potassium ion channel dynamics. Some research groups tinker with functional analogs, hoping to replace the hydrogensulfate anion for more specialized solvating or conducting properties; the ease of making TEAHS and the predictability of its chemical behavior keep it in the lead. Slow but steady work also checks its reactivity as a counter-ion in green chemistry—an area where minimal waste and inert byproducts always matter.

Toxicity Research

Lab accident records, animal studies, and cellular assays all tell similar stories—prolonged exposure or high doses irritate tissues, with acute oral toxicity studies in rodents reporting low LD50 values in the several hundred milligrams per kilogram range. Chronic inhalation data is sparse, but occasional reports link repeated, accidental contact to skin sensitization and, at worst, strong corrosive damage upon direct dosing. Regulatory agencies flag it for its corrosivity, not as a systemic toxin, yet most institutional MSDSs list it as hazardous due to lack of long-term epidemiological data. Recent cell culture work checks its capacity for membrane disruption or residual impact on mitochondrial integrity, and findings suggest that risks don’t become overwhelming unless substance mishandling or accidents come into play. Teachers and supervisors emphasize clear labeling and repeated training for a reason—nasty outcomes rarely stem from the compound itself, but more often from taking shortcuts with safety gear.

Future Prospects

TEAHS likely won’t fade from academic or applied chemistry any time soon. The ongoing hunt for better ionic conductors, more predictable supporting electrolytes, and effective, water-soluble phase catalysts keeps demand steady. Advances in battery electrolytes, electrochemical sensors, and phase transfer technology push researchers to revisit classic compounds like TEAHS for inspiration and ready-to-use models. As stricter guidelines for chemical safety, waste reduction, and traceability shape research cultures, compounds with straightforward handling routines and consistent performance remain desirable. With ongoing work in synthetic methods, green chemistry, and neurological research, TEAHS continues to link century-old science with current innovation.

Chemistry In The Real World

Tetraethylammonium hydrogensulfate isn’t a name you’ll spot at the corner store, but it shows up in a lot of labs and advanced manufacturing. Chemists use this salt because it helps coax molecules to behave in specific ways when running reactions. Its main appeal comes from its strong ionic nature and its neat, chunky tetraethylammonium cation, which doesn’t get in the way much but keeps things balanced.

Why Scientists Like It: Electrochemistry And Synthesis

In my time mixing solutions in university labs, having the right supporting electrolyte often meant the difference between getting clean, readable electrochemical data or just a frustrating mess. Tetraethylammonium hydrogensulfate stands out in research focusing on electrochemistry. Electrodes count on the steady stream of ions in solution, and this compound supplies them. It dissolves well in many solvents, allowing current to travel smoothly. Researchers working on battery prototypes or new types of fuel cells turn to it for that reason.

Besides powering up test tubes, this salt steps up during organic synthesis. Some chemical transformations need a source of the hydrogensulfate ion, but adding basic ammonia or caustic acids can sidetrack a reaction or demolish the products. Tetraethylammonium hydrogensulfate lets chemists slip that ion into a mix without shaking things up too much. That can mean higher yields or faster routes to complex molecules, which matters in fields like pharmaceuticals, where every step gets scrutinized for waste and reliability.

Making Measurements Matter

Electroanalytical chemists live and die by the quality of their data. Poorly chosen salts ruin voltammetry experiments, making results noisy or misleading. Tetraethylammonium hydrogensulfate offers stability and clarity. By picking a salt with this size and structure, interference drops. This tightens up currents, locks in potentials, and keeps pH from swinging much. That’s especially important for grad students or industry crews running experiments they’ll present to funding agencies or regulatory bodies. Trust in data keeps careers moving and pushes innovation forward.

Safety And Environmental Responsibility

Using specialty salts brings up safety and environmental questions. Many ionic compounds have nasty side effects if mishandled. Tetraethylammonium salts do not belong in drinking water. Labs stick with proper disposal methods and personal protective equipment. The field is moving toward greener alternatives and better waste treatments, so the hope is people can keep making important discoveries without as much risk to themselves or the world outside. Some companies have started exploring ways to recycle or neutralize lab salts instead of just flushing them out.

Looking Ahead: Room For Improvement

University budgets don’t always stretch far, and specialty salts can drain funds fast. Maybe future researchers will find new mixtures or electrolytes that work as well but cost less or break down more easily. For now, tetraethylammonium hydrogensulfate keeps a firm spot on the shelf, thanks to its reliability and trusted performance in demanding experiments. Folks leaning into green chemistry aim to temper the environmental impact without giving up the advantage offered by salts like this, and that means collaboration between chemists, engineers, and regulators remains crucial.

Breaking Down the Name: Tetraethylammonium Hydrogensulfate

Tetraethylammonium hydrogensulfate isn’t the type of compound you stumble across in most kitchens or garages, but it pops up once you start working around research labs. Naming gives away its makeup—a tetraethylammonium ion paired up with a hydrogen sulfate (sometimes called bisulfate) anion. Tossing together basic chemistry knowledge, the chemical formula comes out as (C2H5)4NHSO4 or sometimes laid out as [(C2H5)4N]+ [HSO4]-.

Real-World Uses: Not Just Lab Glassware

I first saw this compound not in a textbook but in a dusty bottle on a shelf at a campus electrochemistry lab. Tetraethylammonium salts, including hydrogensulfate, show up in nerve research, as they can block certain potassium channels. This isn’t just academic trivia—it helped scientists unlock how nerves send electrical signals, laying groundwork for actual medicine. Understanding these compounds with their proper formulas matters. It cuts down on confusion and mix-ups, especially when similar-sounding compounds do very different jobs.

Industry leans on these types of salts too. In organic chemistry, some reactions demand non-coordinating ions, and tetraethylammonium often steps in. Companies producing pharmaceuticals or cutting-edge batteries depend on precise chemical recipes. Having the wrong formula in the wrong place bottles up production or sends research down the wrong path. Formalizing the chemical formula avoids those headaches and streamlines communication across borders and between specialties.

Formula Accuracy: Trust, Safety, and Transparency

I remember talking with a professor about supply chain headaches—an incorrectly labeled bottle landed in the lab, turning months of work on its head after realizing the mix-up. Clear, correct chemical formulas don’t just keep projects on schedule—they protect safety, too. The ammonium cation shapes everything from handling instructions to how a chemical interacts with others. Hydrogensulfate, being moderately acidic, adds more layers to storage and use. Mistaking it for tetraethylammonium sulfate would throw pH balances off in a heartbeat or even risk an unexpected chemical reaction. Lab safety officers and regulatory watchdogs want clarity, and it all starts with a proper formula.

Where Experts and Learners Meet

Solid science depends on cumulative, shared knowledge. Having the right formula helps students double-check homework, keeps professional chemists from costly errors, and supports industry partners as they scale up units. Reliable sources like standard peer-reviewed databases list tetraethylammonium hydrogensulfate clearly. For curious minds or people starting out, taking the time to match the name and structure with the proper formula is more than rote memorization. It models the detail-oriented mindset that science and safe industry both rely on.

Moving Toward Better Practices

As labs digitize their records and industry supply chains tighten, accuracy in chemical labeling and documentation becomes more important. Standardizing names and formulas, investing in staff training, and ensuring clear communication—these steps strengthen trust at every level, from classroom to factory floor to regulatory agency. That’s how companies and institutions avoid mishaps and keep science moving forward. In the end, a formula like (C2H5)4NHSO4 isn’t just a set of symbols—it’s a passport for research, trade, and safety.

Looking at Safety First

Tetraethylammonium hydrogensulfate isn’t a substance anyone wants lying around the garage or stacked in the corner of a classroom. This chemical, often found in research labs and a few select industrial applications, brings with it a level of respect that comes only from careful handling. In my years working with all sorts of specialty chemicals, I’ve seen what happens when corners get cut with storage, and it’s never worth the hassle or risk. Evidence from the Chemical Safety Board shows that improper storage remains one of the leading causes of lab accidents. A simple label or a sturdy cabinet can mean the difference between a routine day and a trip to the ER.

Understanding What Makes It Tricky

Tetraethylammonium hydrogensulfate reacts sharply to moisture and doesn’t mix well with many common acids or bases. Given its strong ionic nature, exposure to water or humidity causes clumping or, in the worst scenarios, unwanted reactions. Once, a colleague left a jar loosely closed on a shelf next to a humidifier — that one simple oversight ruined the sample and caused a small, avoidable spill.

Beyond just keeping it dry, this chemical holds its own hazards if stored near incompatible materials. Mixing up laboratory shelves runs the risk of creating unsafe conditions. The fact is, even skilled technicians get tripped up if storage guidelines go ignored in favor of convenience.

Smart Storage Makes All the Difference

At the core, a dry, cool storage area with even temperatures works best. Store it in tightly sealed containers, preferably using glass or high-grade plastic that won’t react. Labels should show exactly what the contents are along with preparation and opening dates. Fresh, clear labeling prevents confusion and helps in case someone needs to review intake records — something regulatory inspectors never ignore.

Personal experience in the lab taught me that dedicating a specific section of a storage cabinet for hygroscopic and reactive compounds isn’t just overkill — it’s smart management. OSHA sets strict guidelines for chemical storage, but good habits go beyond just ticking boxes. Locked cabinets with no exposure to direct sunlight keep the compound stable and away from prying hands. In some labs, the good old double containment method — one container inside another — stands as a simple, low-cost buffer against leaks.

Preparation Beats Regret

Stories passed along by veterans in the chemical industry point to one repeating lesson: clear organization beats chaos every single time. An inventory list at the storage area builds an extra layer of accountability. I’ve always relied on regular checks to spot leaks, cracks in lids, or product degradation. Even the best container won’t last forever, so replacing them before there’s an issue pays off.

Addressing waste disposal follows closely behind storage. Used, outdated, or spilled tetraethylammonium hydrogensulfate needs responsible handling — relying on local hazardous waste programs, not tossing it down a drain or in regular trash. The EPA maintains strict oversight here for good reason.

Simple Steps, Real Impact

Proper storage for tetraethylammonium hydrogensulfate isn’t about fussy details; it’s grounded in responsibility and daily habits. Anyone using or keeping this compound owes it to themselves and others to stay organized, communicate clearly, and respect the risks. Small, thoughtful adjustments now save a lot of unwelcome drama down the line.

Understanding the Substance

Tetraethylammonium hydrogensulfate shows up in research labs and certain chemical processes. Folks use it for making organic compounds, running battery tests, and investigating how nerves work in biological studies. This salt, with a long name, seems harmless at first glance—no funny color, no strong smell, and it blends into water pretty easily. Still, just because it doesn’t jump out as dangerous, that doesn’t mean you can toss it around without worry. Every chemical demands respect, especially ones that bring a long list of potential risks if handled carelessly.

Toxicity: Should You Worry?

Stories about this compound don’t make headlines, but its hazards deserve attention. Tetraethylammonium-based chemicals affect living cells because they block potassium channels. Researchers use this effect to dig into how nerves fire or how cells send signals. In lab animals, too much of this chemical causes tremors, muscle weakness, and sometimes seizures. These effects point to clear dangers. Breathing dust or getting the powder on your skin can let some of the compound slip into your system. Swallowing it directly, by accident or careless lab habits, hits much harder—especially for people with underlying nerve or heart conditions.

Handling Risks in Real Life

No one working with chemicals trusts them blindly. Good habits keep problems away. This salt calls for gloves, goggles, and a well-ventilated space. Spills need fast, careful cleanups. You don’t want the powder on your clothes, skin, or eyes. Washing well after work and storing materials tightly sealed cut down on daily risks. I’ve seen folks tuck containers on the edge of a shelf and end up with a nasty spill—simple mistakes cause big headaches if the cleanup involves something that tampers with the body’s electrical signals.

Facts Backing Up Precautions

Sifting through safety sheets, you’ll see warnings about eye and skin irritation. The danger jumps for folks who ignore basic lab rules. Inhaling dust causes coughing, throat burning, and sometimes more severe respiratory trouble. Long-term studies still run short, but the acute risks show up fast enough to take them seriously. Mixing it with strong acids or bases, or heating it carelessly, can whip up harmful fumes. Water runoff from lab sinks drags small amounts into the wider environment, where its impact remains uncertain. Most research looks at what the chemical does inside tightly controlled test tubes, not out loose in streams or soil. Still, it makes sense to keep any potentially harmful lab product from seeping into water or air.

Better Ways Forward

For any workplace using this chemical, better training always pays off. From my own days as a lab assistant, careful instruction meant fewer accidents and faster response when they did crop up. A safety culture comes from folks looking out for each other, not just from checking boxes on a form. Regular equipment checks, honest reporting of near-misses, and a willingness to ask questions make a real difference. Some labs test less hazardous salts for the same research tasks. Substitute chemicals with a lower health risk, even if the process takes a bit more time upfront. This approach swaps out quick wins for long-term safety, a trade I’ll take any day. Lab work always promises discovery. With good habits and the right information, curiosity need not come with hidden dangers.

Why Solubility Matters for Tetraethylammonium Hydrogensulfate

Tetraethylammonium hydrogensulfate doesn't get much attention outside of chemistry circles, but its ability to dissolve in water matters more than most people realize. This compound usually shows up in electrochemistry labs, nerve signaling experiments, and battery research. As someone who's spent countless hours surrounded by lab glassware and strange-smelling chemicals, I’ve noticed researchers turning to tetraethylammonium salts for their reliability as strong electrolytes.

Solubility isn’t just another number snapped out of a handbook—it shapes how scientists use this compound. For Tetraethylammonium hydrogensulfate, easy dissolving in water means experiments run smoothly and solutions stay clear, not clumpy or gritty. The more a material blends into water, the easier life gets for everyone in the lab.

The Real Numbers: Solubility Data

Tetraethylammonium hydrogensulfate is highly soluble in water. That’s the short answer most chemists give, but numbers back it up too. According to Sigma-Aldrich and similar chemical suppliers, over 1,000 grams of this salt will dissolve per liter of water at room temperature. Most labs never push those limits, but seeing the compound vanish into a flask of water without stubborn leftovers shows just how soluble it is.

Not every salt acts this way. Some need hot water or swirling for ages. With tetraethylammonium hydrogensulfate, a gentle swirl usually does the job. It’s as if the positive and negative ions don’t mind pulling apart. The tetraethylammonium cation is bulky, but water molecules squeeze around it with ease, helped by the hydrogensulfate anion’s own attraction for water. If you want an analogy: sugar cubes dissolve only if water can work around the crystal edges, while table salt melts away much faster; tetraethylammonium hydrogensulfate acts more like the salt than the sugar.

Uses and What Solubility Brings to the Table

The reason folks care about solubility here ties back to research in nerve blockers, batteries, and even analytical chemistry setups. A compound dissolving quickly and fully means the ions get busy right away. In battery research, people look at how well ionic liquids can conduct electricity. Stubborn, half-dissolved powders only clog progress.

One challenge comes from preparing concentrated solutions. At very high concentrations, not every compound keeps mixing like it does at lower ones. The good news is, most published recipes don’t run into problems unless someone tries to make thick slurries. For typical research use—anywhere from millimolar up to molar concentrations—the salt stays friendly in water.

Troubleshooting and Safe Handling

With something this soluble, spills turn into clean-ups instead of sweep-ups. I’ve seen new students pour too quickly and watch nervous foam bubble up. Keeping the pace slow, pouring the powder in bit by bit, avoids surprises and waste. And while tetraethylammonium hydrogensulfate doesn’t rank among the most dangerous chemicals, it deserves routine gloves-and-goggles respect. Always check the latest Safety Data Sheet, and never treat clear liquids like water just because they’re water-clear.

Room for Smarter Practices

Over the years, I’ve learned that storing solutions in tightly closed bottles beats trying to dissolve the stuff every single time. Accurate labels, along with clear note-taking, save hours. Given how soluble Tetraethylammonium hydrogensulfate is, it invites creative applications. As labs consider greener solvents and smarter electrolytes, this compound’s ready-to-dissolve nature puts it near the front for future experiments.