Tetramethylammonium Chloride: Tracing the Journey from Discovery to Modern Utility

Historical Development

Chemicals often trace their origins to a single curiosity in the lab. Tetramethylammonium chloride sprang out of the late-19th-century boom in quaternary ammonium compounds. Chemists experimented with methylating ammonia, intrigued by the way structure influenced behavior. Early research in England and Germany highlighted its water solubility and tendency to form stable salts. As organic chemistry developed, this simple salt found roles far beyond what its inventors could have guessed. It moved quickly from an oddity in glass vials to a research chemical, then into industry, each time opening up new questions. Early efforts did not focus much on safety or environmental concerns, but over the next several decades, growing awareness demanded more attention to handling, exposure risks, and environmental impact. By the 1960s, academic and industrial labs both saw it as an essential reagent, and regulatory standards began to keep pace.

Product Overview

On the shelf, tetramethylammonium chloride looks modest. It sells as a fine white crystalline powder, labeled clearly with its name, chemical formula (C4H12NCl), and purity. The compound appeals for its reasonable cost, good shelf stability, and the way it slips into so many laboratory processes. Most commercial material arrives with purities above 98%, with moisture content carefully controlled to protect integrity during transport. Companies choose packaging to reduce static buildup and accidental exposure; wide-mouth plastic or glass jars prevail in research contexts, while larger drums—lined for chemical resistance—pop up in factories handling scale-up synthesis. Chemists recognize it for reliability and ease of use, a tool to push complex syntheses forward or provide a strong base for further modifications.

Physical & Chemical Properties

Tetramethylammonium chloride won’t win a beauty contest, but its clean white crystals tell a story. It melts at about 241°C, staying stable before decomposing. The salt dissolves easily in water and alcohol, sending out a faint amine scent under the nose. Unlike many organics, it does not burn, instead releasing methylamines and hydrogen chloride if forced into decomposition in the absence of air. The compound holds up well in closed storage, resisting clumping and caking unless exposed to floor-level humidity or leaky stoppers. Its ionic nature underscores a strong affinity for water and gives solutions a slightly alkaline taste—though, obviously, ingesting lab-grade substances always poses risks. Many chemists appreciate the foolproof nature of its solubility and the lack of unpleasant surprises during handling.

Technical Specifications & Labeling

Producers publish details on batch labels and datasheets, including molecular weight (109.6 g/mol), CAS number (75-57-0), and purity, often breaking down trace impurities such as residual methylamine or chloride content. Customers care about water content, as high levels can change the salt’s performance in reactions like methylations or phase-transfer catalysis. Labels print hazard signals with pictograms where regulations require—indicating both toxicity on ingestion and irritation on contact. Barcodes enable quick tracking for labs managing dozens of chemicals, and most suppliers now list recommended storage temperature (room temperature, dry conditions) right on the front. Transparency here supports safe use and prevents costly mix-ups, particularly in busy academic settings.

Preparation Method

Tetramethylammonium chloride comes from the alkylation of ammonia. Manufacturers bubble methyl chloride through a cooled solution of concentrated aqueous ammonia. As the mixture reacts, tetramethylammonium chloride forms and drops out. After filtering and washing away residual byproducts, companies recrystallize the salt to purify it, often turning to activated carbon and careful solvent selection to remove color and trace organics. As experience shows, small operational tweaks—slower feed rates, better coolant flow, tighter pH checks—keep product quality high. Waste gases and effluents prompt attention; environmental controls now capture and neutralize methylamine emissions, part of a broader trend toward cleaner manufacturing in chemistry.

Chemical Reactions & Modifications

In the lab, tetramethylammonium chloride usually finds itself serving as a methylating or phase-transfer reagent. The cation can swap its chloride for other counterions such as hydroxide, sulfate, or carbonate, each with its uses. Chemists replace chloride with hydroxide to generate tetramethylammonium hydroxide, a strong organic base that etches silicon wafers and helps in analytical chemistry. Another avenue runs through the conversion to other halide salts, useful in organic synthesis or as ionic liquids in catalysis. This flexibility springs from its structure—four methyl groups around a nitrogen, each easily manipulated, yet stable enough to avoid random breakdown. It doesn’t take much to see why researchers appreciate its role as a building block, neither too aggressive nor too inert, fitting a "middle ground" where control matters.

Synonyms & Product Names

You’ll spot tetramethylammonium chloride under different names in catalogs. "Quaternary ammonium chloride" appears in older manuals. Some suppliers abbreviate to TMAC or TMA-Cl, especially in product lists. International trade references lean on the IUPAC name, and non-English regions sometimes translate the "tetramethyl" portion, but most stick to recognizable variants to avoid confusion. Researchers swapping tips online or trading protocols usually settle for "TMAC," saving time and avoiding mix-ups with other quaternized amines. Knowing these synonyms streamlines cross-referencing between suppliers and technical guides.

Safety & Operational Standards

Safe handling of tetramethylammonium chloride has changed a lot since the compound hit labs. Research pointed to potential toxicity and possible nervous system effects with enough exposure. Gloves and eye protection sit on benches whenever the jar opens. Hood work prevents inhalation of fine dust, since the powder can cause respiratory irritation and headaches in sensitive workers. MSDS sheets spell out steps for spills—scoop, ventilate, wipe down, bag up. Most labs keep neutralizing agents and first aid instructions posted. Storage calls for tight seals away from acids or bases to avoid unwanted reactions. Regular safety audits ensure compliance, while folk wisdom from seasoned chemists encourages double-checking even familiar materials. Waste disposal follows regulated procedures, with dedicated containers marked for quaternary ammonium salts and transportation coordinated through certified contractors.

Application Area

Research chemistry, electronics, pharmaceutics, and analytical labs all draw on tetramethylammonium chloride for its practical value. Engineers trust it to promote etching on silicon wafers, a job where precision and purity decide the entire process. Analytical chemists exploit its capacity to adjust ionic strength in solution, stabilizing unusually reactive systems. Synthetic chemists slot it into phase-transfer catalysis and as a methylating agent in complex reactions. Pharmaceutical researchers scrutinize its structure-activity relationship, trying to tweak the base for new drug candidates or better delivery systems. Environmental labs sometimes use it to test water samples or study the fate of quaternary ammonium salts as potential pollutants. Each domain demands reliability and safety, pressing for ongoing improvements in sourcing and formulation.

Research & Development

Ongoing work spotlights tetramethylammonium chloride’s role in greener synthesis and cleaner processing. Academic labs push to understand the way its hydrophilic head and size influence behavior in ionic liquids—opening doors to solvent-free chemistry and unconventional catalysis. Nanotechnology researchers seek cationic surfactants that build stable, controlled nanostructures for sensors or medical devices, with TMAC serving as a launch pad. Teams map out reaction pathways, using computational models to predict how changing anion partners might tune properties for specific roles. Biotechnology applications look at its performance in protein purification and as a buffer in certain high-precision enzyme assays. This hunger for knowledge fuels patents, refined production, and the search for alternatives that match or surpass its safety record.

Toxicity Research

Tetramethylammonium salts raised eyebrows when animal studies and case reports noticed toxic effects at moderate doses. Researchers report that oral or injected exposure led to tremors, muscle weakness, and, in some cases, death in lab animals. The chloride acts directly on the nervous system, blocking acetylcholine receptors in a way reminiscent of certain neurotoxins. Most cases of harm trace back to accidental exposures or mistakes with poor labeling. Long-term risks in people stay low under careful lab practice, though authorities recommend limiting airborne dust and wearing protective gear during handling. Ingesting, inhaling, or spilling the concentrated material can bring on chemical burns or systemic toxicity. Because of these hazards, some countries impose tight controls on sales and distribution, especially for bulk quantities. Ongoing research continues to probe chronic low-level exposure, especially as these salts turn up in wastewater and new technology products.

Future Prospects

The path forward for tetramethylammonium chloride ties into major changes in synthetic chemistry and environmental control. Efforts to cut chemical waste and energy use drive interest in alternative manufacturing routes and greener byproducts. Innovation in ionic liquids promises to boost its use in battery electrochemistry, high-efficiency separations, and even scalable carbon capture technologies. Regulation will probably get tighter, especially concerning disposal, personal exposure, and emissions during production. As green chemistry evolves, companies and researchers look at whether modifications or bio-based alternatives can meet demand with lower health or ecological risks. Still, the need for reliable, stable, straightforward reagents keeps it on the procurement lists, a nod to the old rule that practical tools often outlast high-profile trends in chemistry.

Lab Benches and Industrial Floors

Working in a research lab, I remember sharing stories about the countless white powder bottles lining our shelves. Tetramethylammonium chloride, or TMAC, showed up in almost every physical chemistry set I encountered. This simple salt, built from four methyl groups connected to a nitrogen atom, packs much more punch than its humble label lets on. Chemists often reach for it to tweak reaction conditions, especially when sharp control over solubility or ionic strength is needed. TMAC’s affinity for water gets noticed—unlike some chunky salts, it dissolves fast and clear, which matters for anyone mixing solutions where consistency counts.

A Tool in Organic Synthesis

Organic chemists lean on TMAC for quaternization reactions. This specific salt participates in creating quaternary ammonium compounds, which then go into pharmaceuticals, dyes, and surfactants. I’ve seen TMAC help mediate the exchange of ions in critical steps toward molecules used in cancer treatments and heart medications. Colleges teach about its role in phase-transfer catalysis, turning tough two-phase reactions into straightforward, single-pot processes. This practical use spreads from academic labs to specialty chemical plants, reinforcing its reputation as more than a simple lab reagent.

Electronics and the Modern World

Device fabrication brings TMAC into new focus. Many don’t realize that this compound helps shape the way microchips and circuit boards come together. In the semiconductor world, TMAC sometimes acts as an etching agent, helping to trim away unwanted material with precision. Its predictability and the clarity it brings to reaction baths ensure manufacturers keep production lines humming without unwanted hiccups. As consumer electronics keep shrinking, the need for high-purity chemicals like TMAC grows. Any shortfall in purity can trigger failures, so producers always track their suppliers and quality control tightly.

Water Treatment and Environmental Footprints

Treatment plants add TMAC derivatives into the mix to adjust water’s properties. This helps tune the flow of ions, letting plant managers optimize how they remove contaminants. I’ve talked to engineers who depend on reliable, predictable behavior from their inputs. If TMAC batches ever arrive contaminated, plant performance could drop, messing with everything from taste to toxin removal.

Risks and Responsible Use

Handling TMAC deserves respect. This salt can irritate skin, eyes, and airways, which reminds me of those long days in the hood with gloves and goggles firmly in place. It’s not just a workplace issue, either—spills or poor disposal threaten aquatic systems, since quaternary ammonium compounds stick around and upset algae and fish populations. Communities living around factories or disposal sites sometimes raise concerns about possible leaks and long-term health risks. These worries push for tighter regulation and smarter waste management.

Looking Ahead

Efforts to recycle chemicals like TMAC stand out as one clear path forward. Companies invest in closed-loop systems, capturing and reusing valuable compounds rather than flushing them away. Labs and factories now track every gram, aiming for records that prove responsible handling from shipment to disposal. The future probably includes more use of alternatives with shorter environmental footprints where possible, but for now, TMAC’s versatility keeps it in play across many industries—and safety always sits at the center of responsible practice.

Understanding Tetramethylammonium Chloride

Tetramethylammonium chloride falls into the category of quaternary ammonium compounds. It shows up in chemical catalogs as a reagent for research or industrial work, often helping in organic synthesis or as a phase-transfer catalyst. Its widespread use doesn’t mean it’s benign. Hazards often get downplayed until someone mishandles the material or forgets protective gear in a rush to meet a deadline.

Recognizing Toxic Effects

Peer-reviewed studies highlight real risks. Accidental exposure to tetramethylammonium compounds brings trouble fast. The substance penetrates through skin, lungs, or mouth, then jumps into action in the body’s nervous system. Published case reports document toxic symptoms such as muscle twitching, sweating, headaches, confusion, rapid heartbeat, low blood pressure, and seizures. Fatalities have been linked to high doses, as detailed in the American Journal of Emergency Medicine. That kind of data should pull the alarm for those tempted to brush off the hazard warnings printed on each bottle.

Shortcuts and Real Life Incidents

Shortcuts don’t pay off. Chemical safety isn’t just for the big emergencies or imaginary worst cases. In my own university lab days, strict glove and goggle rules got old quickly, but hearing about an accidental splash in a neighboring department, and the aftermath in the medical center, convinced everyone to enforce them. Eyes and skin carry the fastest routes for this salt to wreak havoc. Heating it, or releasing dust, isn’t smart either, since inhaled traces set off respiratory problems or worse.

Environmental Concerns

The environmental footprint shouldn’t get overlooked. Tetramethylammonium salts dissolve right into water supplies, and wastewater from labs can ferry contaminants much farther than the campus perimeter. Studies have found it hard for water treatment systems to fully break down quaternary ammonium compounds, raising questions about long-term effects on fish and microorganisms. Waste disposal practices must shift from “convenient” to “responsible,” or else these risks come home in the drinking water.

Fact-Based Precaution

A little research brings up the recommended exposure limits. The National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) points to the dangers of tetramethylammonium salts as neurotoxins. Regulatory bodies say to handle these chemicals inside chemical fume hoods, to keep containers shut tight, to don chemical-resistant gloves, and to wear eye and face protection every single time. These aren’t overly cautious rules, just common sense and science speaking loud and clear.

Improving Safety Culture

It takes reminders and regular talks about real incidents to keep everyone vigilant. Training can’t be a box-ticking task. Safety data sheets help, but drills for spills or accidental contacts push home why protocols matter. Managers, teachers, and lab leaders carry responsibility to model good habits and call out risky shortcuts, even on the busiest days.

What Should Happen Next?

Proper storage, clear labeling, and regular re-training build a protective barrier between people and dangerous chemicals. Substitution by safer reagents, where possible, deserves more attention from chemists designing experiments. Manufacturers should stay transparent, updating users about emerging toxicity data for the wider family of quaternary ammonium compounds. In the bigger picture, these conversations keep everyone mindful of health, safety, and environmental integrity in scientific and industrial work.

Everyday Lab Experience Highlights Risks

Anyone who has spent time in a lab knows the drill. Some chemicals don’t ask for much—they hide away in a drawer or under a bench. Tetramethylammonium chloride asks for more. I’ve seen coworkers take shortcuts, storing bottles next to sinks or near direct sunlight, and then getting frustrated when the compound changed character or even leaked. This compound calls for proper storage, and ignoring the basics risks more than just wasted money.

Real Hazards, Real Lessons

Tetramethylammonium chloride isn’t something to treat lightly. It can release toxic fumes if burned and reacts with strong oxidizers. Forgetting a container open or letting humidity seep in creates both safety and quality issues. I’ve handled corroded caps and caked product before—those visual cues keep the importance of safe storage front and center.

Temperature and Humidity: The Enemies of Stability

Lab tests and real-world experience show this salt holds up best at room temperature. Small temperature swings usually don’t matter, but keeping it above 30°C isn’t smart. Humidity changes everything, drawing moisture into the bottle over days or weeks. That shift can ruin an entire batch and throw off experimental results. Plastic containers sometimes don’t seal well enough—glass with tight caps keeps out both water and air much better.

Sunlight and Chemical Neighbors

I once made the mistake of leaving Tetramethylammonium chloride near a window. Sunlight did not destroy the powder in a day, but color faded and a faint chemical smell hinted at slow breakdown. Sunlight doesn’t do this compound any favors, so I keep it in the dark. Storing it next to acids or oxidizing agents tempts fate—vapors drift and mess with stability. Spacing out storage helps, and a paper log of where chemicals sit in a cabinet avoids expensive mistakes.

Security and Spill Prevention

Access isn’t just about following rules. Unsupervised storage means someone new or less experienced can grab the wrong bottle or store it poorly. Once, a student stacked weights on top of a salt jar and cracked the cap. Setting up rules about returning chemicals immediately after use keeps everyone safer. Secondary containment bins catch small spills and make cleaning up after accidents far less stressful. Nobody wants to spend an afternoon mopping toxic materials from the floor.

Smart Practices for Long-Term Safety

Labeling stands out as a simple but essential step. Reusing an old bottle without scratching off previous labels only leads to confusion. I keep clear labels with full chemical names and date of opening. This avoids mix-ups and signals when the chemical’s shelf life might run out. Regular checks of inventory, caps, and container integrity let small problems be fixed before they get costly or dangerous.

Better Storage, Better Results

Safe storage for Tetramethylammonium chloride isn’t about jumping through hoops or satisfying regulations alone. It’s about protecting a workplace and everyone inside. Taking a bit more time to keep it dry, cool, secure, and away from reactive neighbors avoids emergencies and wasted resources. Experience proves that good habits become second nature, and they pay off every step of the way.

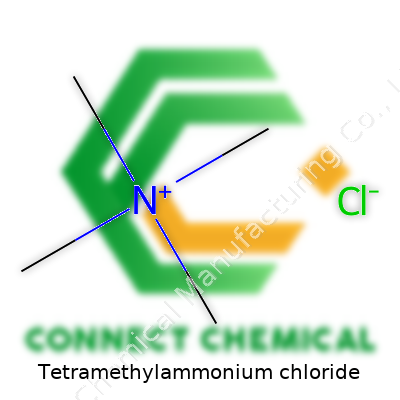

Understanding the Basics

The chemical formula for Tetramethylammonium chloride is (CH3)4NCl. This compound features a nitrogen atom at the center, surrounded by four methyl groups, and balanced out by a chloride ion. On paper, that looks pretty simple. In reality, this structure gives the substance its own unique set of roles, especially in research chemistry and the chemical industry.

Why the Formula Carries Weight

I remember my first encounter with Tetramethylammonium chloride back in undergraduate lab work. The white, crystalline salt didn’t look like much, but breaking down its formula brought a new perspective on quaternary ammonium compounds. The methyl groups bonded to the nitrogen atom mean Tetramethylammonium holds a fixed, permanent positive charge. This quality bumps up its use in everything from organic synthesis to phase transfer catalysis. Not every salt can move between water and organic solvents so effortlessly.

Applications Across the Board

Its formula isn’t just a classroom exercise. Chemical manufacturers lean on Tetramethylammonium chloride as a reagent in several syntheses. For instance, its clear-cut charge distribution helps shuttle ions across boundaries, such as moving reactants from an organic layer into an aqueous one. That means more efficiency in labs and on factory floors.

Its role doesn’t stop there. Researchers sometimes use it as a source of tetramethylammonium ions, valuable for adjusting the ionic strength of solutions. Microbiologists have even explored it as a tool for DNA extraction, as its molecular structure disrupts cell membranes without leaving much residue behind. I’ve seen firsthand how even minor differences in ionic balance, tuned by a salt like this, can turn an experiment’s outcome on its head.

Health and Environmental Considerations

The chemical makeup of Tetramethylammonium chloride brings benefits, but it also requires respect. Like most quaternary ammonium salts, it can disrupt biological activity—useful in disinfection, risky if mishandled. The nitrogen center, stacked with four methyl groups, limits how the molecule breaks down. That means run-off or improper disposal can lead to environmental buildup. Public research points out potential toxicity to aquatic life, which raises stakes for responsible chemical handling. Not all institutions have strong waste management in place, so consistent protocols and community awareness matter if this chemical is anywhere near water supplies.

Safer Practices and Alternatives

For labs and industries, an immediate solution involves double-checking storage and waste practices. A good plan starts with clear labels, secondary containment, and having spill kits on hand. Chemists always benefit from substituting less-toxic compounds where possible, even if it means revisiting old protocols. Digital platforms now list eco-friendlier alternatives for a growing range of applications, often driven by feedback and data from working scientists. It usually comes down to a mix of smart choices and better infrastructure—two things every lab can work toward.

A Formula That Tells a Story

Every chemical formula has a story, and Tetramethylammonium chloride speaks volumes about how chemistry ties molecular structure to real-world action. Its unique arrangement brings convenience and efficiency, and those upsides come with accountability. With good habits and awareness, chemists and manufacturers can keep making useful discoveries without adding unnecessary risk.

Understanding the Substance

Tetramethylammonium chloride may sound like something found only in advanced chemistry labs. Truth is, it pops up in more places than most folks imagine, from industrial processes to some research settings. Over the years, I have watched hazardous materials training grow stricter. The hazards here are real—this compound can be toxic, and sometimes people underestimate it. Its main trick is being a quaternary ammonium salt that’s water-soluble, which means spills can spread quickly on a wet bench or floor.

Recognizing the Hazards

Direct skin or eye contact with tetramethylammonium chloride isn’t just uncomfortable. It can set off burning, redness, or even more severe tissue damage. Inhaling its dust or vapor does a number on the respiratory system—persistent cough, throat irritation, in some cases, dizziness. Swallowing it should never even be on the table; exposure this way can cause vomiting, muscle weakness, and worse, impact your nervous system. A little mistake handling this stuff takes seconds, but the health consequences can be long-term.

Safe Handling Is Everyone’s Job

Working with this chemical means thinking a step ahead every time. Gloves, splash-proof goggles, and lab coats aren’t for show. Even for a quick measurement or transfer, skipping gloves invites risk. Respiratory protection, such as a fitted dust mask, becomes essential in dusty environments. Through experience, I have seen colleagues injured just by rushing through a routine task without proper gear. The small effort of putting on full personal protective equipment (PPE) pays off by keeping skin and lungs out of harm’s way.

Good Ventilation Makes a Difference

Ventilation often gets overlooked, especially in older labs or storage spaces. Proper airflow eats away at the buildup of any airborne particles before they have a chance to bother you. Fume hoods aren’t a luxury; they’re a must. People tend to underestimate the evaporation rate or the dispersal of fine dust until headaches start or odd smells stick around. If in doubt, always handle tetramethylammonium chloride inside a hood.

Storage Habits that Prevent Accidents

I always double-check labels and keep containers sealed tight when not in use. Room temperature storage in a dry spot, away from incompatible chemicals like strong acids or oxidizers, slows down any potential hazards. Poor storage can lead to contamination, or even worse, unintended reactions. Using secondary containment like a plastic tray gives a little extra protection against messy spills.

Honest Reporting, Prompt Responses

No one likes to admit a spill or exposure, but transparency beats regrets. Quick reporting means emergency teams can help before effects become serious. Eyewash stations and safety showers aren’t just part of a checklist—they save vision and skin if used right away. It helps when everyone in the workspace gets real-world training, not just a safety manual and a signature line.

Building a Culture of Safety

Growing up around people who value careful work taught me that safety isn’t about paranoia—it's about respect for chemicals and those sharing the workspace. Staying updated with Material Safety Data Sheets (MSDS) shows me details I need, such as whether a spill kit needs replenishing, or if newer, safer handling tools are available. Taking five minutes before a task to review protocols prevents the sort of accidents that make headlines. Even for veterans, complacency opens doors for mistakes. The goal isn’t just following rules—it’s finishing every day in one piece.